- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps George Foster

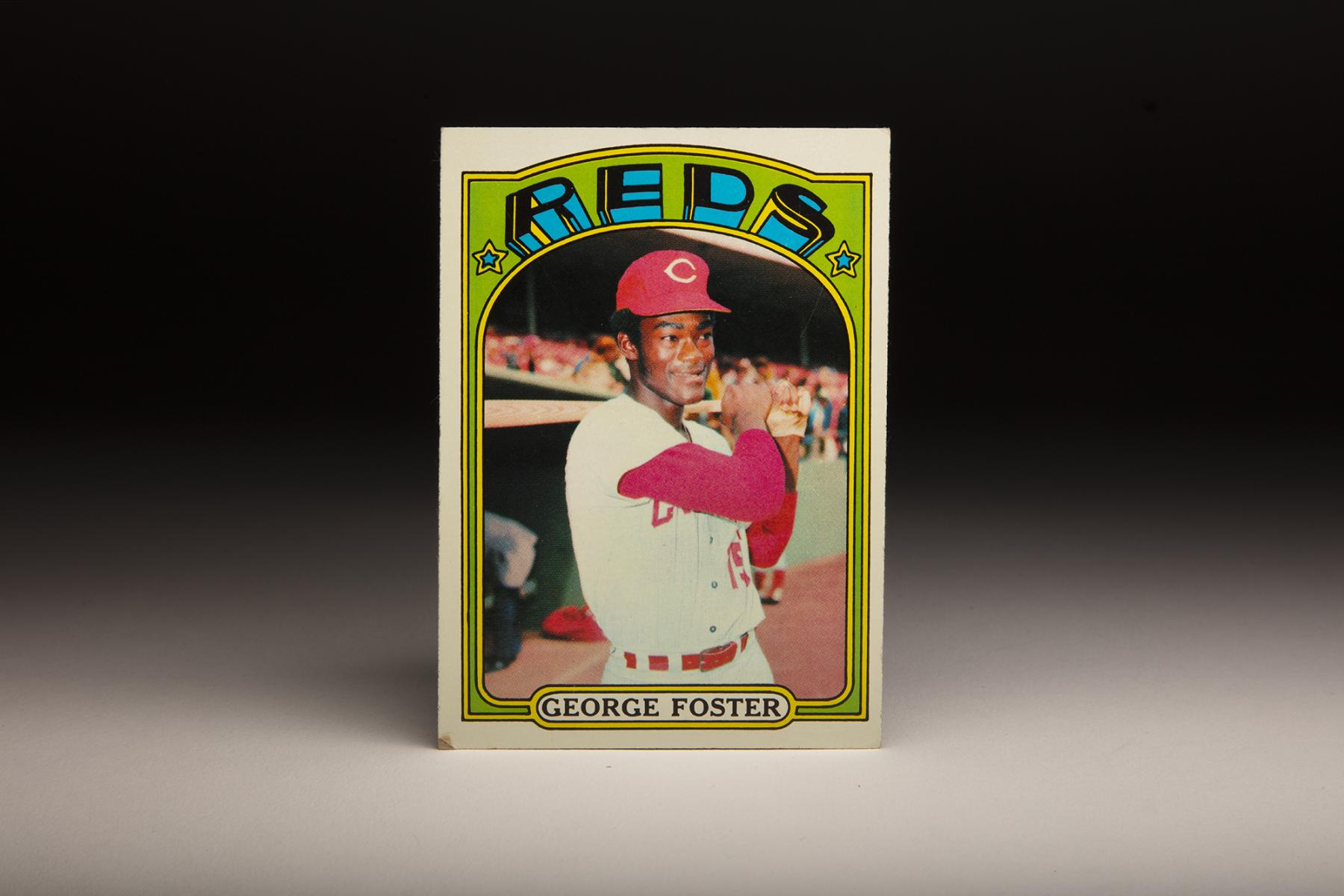

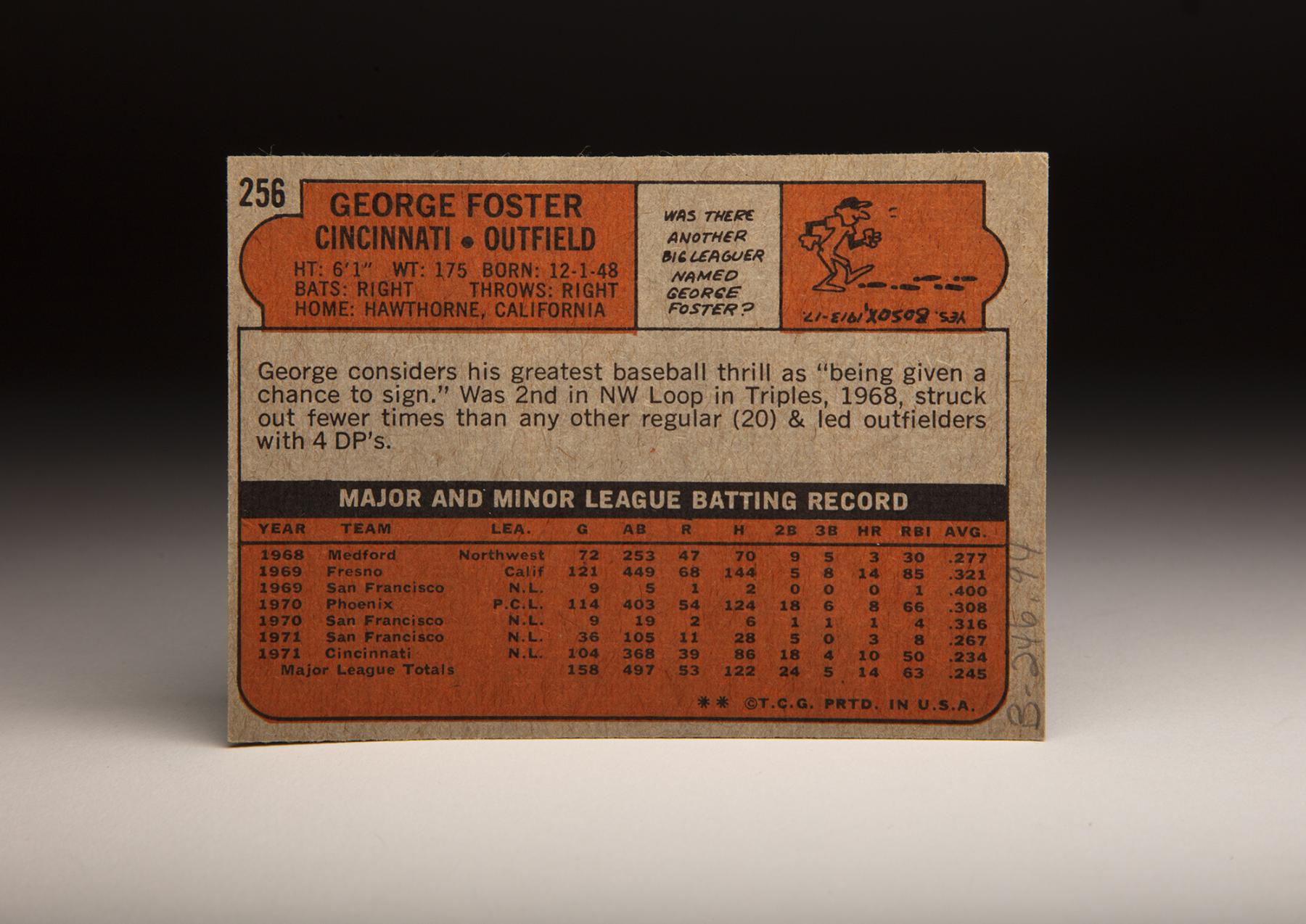

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps George Foster

From 1966 to 1989, 24 big league seasons came and went.

One – only one – featured a player with at least 50 home runs.

When George Foster hit 52 long balls in 1977, the baseball world stood in awe. It was unexpected, inspiring and – for Foster – career changing.

But back when he posed for the photo for his 1972 Topps card, all that must have seemed like a pipe dream for a player who took the long road to stardom.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Born Dec. 1, 1948 in University of Alabama football country in Tuscaloosa, Foster moved to the Los Angeles neighborhood of Hawthorne, Calif., as a youngster. After playing ball at a junior college, Foster was taken in the third round of the January 1968 MLB Draft by the Giants, and following a strong season at Class A Fresno in 1969, the Giants brought him to the big leagues that September at the age of 20.

He had another cup of coffee with the Giants in 1970, then made the big league roster as a reserve in 1971 – only to be traded to the Reds on May 29 in exchange for Frank Duffy and Vern Geishert. With Reds star center fielder Bobby Tolan out for the season, Foster stepped in and played 104 games with Cincinnati – hitting .241 in a combined 140 games but striking out 120 times, a total considered unsightly for that era.

Foster spent the 1972 season as a reserve after Tolan returned, appearing in just 59 games but earning a place in Reds history when he scored the series-clinching run on a wild pitch in the bottom of the ninth of Game 5 of the NLCS against the Pirates.

The Reds sent Foster to Triple-A Indianapolis for most of the 1973 season, but he returned to Cincinnati fulltime in 1974 as a bench player. Then in 1975, Foster won the Reds’ left field job when Pete Rose was moved to third base.

In 134 games, Foster hit .300 with 23 home runs and 78 RBI – helping the Reds win the World Series against the Red Sox. The next year, Foster was even better, hitting 29 home runs and driving in a big league-best 121 runs to finish second in the National League Most Valuable Player voting.

The Reds again won the World Series, and Foster – at age 27 – seemed to be the young star that would keep Cincinnati’s dynasty intact.

In fact, the Reds failed to advance to the postseason for just the second time in six seasons in 1977. But Foster captured the national spotlight by leading the NL in home runs (52), RBI (149), runs (124), slugging percentage (.631) and total bases (388) en route to the Most Valuable Player Award.

The following year – a down year for Foster – he led the league with 40 home runs and 120 RBI. For many, George Foster had evolved into the game’s most dangerous slugger.

In 1979, Foster appeared in only 121 games due to injuries but still hit 30 home runs and tallied 98 RBI as the Reds won another NL West title.

He finished third in the 1981 NL MVP voting in 1981 after hitting 22 home runs to go with 90 RBI in the strike-shortened campaign.

But with free agency approaching and coming off his age-32 season, Foster was traded to the Mets for Greg Harris, Jim Kern and Alex Trevino on Feb. 10, 1982.

He quickly agreed to a five-year, $10 million contract with New York, but never found the groove that he left behind in Cincinnati.

By 1986, the Mets were ready to return to the postseason, but Foster was not in their plans. He was released on Aug. 7, 1986, missing out on the team’s run to the World Series title.

After hooking on with the White Sox a week after he was cut, Foster appeared in just 15 games for Chicago before his career came to a close.

In 18 seasons, Foster hit .274 with 348 home runs, 1,239 RBI and 1,925 hits.

He was named to five All-Star Games, and – for a period of time – was unquestionably the game’s most feared hitter.

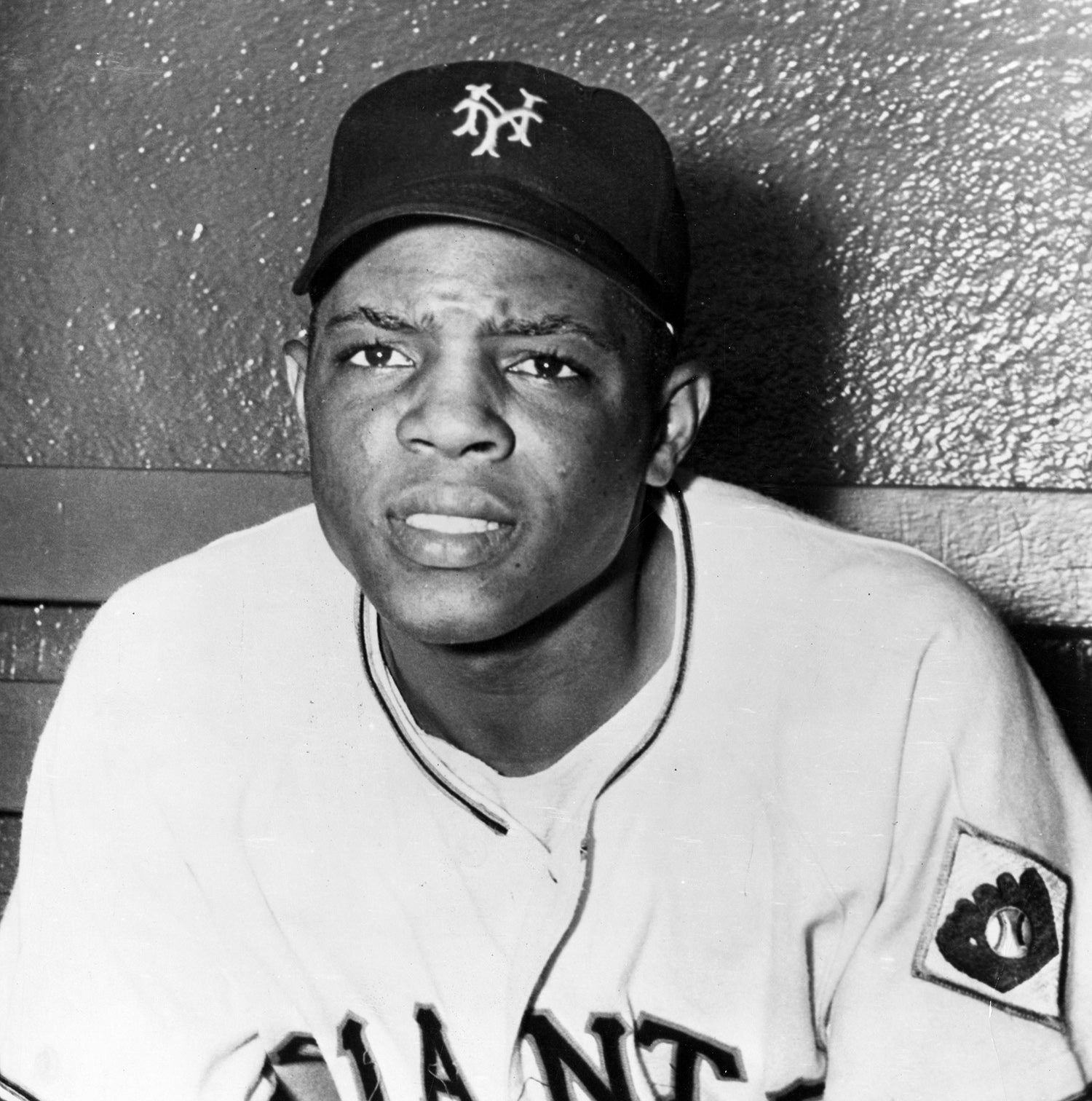

Willie Mays hit 52 home runs in 1965. Cecil Fielder hit 51 bombs in 1990. In between, however, George Foster defined home run excellence for nearly a quarter of a century.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

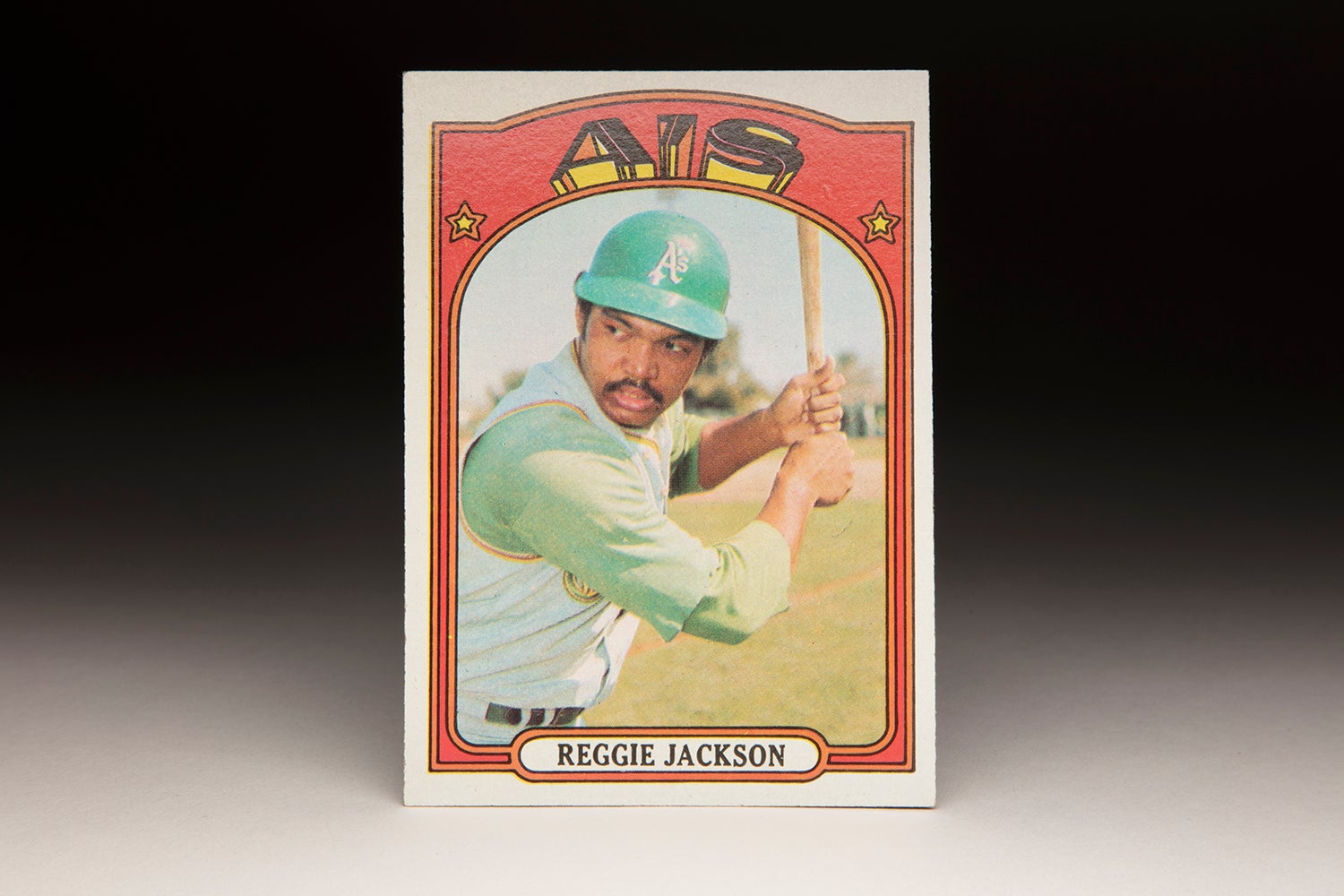

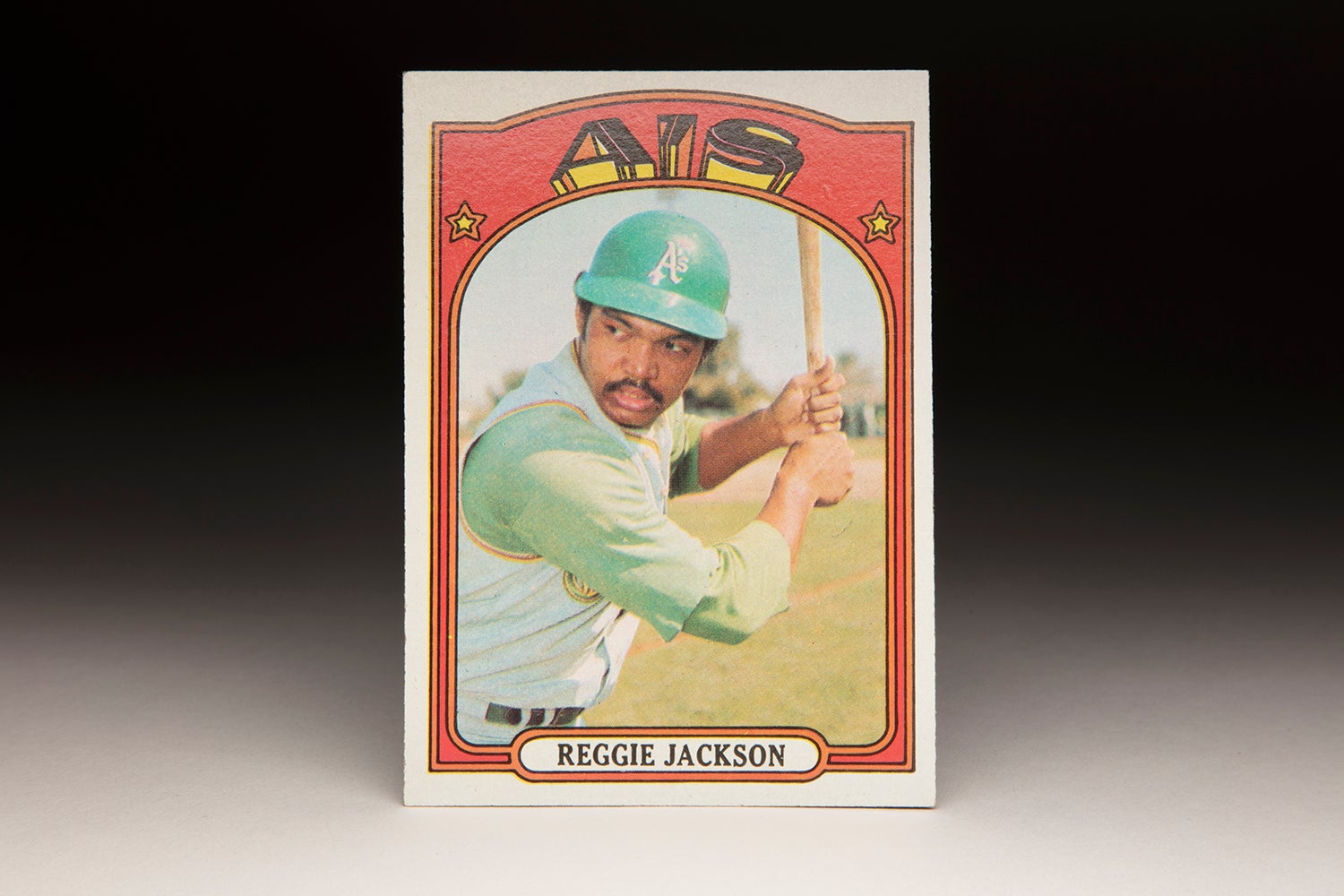

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Reggie Jackson

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Mudcat Grant

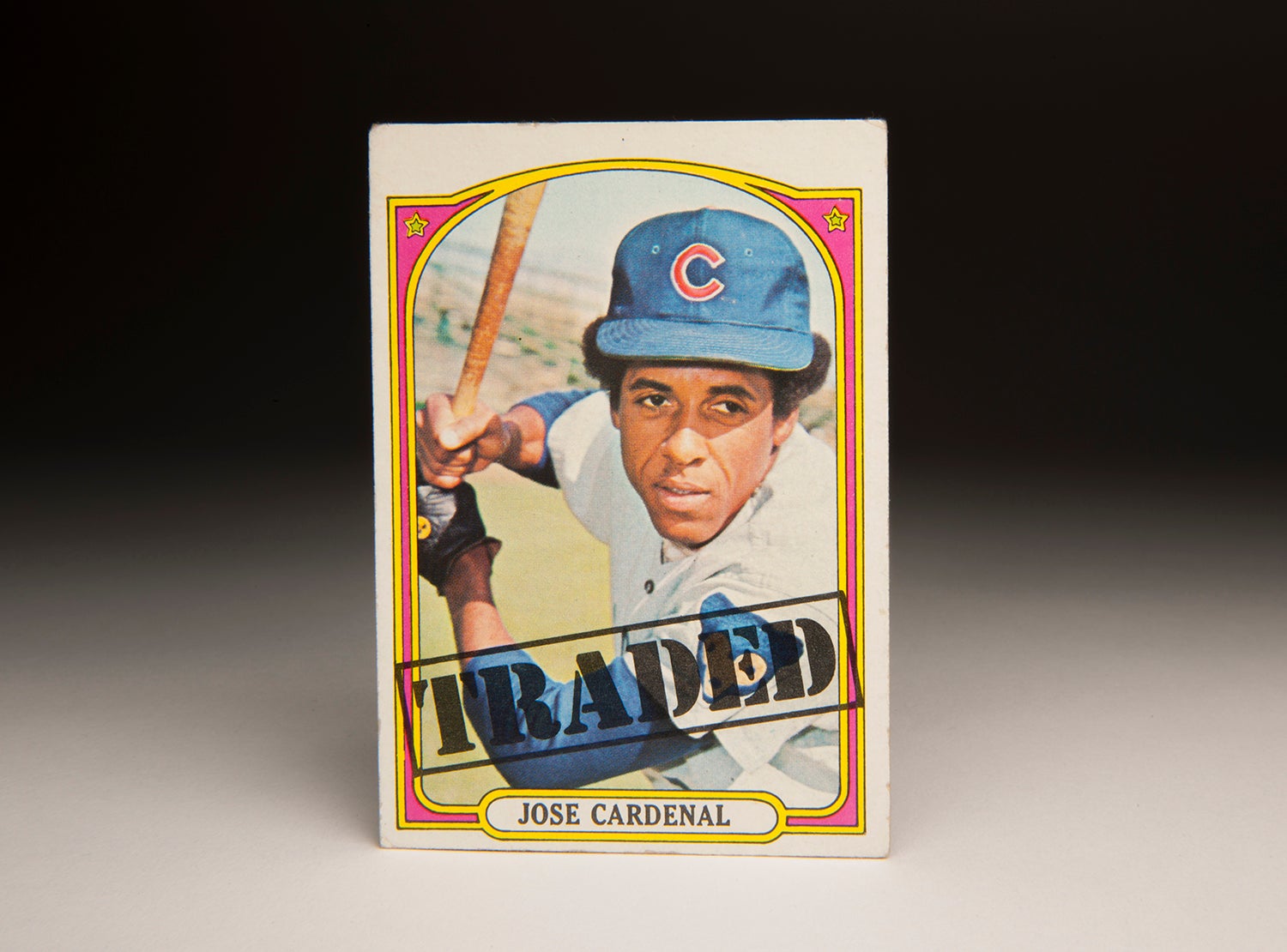

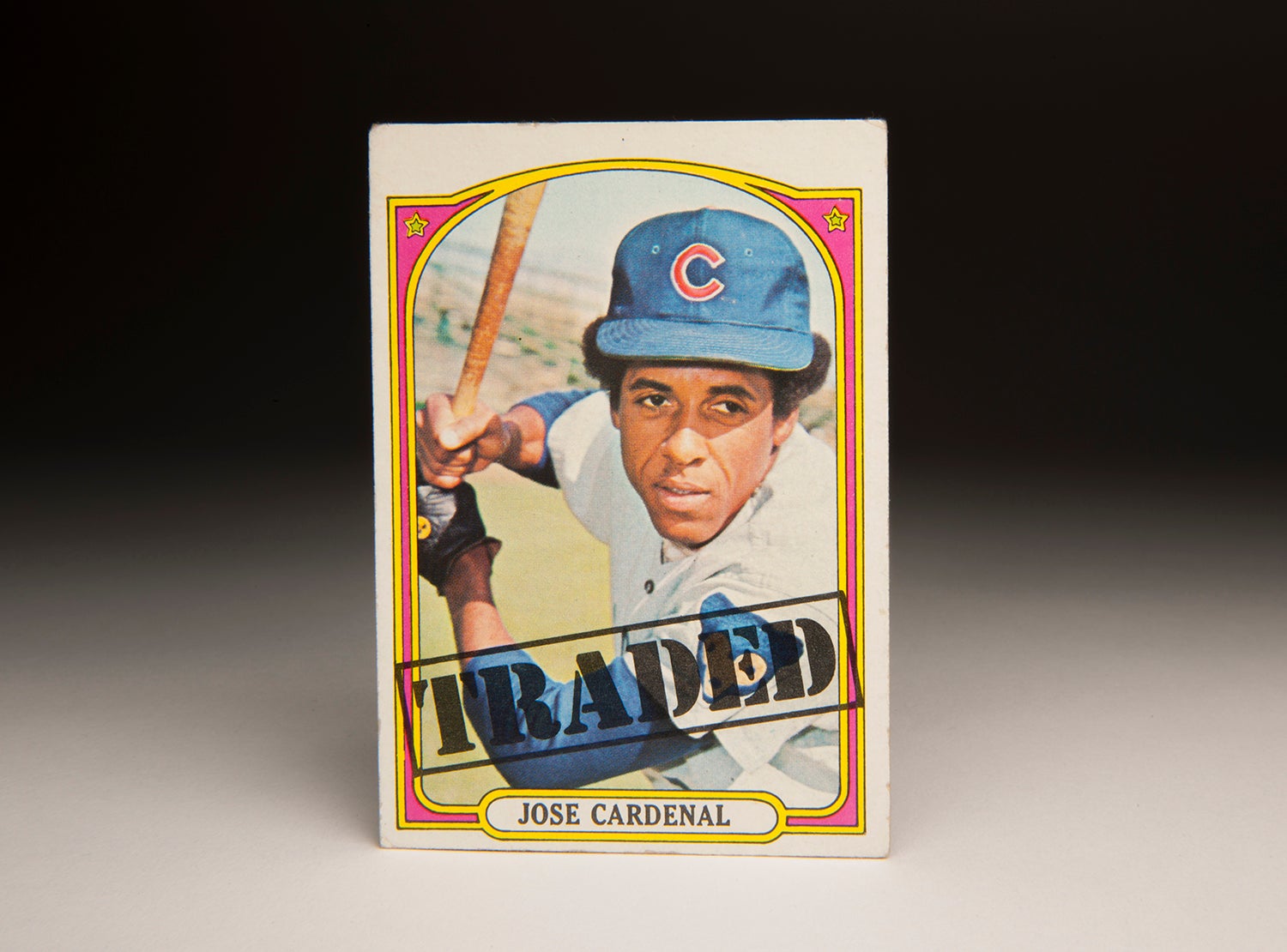

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps José Cardenal

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Blue Moon Odom

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Reggie Jackson

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Mudcat Grant

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps José Cardenal