- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps César Cedeño

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps César Cedeño

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

With the Houston Astros having advanced to the League Championship Series for the first time since 2005, it seems only fitting to turn this week’s edition of Card Corner over to one of the best players in the franchise’s history. At one time, César Cedeño was not only one of the game’s five-tool superstar talents, but he had some folks drawing comparisons between him and a couple of Cooperstown legends.

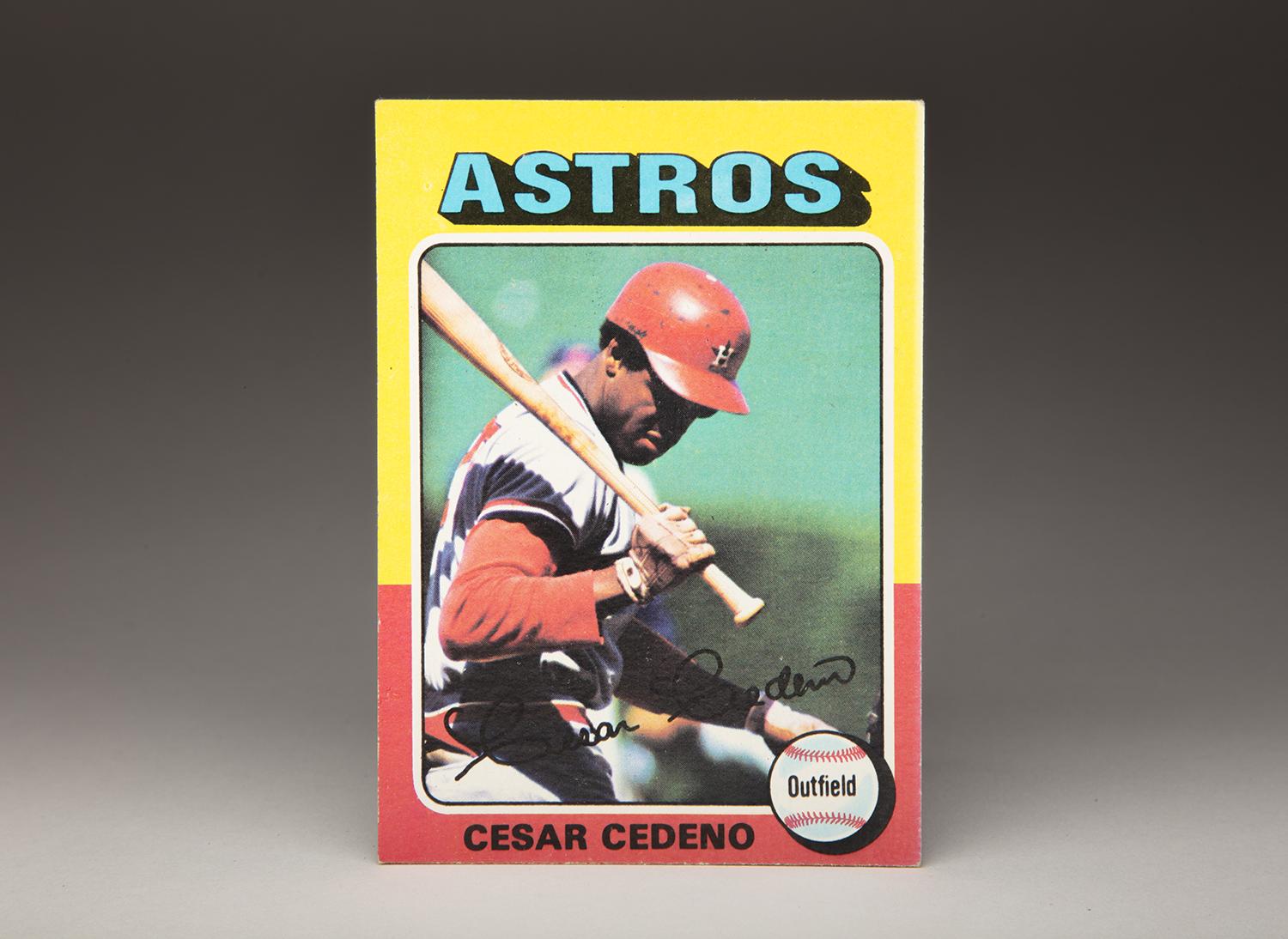

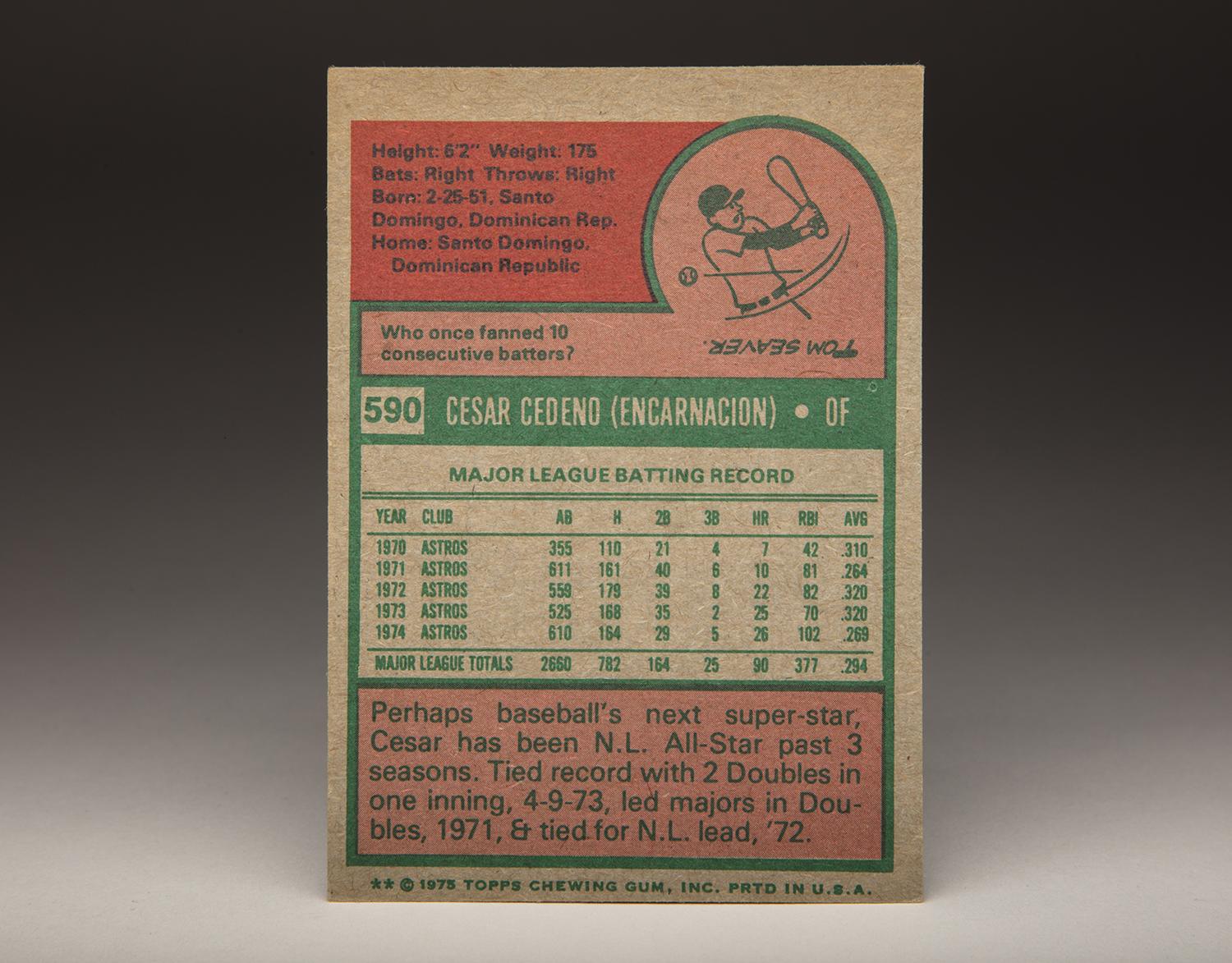

Of all the Cedeño cards that Topps produced, this one is easily my favorite. It’s part of the iconic 1975 set, in which Topps introduced multi-colored borders for the first time in its history. The brightly designed cards became popular with collectors at the time, but they have only increased in appeal since then, especially for those older fans who nostalgically remember the gaudy colors of the psychedelic 1970s. The borders also had an unintended effect over time, making it difficult to find examples of the 1975 set in mint condition; the borders tend to chip and show off any kind of imperfection, much like the black-bordered cards of 1971.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The colored borders, in this case a lively combination of red and yellow that nicely complement the Astros’ uniform colors from 1974, represent the start of my appreciation for the Cedeño card. Topps also gives us an ultra-cool action photograph, but it’s not a typical action shot. Instead, the photographer takes the picture from an angle that we don’t often see on cards: Directly behind home plate. Most of the time, Topps photographers were stationed in camera wells located beyond the first and third base dugouts, explaining why we so often see side shots of hitters and pitchers.

Looking from behind in this case, we see Cedeño stepping into the batter’s box during a sunny afternoon at Wrigley Field – notice the blurred ivy in the background – looking downward as he paws at the dirt with his feet in preparation for his at-bat. Given the clarity of the photo, the sun-splashed afternoon at beloved Wrigley and the unusual angle from which the photographer has done his work, this card becomes a beauty in every way.

By 1975, Cedeño’s talent level was well established. He had been selected to three consecutive All-Star teams, won three straight Gold Glove Awards and received MVP consideration three years running. Even with his batting average dipping to .269 in 1974, Cedeño looked like one of the game’s brightest young talents. Cedeño seemed headed for a long career as an elite center fielder – and potentially a place in Cooperstown.

As a native of the Dominican Republic, Cedeño was not subjected to the amateur draft that baseball had first adopted in 1965. In 1967, the 16-year-old Cedeño was free to negotiate with any of the 20 teams then in existence. In October, Cedeño opted to sign with Astros scout Pat Gillick, who was then near the beginning of his career as a Hall of Fame executive.

Despite being in the midst of his teenaged years, Cedeño moved up quickly within the ranks of the Astros’ system. After only two and a half seasons in the minors, he made his debut for Houston in June of 1970 – at the youthful age of 19. Given his age and his lack of familiarity with American culture – he knew only four words in English at the time of his signing – no one could have blamed Cedeño for being a bit frightened during his rookie season. But his play showed no sign of fear. He batted .310 and stole 17 bases over a 90-game sampling. That performance, accomplished over essentially a half-season, allowed him to finish fourth in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting.

Not only did Cedeño perform well as a rookie, but he also played with a hefty dose of flair and style. He pumped his legs furiously when he ran the bases. He also showed surprising power for a player who was all of 175 pounds. And he threw with fierceness from center field, displaying the kind of throwing arm that most would have associated with a right fielder. All of the above made him one of the game’s most enjoyable players to watch.

As expected, the Astros turned to Cedeño an everyday player in 1971. He played in all but one game, but switched off between the three outfield spots. Perhaps unsettled by the shifting, Cedeño saw his batting average dip to .264.

After the downturn of 1971, César became a full-fledged star in 1972. He hit 22 home runs (an impressive total given the vast dimensions of his home ballpark, the Astrodome), stole 25 bases, posted an OPS of .921 and won the Gold Glove Award for his fielding in center field. His manager, Harry Walker, compared Cedeño to Roberto Clemente, who was in the midst of playing his final season. The comparison was seconded by Astros slugger Lee May, who called Cedeño “a young Clemente.”

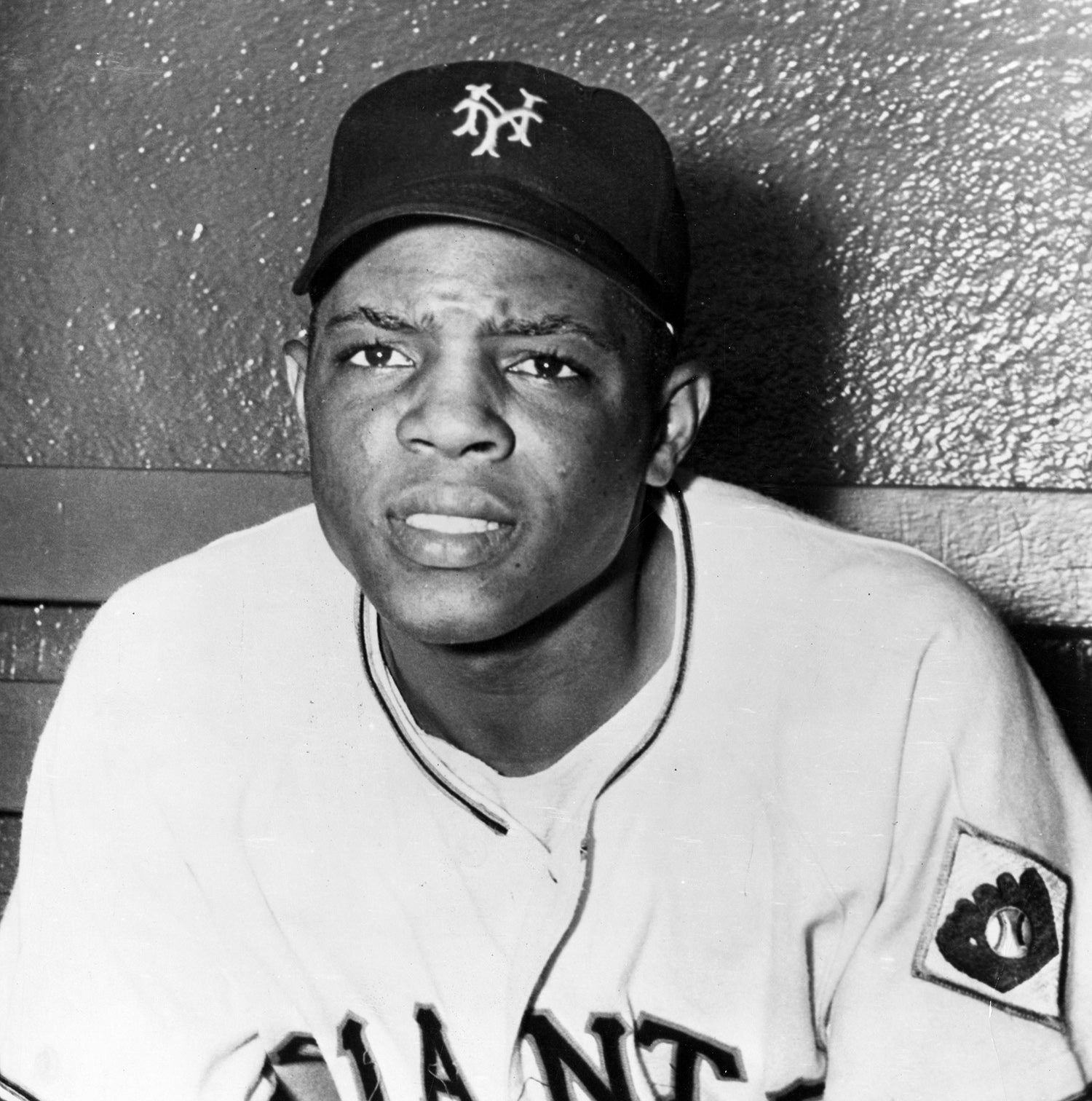

Cedeño did not like the comparison, which he considered an unfair burden, but he enjoyed another banner season in 1973, even if the Astros continued to play like a second-division team. Cedeño played so well, displaying a rare combination of speed, range in the outfield and sheer power, that some Houston writers began to refer to the Astrodome as “César’s Palace.” Cedeño’s all-around excellence – at bat, on the bases, and in center field – evoked comparisons to another one of the game’s legends, but not Clemente. Now the talk involved Willie Mays. Such comparisons to Mays became inevitable because of the identity of Cedeño’s new manager, the venerable Leo Durocher, who had been hired late in 1972.

Cedeño reminded Durocher of Mays, a player whom “Leo the Lip” knew all about, having managed him with the New York Giants for the first half of the 1950s. Durocher loved Mays, whom he regarded as one of his favorite players. He was willing to put Cedeño in the same category. “If I ever saw another Willie Mays, it’s Cedeño,” Durocher told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor. “Of course, Willie has done it much longer. But there’s absolutely no doubt in my mind that Cedeño is going to do it, too… Willie had power in everything – his arm, his bat, his speed; so does this young man.”

Then came the winter, and an incident that was not just controversial, but tragic. Cedeño, married at the time, was with another woman at a motel in his native Dominican Republic. Cedeño had a .38-caliber gun, which the young woman insisted on seeing. She grabbed the gun, which Cedeño then tried to take back. As the two wrestled with the gun, it fired by accident, the bullet hitting the woman in the head and killing her instantly.

Cedeño remained in jail as the police investigated the tragedy. Initially, the police believed that Cedeño had fired the gun and charged him with voluntary manslaughter. But further investigation, including a paraffin test, determined that the woman, and not Cedeño, had fired the deadly shot. The authorities amended the charges, downgrading them to involuntary manslaughter, allowing Cedeño to gain his release from jail after only 20 days. He was forced to pay a fine, but escaped any further punishment.

Perhaps affected by the tragic incident, Cedeño saw his OPS fall to .799 in 1974, a decline of more than 100 percentage points. The season was made more difficult when he received a death threat to his hotel room in Pittsburgh, allegedly in retaliation for the incident in which his girlfriend had died. Cedeño would bounce back with better seasons in 1975 and ’76, remaining one of the most dynamic players in the National League, but would never quite attain the heights of his earliest seasons.

Cedeño claimed that the horrible incident had no effect on his playing career, but others believed that there was a cause and effect. No less than an authority than Peter Gammons, one of the game’s top writers and a winner of the Spink Award, wrote a 1977 article for Sports Illustrated that indicated the tragedy had affected Cedeño’s on-field game. “He’ll end up with decent statistics,” an unnamed Astro told Gammons, “but statistics are for people who don’t know anything. He’s never been the same hitter since that incident.” Later in his career, a fan in Atlanta would taunt Cedeño by calling him “killer.” Cedeño responded by jumping into the stands and scuffling with the fan.

From a pure baseball perspective, it didn’t help matters that the Astros moved their fences back even further in 1977, making home runs the rarest of occurrences at the Astrodome and frustrating a power hitter like Cedeño. Injuries to his knees and ankles also took their toll, robbing Cedeño of some of his speed. The onslaught of injuries and illness only worsened the next two seasons. In 1978, he tore a ligament in his knee, cutting short his season by half. In 1979, he endured a bout with hepatitis, which resulted in him losing nearly 15 pounds and sapping him of his usual strength.

In 1980, Cedeño bounced back to hit .308 and finish 13th in the National League MVP balloting. In some ways, that was his last hurrah as an Astro. During the strike-shortened season of 1981, the Astros moved him to first base, a concession to the chronic ankle problems that had plagued him. After the season, the Astros shopped their veteran star, who was now 30. At the winter meetings, the Astros struck a deal with the Cincinnati Reds, who were willing to give up a young Ray Knight in a one-for-one swap.

After the trade, a few of Cedeño’s teammates anonymously criticized him. One player cited Cedeño for a supposed lack of clutch hitting. Another said he was constantly injured. Cedeño responded by saying that the ex-teammates were simply jealous. For the most part, he shrugged off the criticism and became a solid role player for the next three-and-a-half seasons. Playing mostly as a right fielder and first baseman, he sandwiched two good years around a bad one, before he slumped significantly in 1985.

In late August of ‘85, the Reds practically gave him away to the St. Louis Cardinals, who surrendered only a minor league outfielder. The Cardinals, who were in the midst of a drive to win the National League East, needed help at first base, where Jack Clark was hobbled by injury. Cedeño proceeded to go on one of the most incredible tears the game has ever seen from a late-season acquisition. Cedeño batted .434 and put up an OPS of 1.213 in 82 plate appearances, helping the Cardinals wrap up the Eastern Division title.

Cedeño’s performance drew everlasting appreciation from his manager in St. Louis, Whitey Herzog. Twelve years later, in an interview with the Sporting News, Herzog remembered Cedeño as the difference-maker in winning the division. “When Cedeno was with us, he played like hell, like he was out to prove the world wrong,” Herzog recalled. “It was amazing. I never really saw anything like it.” Along with players like Donn Clendenon and David Justice, Cedeño became one of the most important midseason acquisitions in baseball history.

With Clark set to return in 1986, the Cardinals allowed Cedeño to enter free agency. He signed with Toronto, where only days after being told he would make the team as the fourth outfielder he was given his unconditional release. He then found work with the Los Angeles Dodgers, where he batted .231 before being released in midseason. Cedeño signed a minor league deal with St. Louis, but was unable to make his way back to the major leagues.

César called it quits, though he did attempt a comeback with the Astros in the spring of 1989, only to be released just before Opening Day. He remained active in the game, serving as a coach in the systems of the Astros and Washington Nationals, and managing to curb the temper that he so often displayed as a ballplayer. This past summer, Cedeño worked as the hitting coach for the Greeneville Astros, completing his 38th season in the game and his 30th with the Astros’ organization.

Even when Cedeño retires, he will always be associated with the Astros, where his first few seasons made him a 1970s version of Mike Trout. Long before there was Jose Altuve and Carlos Correa and George Springer, César Cedeño fueled the franchise and made Houston the home of César’s Palace.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

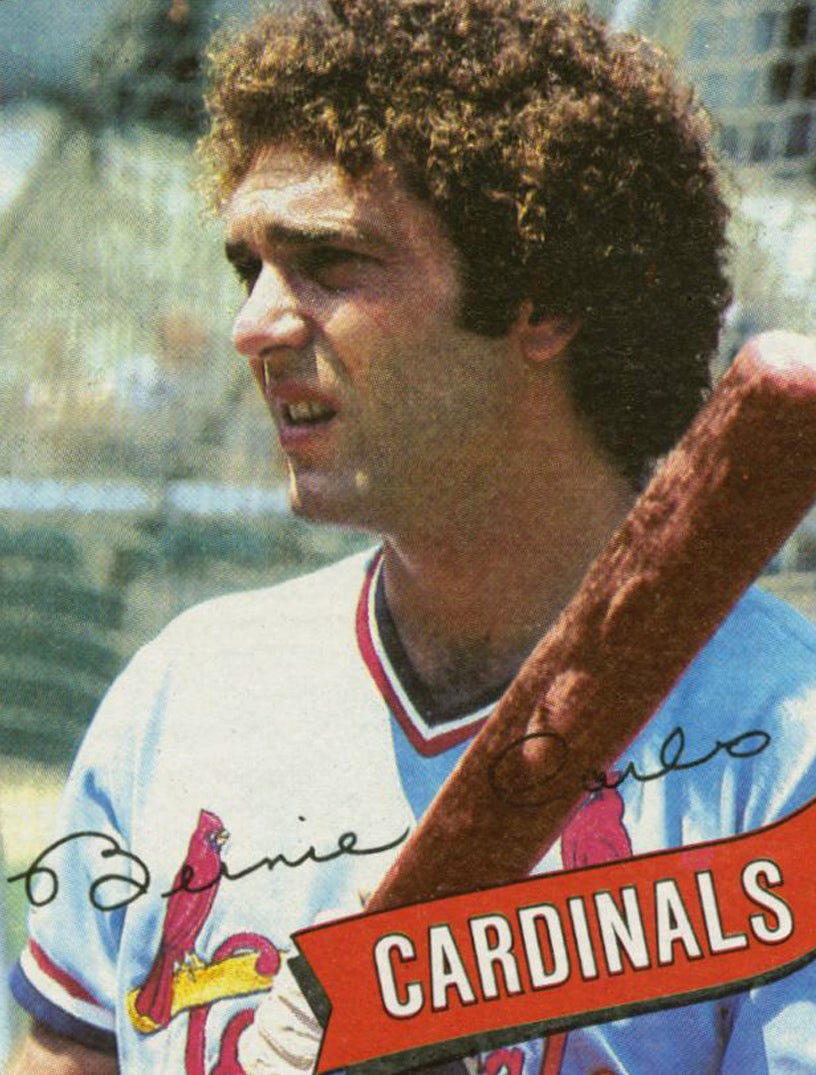

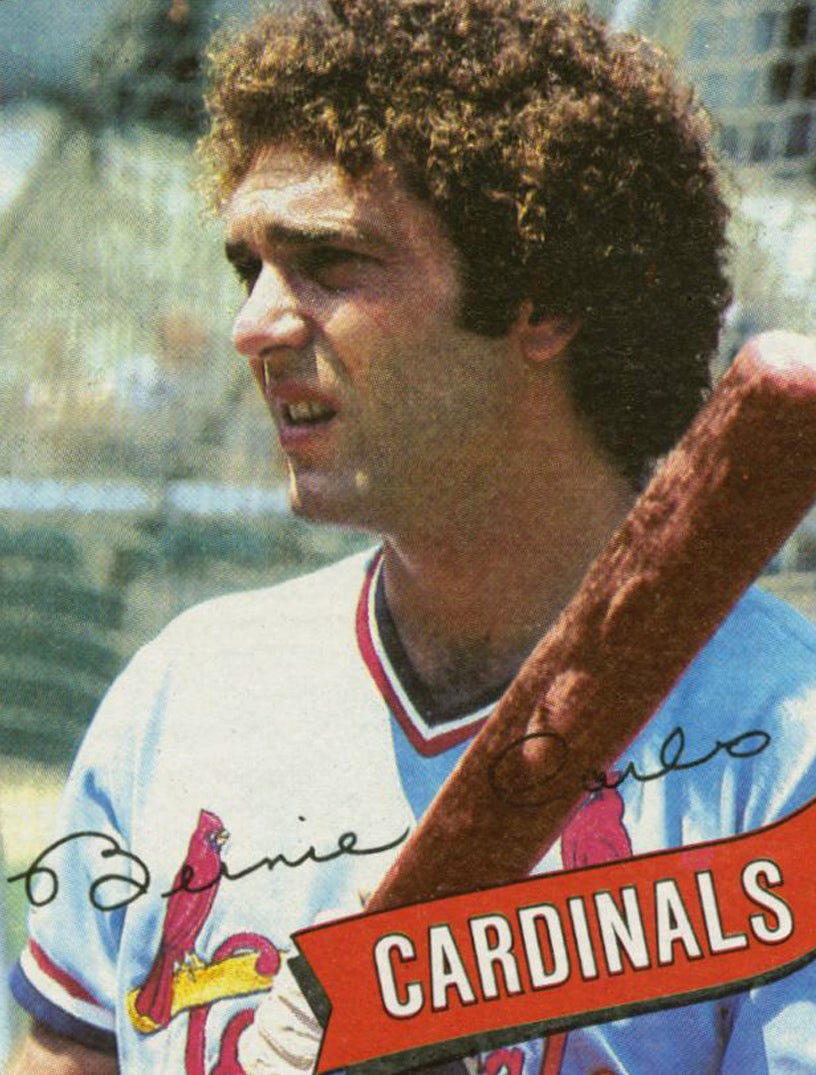

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

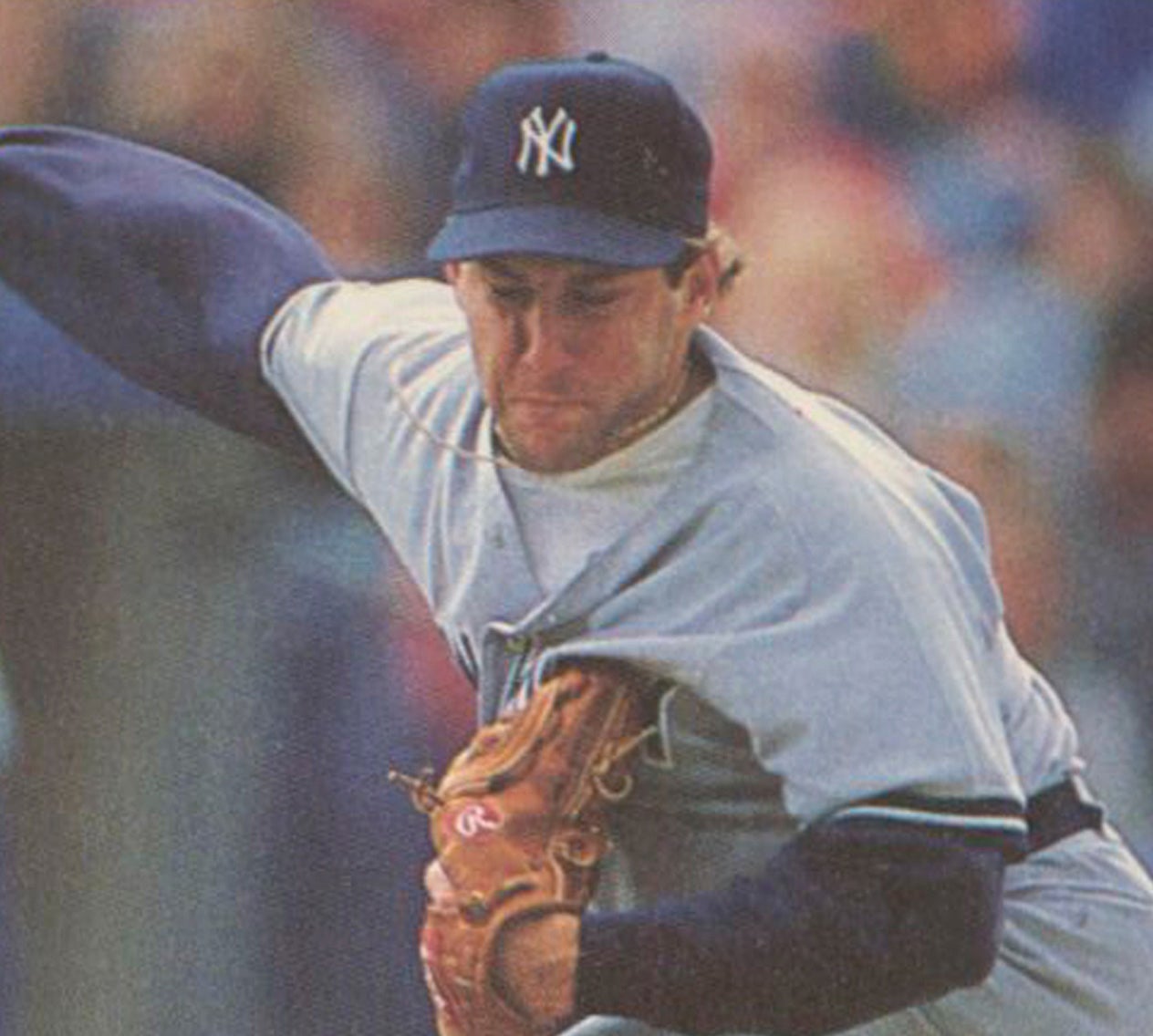

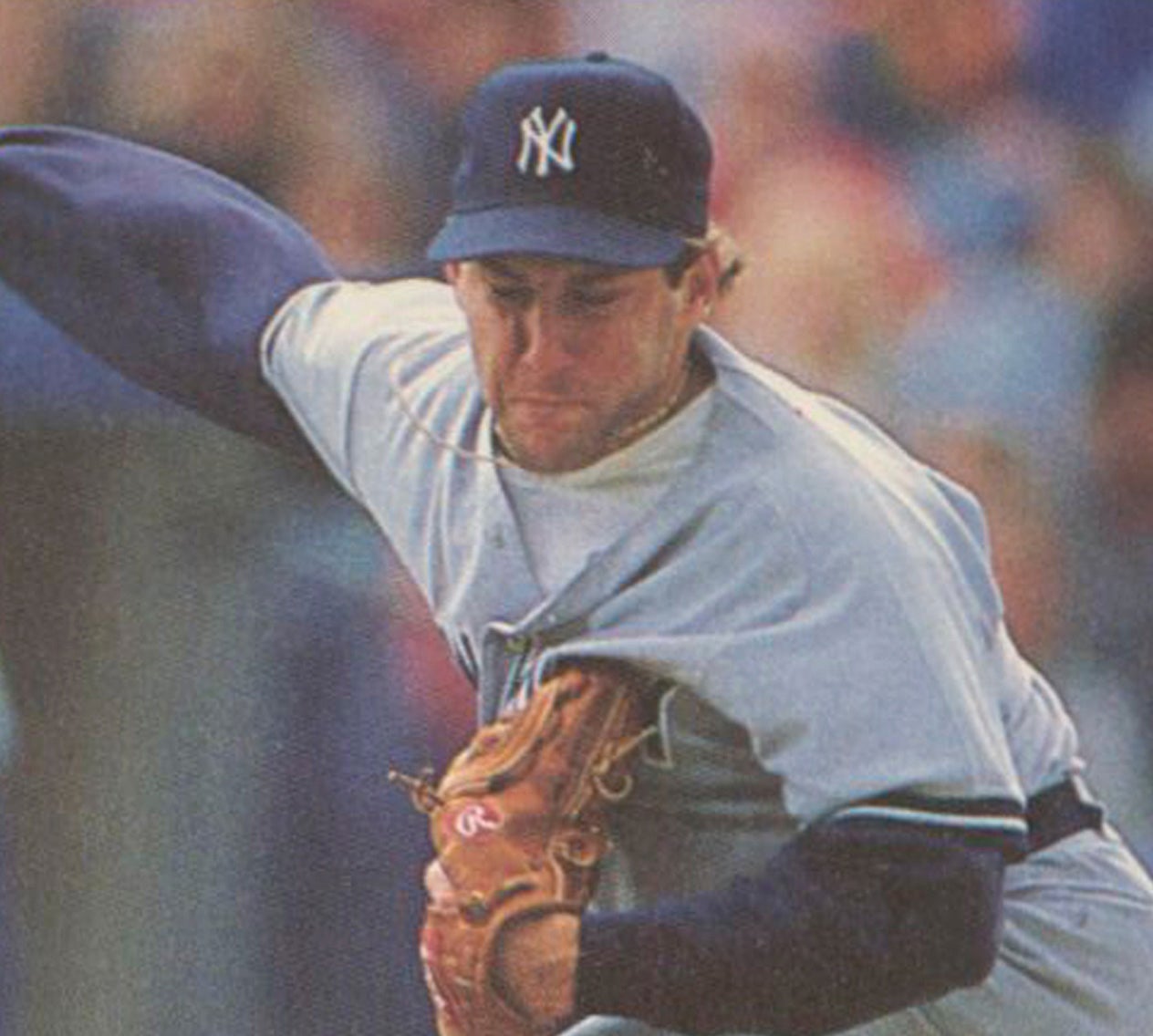

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

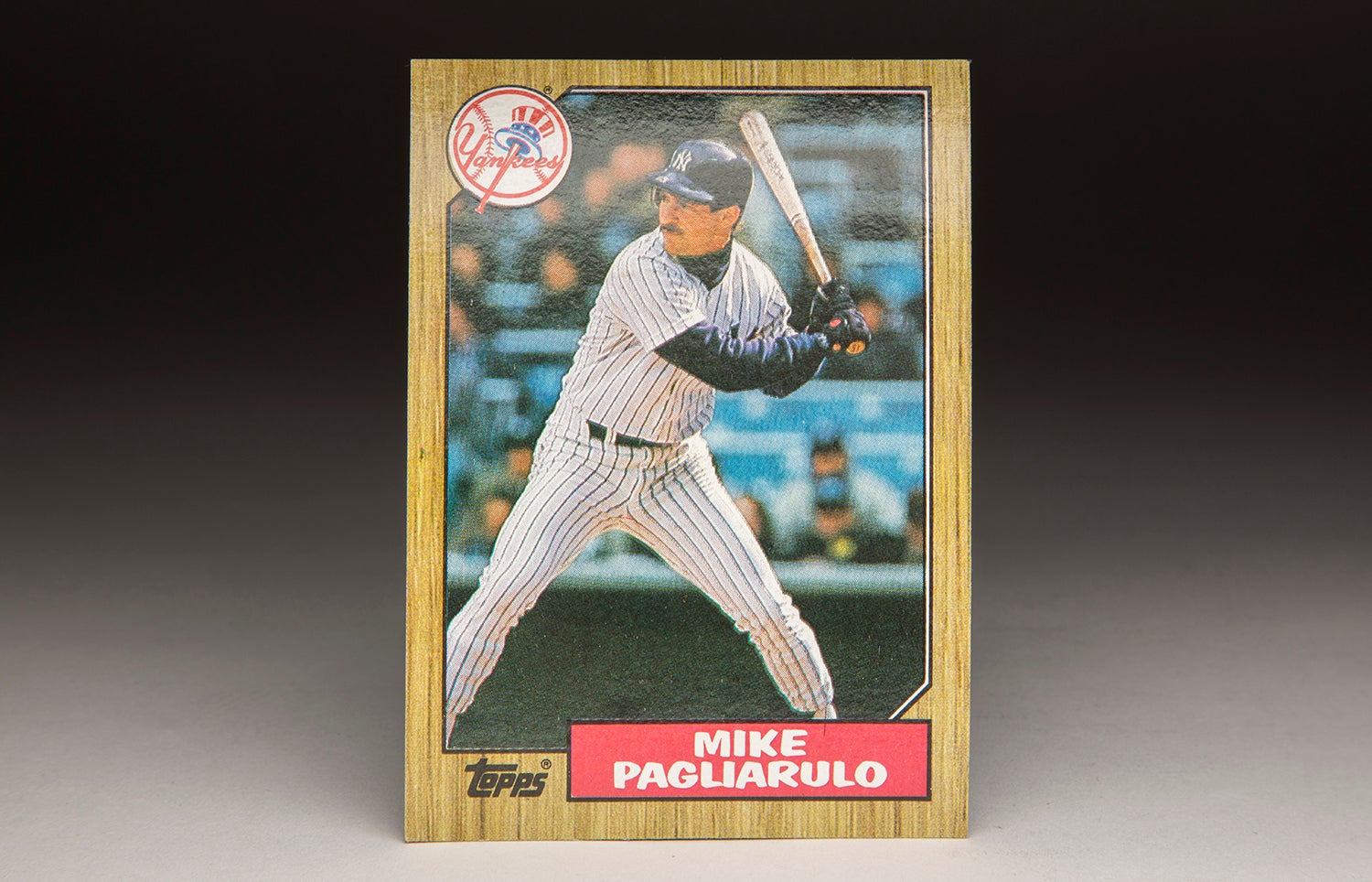

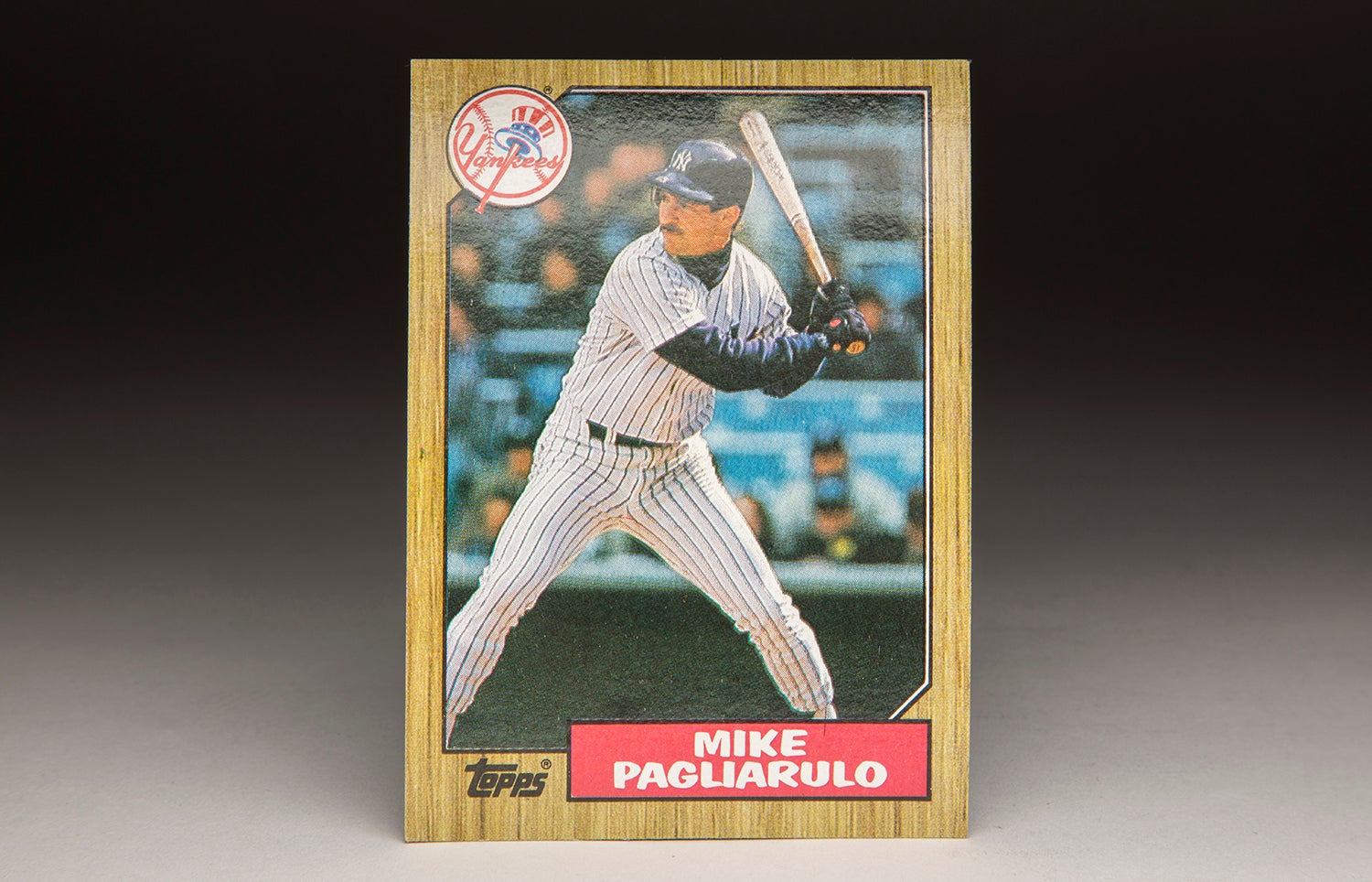

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Pagliarulo

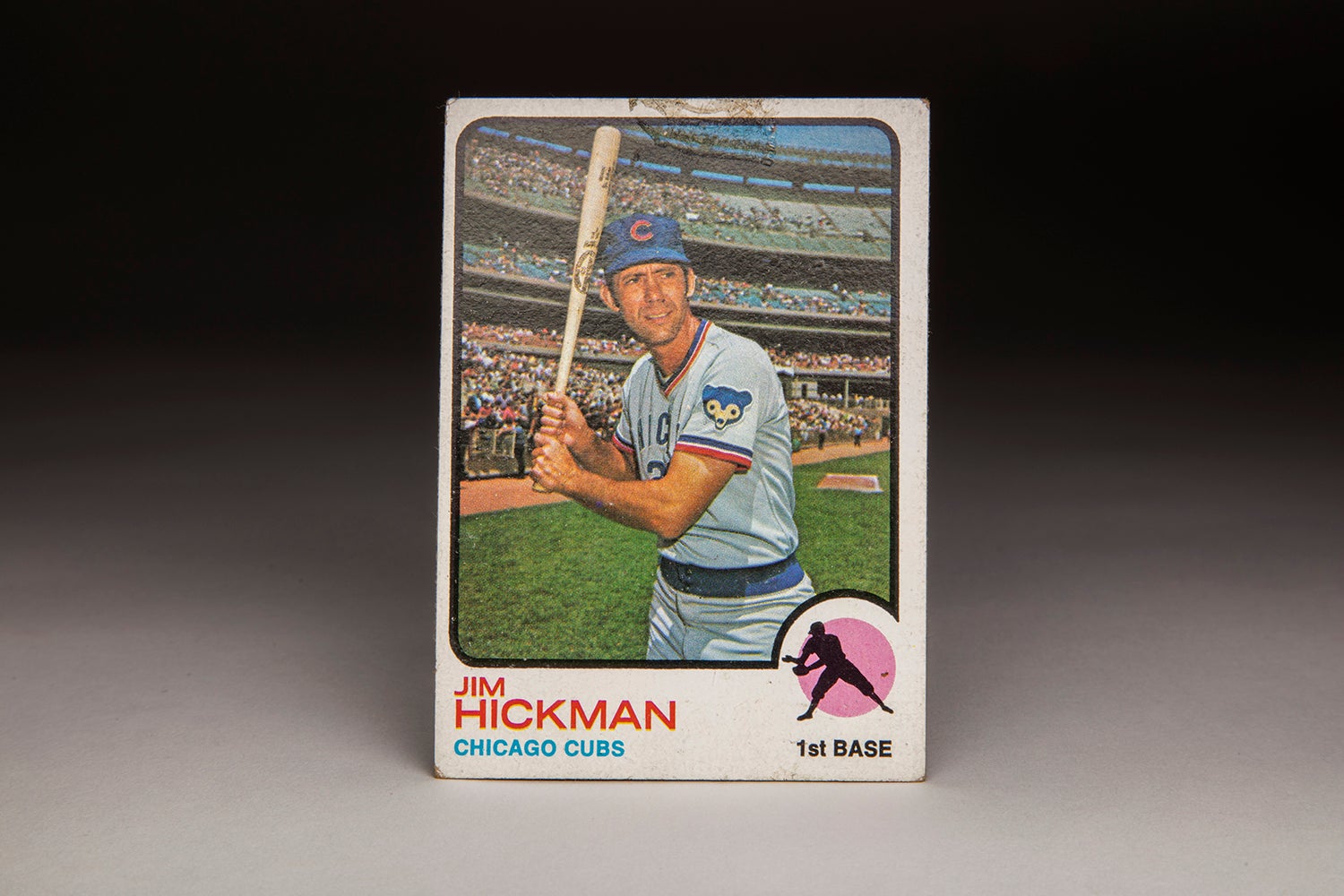

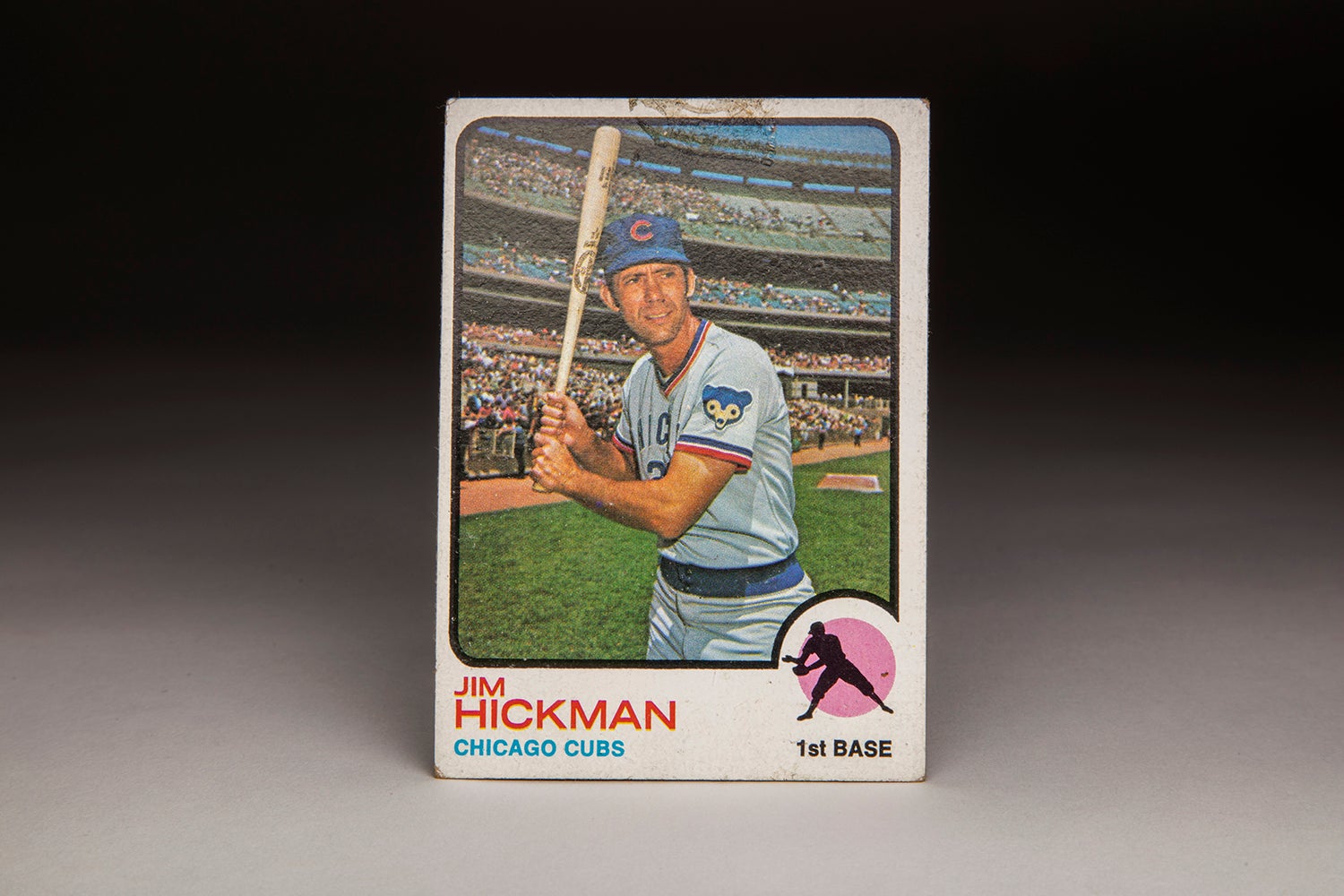

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Pagliarulo