- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Tommie Agee

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Tommie Agee

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

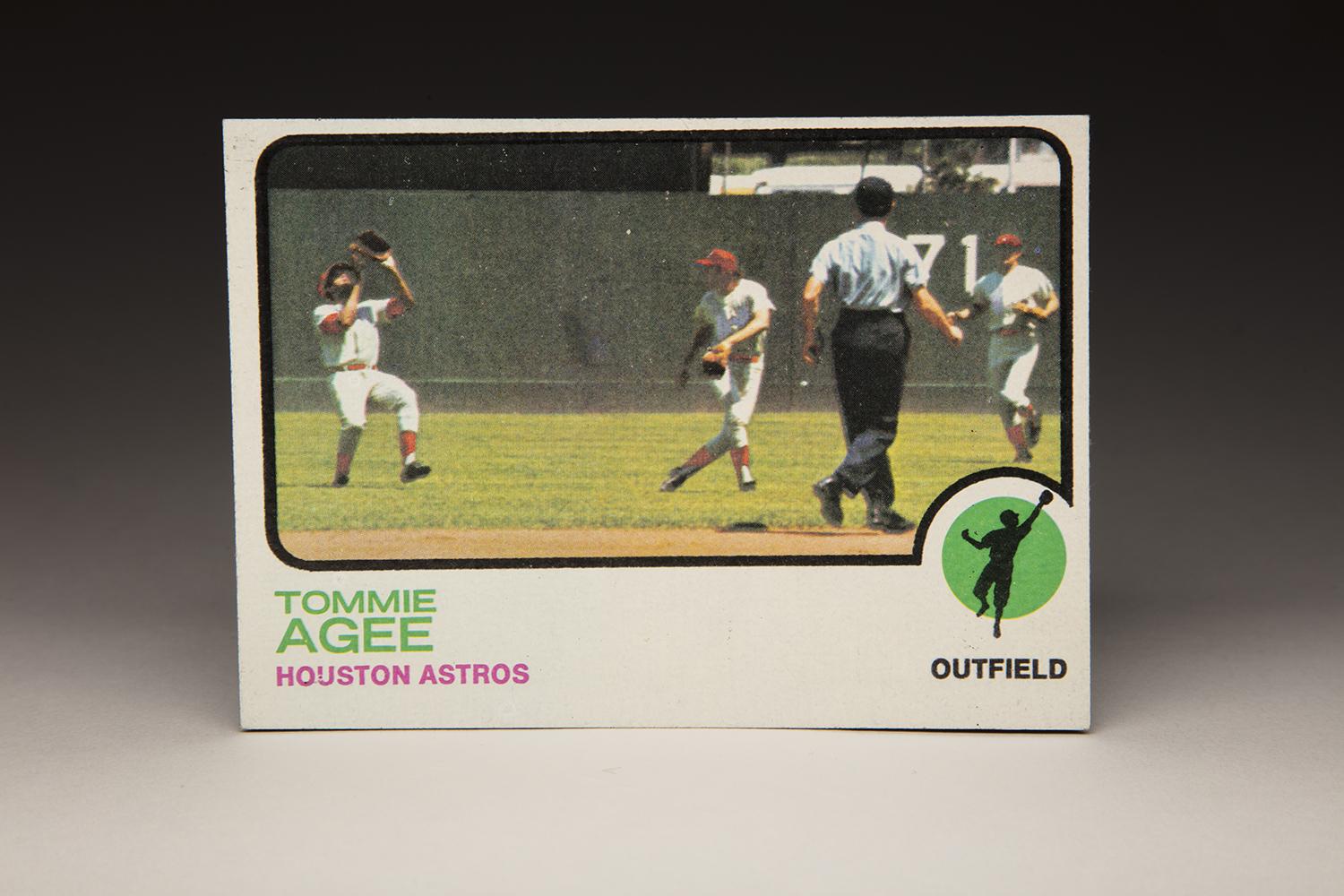

For collectors my age (and older), the 1973 Topps set holds a special place of fondness. The set’s emphasis on action photography, its simple design and its iconic use of a silhouetted figure in designating a player’s position make it appealing to many collectors and fans.

After achieving so much success with action shots in its 1971 and ’72 sets, Topps went whole hog with action in ’73. With their photographers used to snapping action photos at the ballpark, Topps tried to include as many action shots as possible. This led to some overzealousness on the part of Topps, to the point that the company included too many action shots taken from unusual angles and long distances. The set contains some bizarre choices.

For example, the card of Steve Garvey, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ up-and-coming star, actually provides us a better view of his teammate, Wes Parker. And a card for Chicago White Sox infielder Luis Alvarado shows us two infielders, but it’s not clear at first glance which player is Alvarado. Furthermore, the photo gives us a view of a parking lot in the background, an unusual backdrop for a baseball photo. For fans of vintage automobiles from the early 1970s, the Alvarado card is a special treat.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

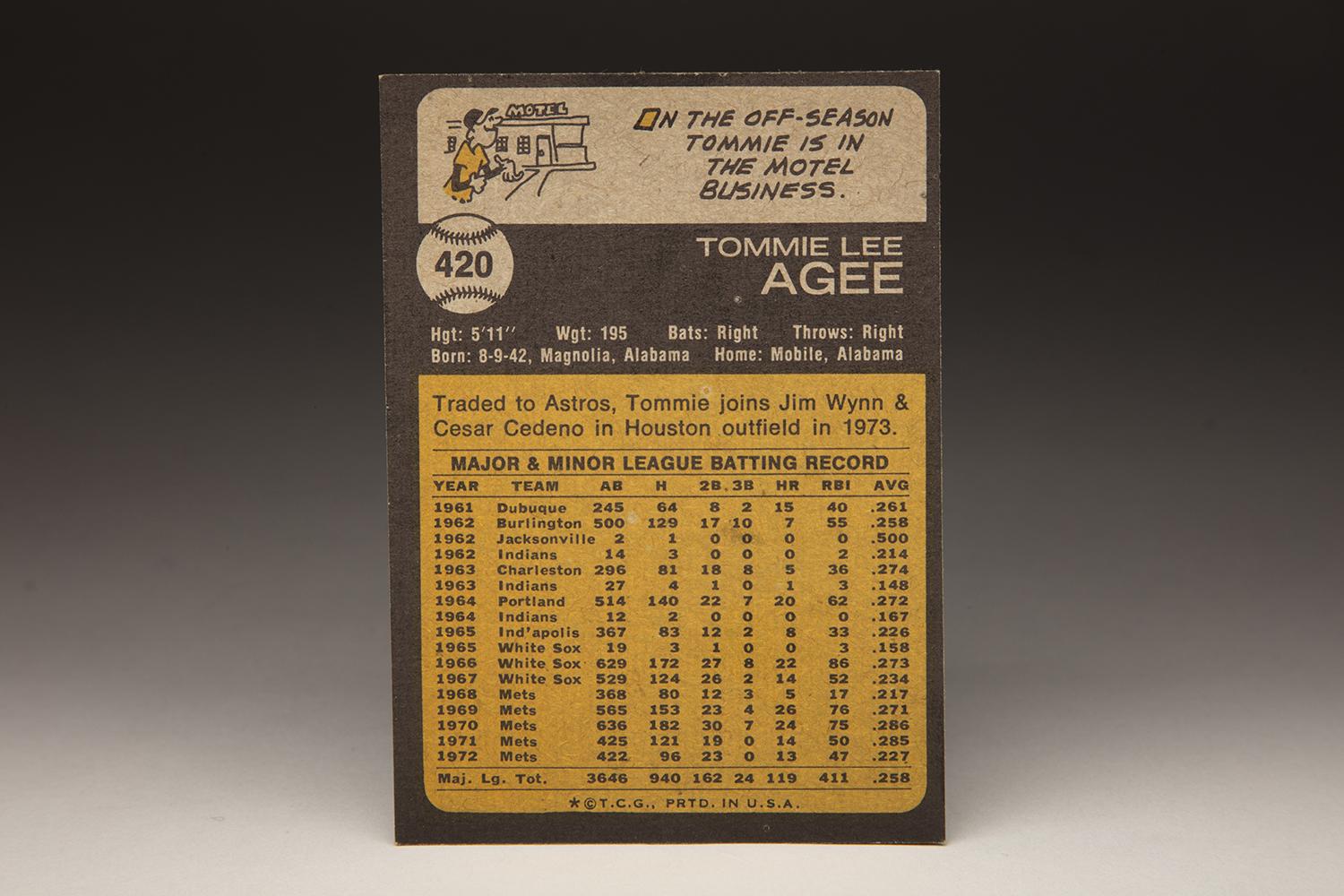

One of the most bizarre but nonetheless intriguing cards from the set is Tommie Agee’s card, which is presented in a landscape (or horizontal) format. (The landscape look was used rather liberally in 1973.) Agee is not exactly centered on the card; he is seen on the far left, camping under a short fly ball during a 1972 game at Shea Stadium, where the 371-foot sign is visible in right field. Agee’s figure, which appears rather small on the card, shares the photo with two other players, Ken Boswell and Rusty Staub.

All three players can be seen wearing the airbrushed colors of the Houston Astros, Agee’s team in 1973. But before being touched up, the photo actually showed the players wearing the colors of the New York Mets. Agree played for the Mets in 1972, before being sent to the Astros in a wintertime deal. Boswell and Staub also sport the Astros airbrushed colors (which actually resemble the colors of the Cincinnati Reds), even though these two players would remain with the Mets in 1973.

Here’s what’s somewhat ironic about Staub’s appearance on the Agee card: Staub did not otherwise appear in the 1973 set. There was no card for him at all, because he refused to sign a contract with Topps that season. In fact, Staub held out in 1972, as well. It was not until 1974 that Staub and Topps would come to an agreement, allowing the Mets’ star to regain his place on cardboard.

Given the distance from which the cameraman took this shot, it’s difficult to tell that it’s actually Staub running in from right field. But it is. In later years, higher speed cameras with the ability to zoom in from greater distances would have done far better work in showing Agee (and the other players) in action. But in the early 1970s, professional photographs had to work within the limits of available technology. So Topps settled for a shot that was something less than ideal, just so that it could include as much action as possible in its set. And as young collectors, we didn’t care that the photo lacked professional quality. We just thought that the Agee action card, and others like it, were cool. And some of us still do.

For Agee, the 1973 card was one of the later ones of his career. His professional career began 12 years earlier, when he signed with the Cleveland Indians in the days before the adoption of the MLB Draft. Agee received a signing bonus of $60,000, which was very good money for 1961. The Indians assigned him to Class D Dubuque, where he spent the entire season, hitting 15 home runs in 64 games. The following year, Agee moved up to Class B Burlington; he struggled there, hitting only seven home runs and striking out 128 times in 128 games. Despite the failures, the Indians moved him up to Triple-A for a pair of games and then summoned him to Cleveland in September. He was all of 20, and came to bat 14 times for the Indians, picking up his first two major league hits.

That late-season appearance in Cleveland marked the start of a pattern for Agee. For the next three years, he spent the majority of the summer in the minor leagues, before receiving a cup of coffee in Cleveland. The pattern continued even after the Indians gave up on Agee, trading him after the 1965 season. The Indians sent Agee and left-hander Tommy John to the White Sox as part of a complicated, three-way deal that involved the Kansas City Athletics and brought Rocky Colavito back to Cleveland.

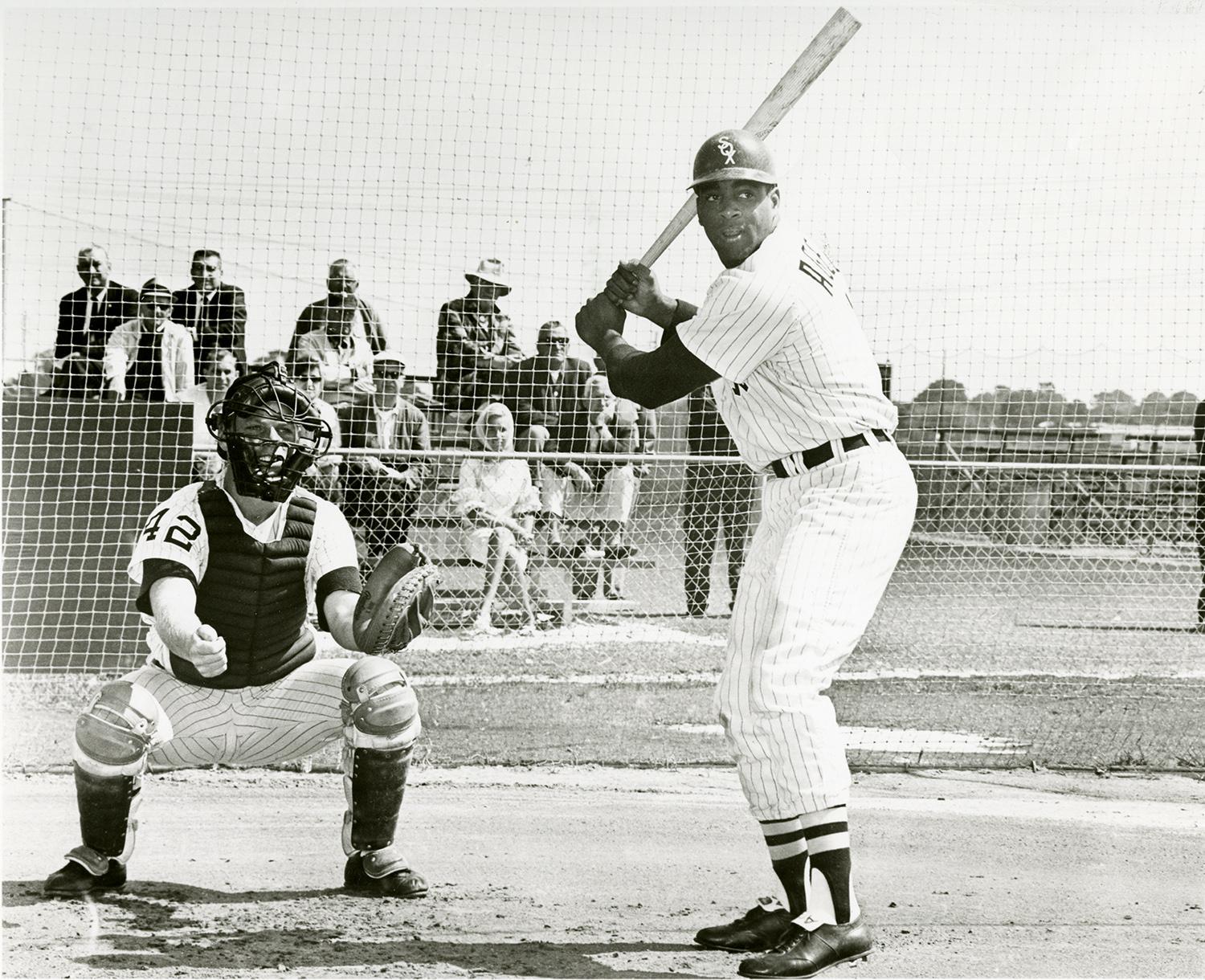

Colavito was a popular figure in Cleveland, but the Indians would come to regret the trade. After a poor season at Triple-A Indianapolis in 1965, Agee still remained in good graces with the White Sox, promoting him to the majors and making him a starting outfielder in 1966. Although Agee was built like a fireplug, at 5-foot-11 and nearly 200 pounds, he could run and cover ground like few others. The White Sox liked Agee so much that they made him their center fielder, bumping Ken Berry, a skilled defensive outfielder, to left field.

Agee took full advantage of his new opportunity. On Opening Day, he hit a memorable home run against tough right-hander Dean Chance. That was a sign of good things to come. For the season, Agee would hit 23 home runs and steal 44 bases, becoming the first 20/20 player in White Sox history. Defensively, he earned Gold Glove Award honors. Most impressively, he won the Rookie of the Year Award, garnering all 16 first-place votes and beating out an impressive class that included Baltimore’s Dave Johnson and Boston’s George Scott. Additionally, Agee placed eighth in the MVP race.

In his first full season, Agee displayed only one flaw: A tendency to swing and miss. He struck out 127 times, a high total for the era. He was vulnerable to right-hand pitchers with good curveballs or sliders.

In 1967, Agee enjoyed a solid first half of the season, good enough to earn selection to the All-Star team. But after the break, he fell into a deep slump. He hit only four home runs, as pitchers took advantage of his struggles against breaking balls. His strikeout rate rose considerably, while his batting average fell to .234. Even his power dropped, as his slugging percentage fell to .371.

The Sox might have chalked up the bad season to the sophomore jinx, but they were concerned that pitchers may have found a fatal flaw in his game. After the season, the Sox made a trade, sending Agee and utility infielder Al Weis to the Mets for a package of four players, including the Mets’ best hitter in Tommy Davis and veteran right-hander Jack Fisher.

It’s not well known, but the White Sox nearly dealt Agee to another team, in a deal that would have created reverberations throughout the game. The White Sox engaged in serious talks with the Boston Red Sox about their star outfielder Carl Yastrzemski. The teams reportedly came close to completing the blockbuster one-for-one trade, but Sox owner Tom Yawkey wisely balked at the last minute.

Agee might have enjoyed playing half of his games at Fenway Park, but he was happy about the trade to the Mets. It allowed for a reunion with boyhood friend Cleon Jones, the Mets’ left fielder. Jones and Agee had been close friends while growing up in Mobile, Ala. In fact, Jones and Agee had been born only five days apart.

As much as Agee looked forward to playing with Jones, his first Spring Training with the Mets brought him only heartache. Playing in the first Grapefruit League game of the season, Agee stepped in against Bob Gibson, who tossed an errant fastball that hit Agee in the back of the head. The beanball left Agree dazed and continued to bother him throughout the coming season.

Mets manager Gil Hodges loved Agee’s combination of speed and power and made him his leadoff man. Despite the show of confidence from his skipper, Agee flailed away during the early season. In the Year of the Pitcher, Agee struggled more than most hitters. In April, he went through an 0-for-34 stretch. For the season, he batted .217, struck out 103 times, and drew 15 walks. He hit only five home runs. His OPS of .562 looked like that of a utility infielder.

With two straight bad seasons in a row, the Mets could have given up on Agee. To their credit, they did not. Hodges retained faith in Agee, keeping him in center field and in the leadoff slot.

The manager’s confidence paid off. In early April of 1969, Agee became the only player to hit a home run into Shea Stadium’s upper deck; the ball traveled an estimated 480 feet. For Agee, it was one of 26 home runs that season. Defensively, he tackled the challenge of center field at Shea Stadium, always difficult to play because of the wind currents and the lengthy dimensions.

All things considered, Agee emerged as the best all-around position player on the division-winning Mets. As Hodges told the San Diego Union-Tribune in late August, “If I had to pick out one man who’s responsible for our rise, I guess it would have to be Agee.” Fellow Mets outfielder Art Shamsky concurred. “Agee has to be the single biggest reason for our success this year.”

After winning the National League East and disposing of Atlanta in the Championship Series, the Mets advanced to the World Series, where Agee’s performance only rose higher. With the Series tied at a game apiece, the Mets and Baltimore Orioles prepared for a critical Game 3. Right from the start, Agee supplied some offensive heroics. Leading off the bottom of the first, he blasted a home run to center field, victimizing one of the game’s best pitchers, Jim Palmer.

Mets fans would soon come to forget the home run, if only because of what Agee would do in the field. In the fourth inning, with runners at first and second, Elrod Hendricks laced a ball deep toward left-center field, for what seemed like a certain run-scoring double. Shading Hendricks toward right field, Agee ran an estimated 40 yards across center field, made a backhanded stab of the ball, and snared it in the edge of his glove. Agee not only robbed Hendricks of a double, but saved two runs from scoring.

In the top of the seventh, Agee did it again. The Orioles loaded the bases with two outs, bringing Paul Blair to the plate. Blair slashed a line drive toward right-center field, the ball seemingly ticketed for a two-base hit. Unleashing a full sprint, Agee caught up to the ball and then made a headlong drive, snaring the ball before it landed on the warning track. This time he saved three runs from being scored.

After the game, reporters cornered Agee and asked him about the two remarkable catches. “The first one was harder,” Agee told the Sporting News. “Because I had to reach across my body and catch it backhanded. I thought I had the second one all the way, but the wind caught it and it dipped suddenly, so I had to dive for it.” For his part, Hodges thought the second catch was the greatest play he had ever seen in the World Series. At the very least, Agee’s catches deserved mentions with some of the greatest plays in Series history, including Al Gionfriddo’s catch in 1947, Willie Mays’ back-to-the-infield grab in 1954 and the Sandy Amoros catch of 1955.

Spearheaded by Agee’s two phenomenal catches (and his leadoff home run), the Mets won Game 3. Sports Illustrated called it “the most spectacular World Series game that any center fielder has ever enjoyed.” Two games later, Agee and the Mets were world champions. Not long after, the city of Mobile honored Agee and Cleon Jones with a downtown parade.

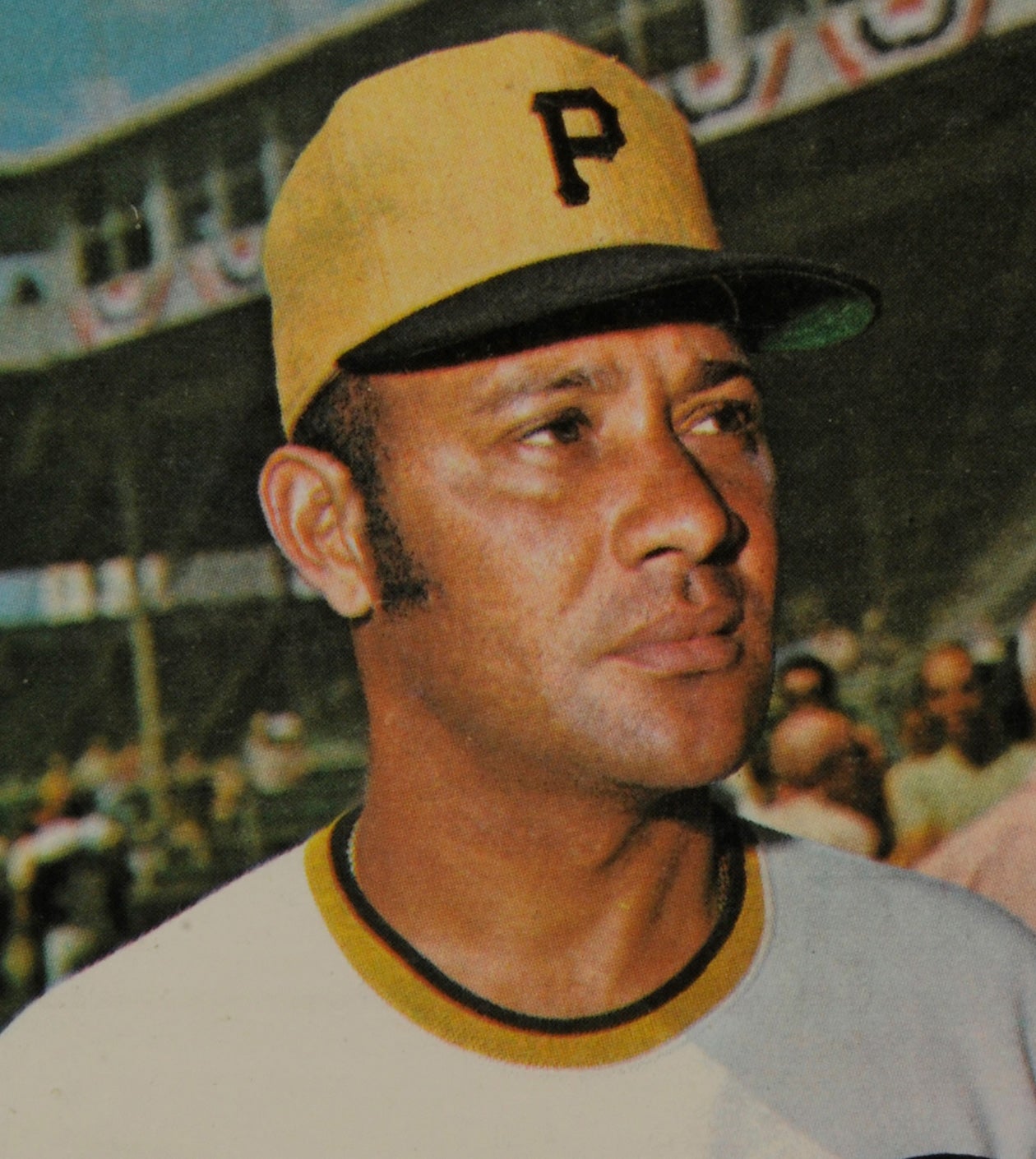

Rusty Staub makes an appearance on Tommie Agee's 1973 Topps card, but Staub did not otherwise appear in the 1973 set. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

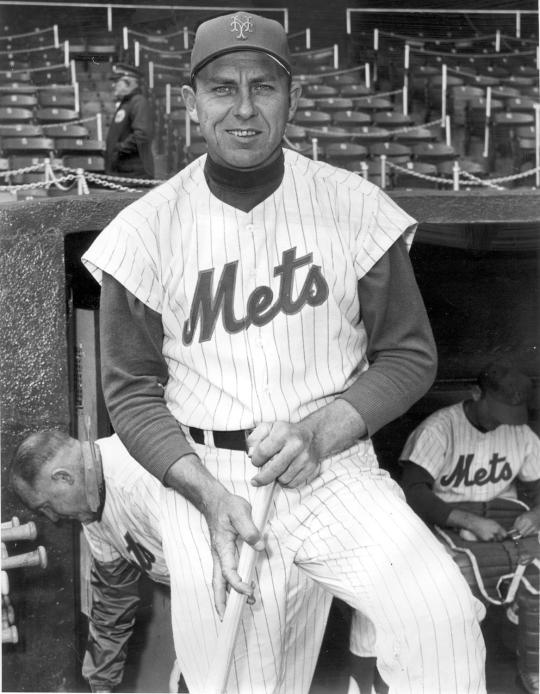

Mets manager Gil Hodges loved Tommie Agee’s combination of speed and power and made him his leadoff man in 1968. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

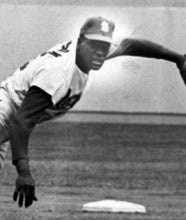

Pedro Borbon earned the nickname "Dracula" when he took a bite out of a hat belonging to Cleon Jones (pictured above), leaving a sizable hole in it. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

In 1970, Agee hit even better, albeit without the World Series glory, compiling a career-best .286 average and an OPS of .812. His season included a 26-game hitting streak. He also stole 31 bases and won his second Gold Glove Award.

At 28 years old, Agee appeared to be in his prime. Then came an injury-plagued 1971 season. A knee injury limited him to 113 games and restricted his power. But he still hit .285 and stole 28 bases. In 1972, a series of events affected the Mets – and Agee. Tragically, Hodges died just before the start of the strike-delayed season. Then Agee came down with a strained muscle in his rib cage, which bothered his swing. And then the Mets acquired Willie Mays in a summer trade with San Francisco. Mays’ presence cut into Agee’s playing time. By season’s end, Agee had a batting average of only .227 and a slugging percentage below .400.

Although Agee was only two years removed from his career-best season of 1970, the Mets worried that his declining performance would continue. They had other concerns, too. There were rumors, unsubstantiated but still whispered, that the Mets felt Agee and Cleon Jones bad become so close as to create a clique within the clubhouse. After the ’72 season, the Mets began to shop Agee to other teams.

One trade rumor had Agee headed to the Chicago Cubs. General manager Bob Scheffing proposed a blockbuster seven-player deal that would have sent Agee, pitchers Gary Gentry and Danny Frisella, and another player to the Cubs for center fielder Rick Monday, right-hander Bill Hands, and an unknown third player. Scheffing wanted to make the deal, but Cubs manager Whitey Lockman told his front office to reject the trade. So the Cubs turned down the proposal, negating the possibility of Agee returning to Chicago, his first major league city.

Scheffing instead made a trade with Houston, sending Agee to the Astros for outfielder Rich Chiles and pitching prospect Buddy Harris. The trade was not well received in New York, where Mets fans wondered why the team received so little in exchange for their popular center fielder.

Agee struggled in Houston, where he found the Astrodome an even more difficult hitting environment than Shea Stadium. Over the first half of the season, Agee showed some power, but other aspects of his game fell off. With his batting average at .234 and his slugging percentage below .400, the Astros felt that Agee was done. On Aug. 18, they sent him to St. Louis for infielder Dave Campbell.

Agee did little for the Cardinals over the final six weeks of the season. In 26 games, he hit three home runs and batted .177, ending the season on the bench. At the winter meetings, the Cardinals parted ways by dealing him to the Los Angeles Dodgers for veteran reliever Pete Richert.

Although Topps printed a 1974 traded card that showed Agee wearing Dodger Blue, he never appeared in a regular season game for the franchise. In late March, during the latter days of Spring Training, the Dodgers released Agee. He was still only 31, but no other major league team showed interest. Rather than prolong his career in the minor leagues or the Japanese Leagues, Agee decided to retire.

Leaving baseball, Agee pursued other interests. Still, he remained popular with his ex-teammates, and with fans who recalled the era of the “Miracle Mets.” He kept in touch with the fan base by holding instructional clinics for children. He ran an annual charity golf tournament in his native Mobile. He also appeared in a 1999 episode of the popular comedy, Everybody Loves Raymond, where he played himself.

Yet, there was more to Agee than just baseball. A smart businessman, he opened up a bar, “The Outfielder’s Lounge,” which was located near Shea Stadium. He also became an executive with an insurance company. While Agee remained successful, his health suffered, largely because of weight problems and a heart condition.

In January of 2001, Agee was leaving his New York City office when he experienced chest pain and then collapsed. Suffering a massive heart attack, Agee was rushed to Bellevue Hospital, where he died soon after. Agee was only 58, which made the news all the more difficult for Mets fans.

It’s now been 17 years since Agee passed. Whenever I hear his name, I think of the day when I heard the news that he died. But a few good thoughts come to mind, too. First, I remember those miraculous catches in the 1969 World Series. And of course, I think of that strange and surreal baseball card in which Topps airbrushed everybody in sight as part of its new quest for action.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Jerry Grote

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Jerry Grote

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick