- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 & 1975 Topps Jimmy Wynn

#CardCorner: 1968 & 1975 Topps Jimmy Wynn

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Every World Series, I tend to play a little bit of a mental game. I think of the two teams playing in the Fall Classic – in this case, the Houston Astros and the Los Angeles Dodgers – and then I try to come up with a significant player who had ties to both teams. That lucky player then becomes the subject of one of these Card Corner features.

Inevitably, there are some names who come to mind. For example, there is Hall of Famer Don Sutton, who had dominant seasons with both the Dodgers and Astros and helped push each franchise to the postseason. I also remember Jerry Reuss, a very good left-handed pitcher with both clubs. Then there is Davey Lopes, the great basestealer who begin his career with the Dodgers and ended it with the Astros. Among current-day players, there is Josh Reddick, now playing for the Astros after spending the tail-end of 2016 in Los Angeles.

These are all good examples, but the player who seems to be the best fit for this exercise is the perpetually underrated Jimmy Wynn. For some reason, when I think of the Astros and the Dodgers in tandem, Wynn is the first player who crosses my mind. He is also a player who somewhat epitomizes the fortunes of the two franchises.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Wynn spent the early part of his career with the Colt .45s/Astros, coinciding with a stretch of years in which the recent expansion franchise never made the postseason. Wynn then joined the Dodgers, and voila! – the team advanced immediately to the World Series, continuing a run of excellence for a franchise that had already won so much during the 1950s and ’60s.

Interestingly, Wynn did not start his professional career in the system of either the Astros or the Dodgers. In 1962, the Cincinnati native signed his first pro contract with the hometown Reds, who assigned him to Tampa of the Class D Florida State League. A combination third baseman/outfielder in his early pro career, Wynn played exceedingly well for Tampa, hitting 14 home runs, stealing 20 bases, and drawing 113 walks – a remarkable show of patience for a young hitter who was all of 20 years old.

Wynn’s performance became even more impressive in light of the racism he faced while playing in the South. The perils of Jim Crow segregation, along with catcalls from the stands, made it difficult for black players like Wynn and Lee May. Thankfully, Wynn’s managers (Johnny Vander Meer and Hersh Freeman) treated the team’s black players fairly, softening the blow of some of the cultural bigotry.

The Reds considered Wynn a premier prospect, but he would never make it to Cincinnati. After that spectacular debut in the Florida State League, Wynn was made available in the old first-year player draft, which allowed lesser teams to select players who had been left off their teams’ 40-man roster. Wynn was one of those players. As an expansion team, the Houston Colt .45s (as the Astros were called during their first three seasons) selected Wynn in the first-year player draft, paying the Reds a small sum of cash in return. It would turn out to be one of the best transactions the Houston franchise would ever make.

Wynn started the 1963 season at Double-A San Antonio, but he would not remain there for long. Fully committed to youth, the Colt .45s promoted Wynn to Houston in July, using him as a utility man who could play shortstop, third base, and the outfield. In 70 games, he hit .244 with four home runs, numbers that were actually respectable given how quickly the Colt .45s had rushed the 21-year-old to the big leagues.

The 1963 season also allowed Wynn to take part in an intriguing piece of baseball history. On Sept. 27, Colts manager Harry Craft fielded the first all-rookie lineup in 20th century history. Houston’s starting nine featured all freshmen, including Wynn in center field, future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan at second base and soon-to-be star Rusty Staub at first base.

In 1964, the Colt .45s abandoned the idea of using Wynn as an infielder and made him their Opening Day center fielder. He would soon lose the job – and his place on the big league roster. An early season slump resulted in his demotion to Triple-A Oklahoma City, where he hit well enough to earn another promotion in September. Between the two stints with the Colt .45s, Wynn batted only .224. Still only 22 years old, Wynn needed a little more time to blossom at the major league level.

After the fits and starts to the first two seasons, Wynn developed into a star in 1965. The breakout coincided with the franchise’s moving into the major leagues’ first indoor ballpark, the Astrodome, and being renamed the Astros. Becoming Houston’s everyday center fielder and the No. 3 hitter in the batting order, Wynn erupted with 22 home runs, 43 stolen bases and an OPS of .841. He hit far better on the road than at home; he hit only .247 with just seven home runs in the Dome, where the lengthy dimensions and difficult sight lines made it harder to hit. With a better hitting environment at home, Wynn’s overall numbers might have been even more impressive.

After a solid but unspectacular 1966, the Astros expected a breakthrough into stardom in 1967. “He is the Willie Mays type,” Astros manager Grady Hatton told sportswriter Pat Harmon during the spring of ’67. “Exciting. He can hit, run, field, hit with power, steal bases – the kind of ballplayer you pay money to watch.”

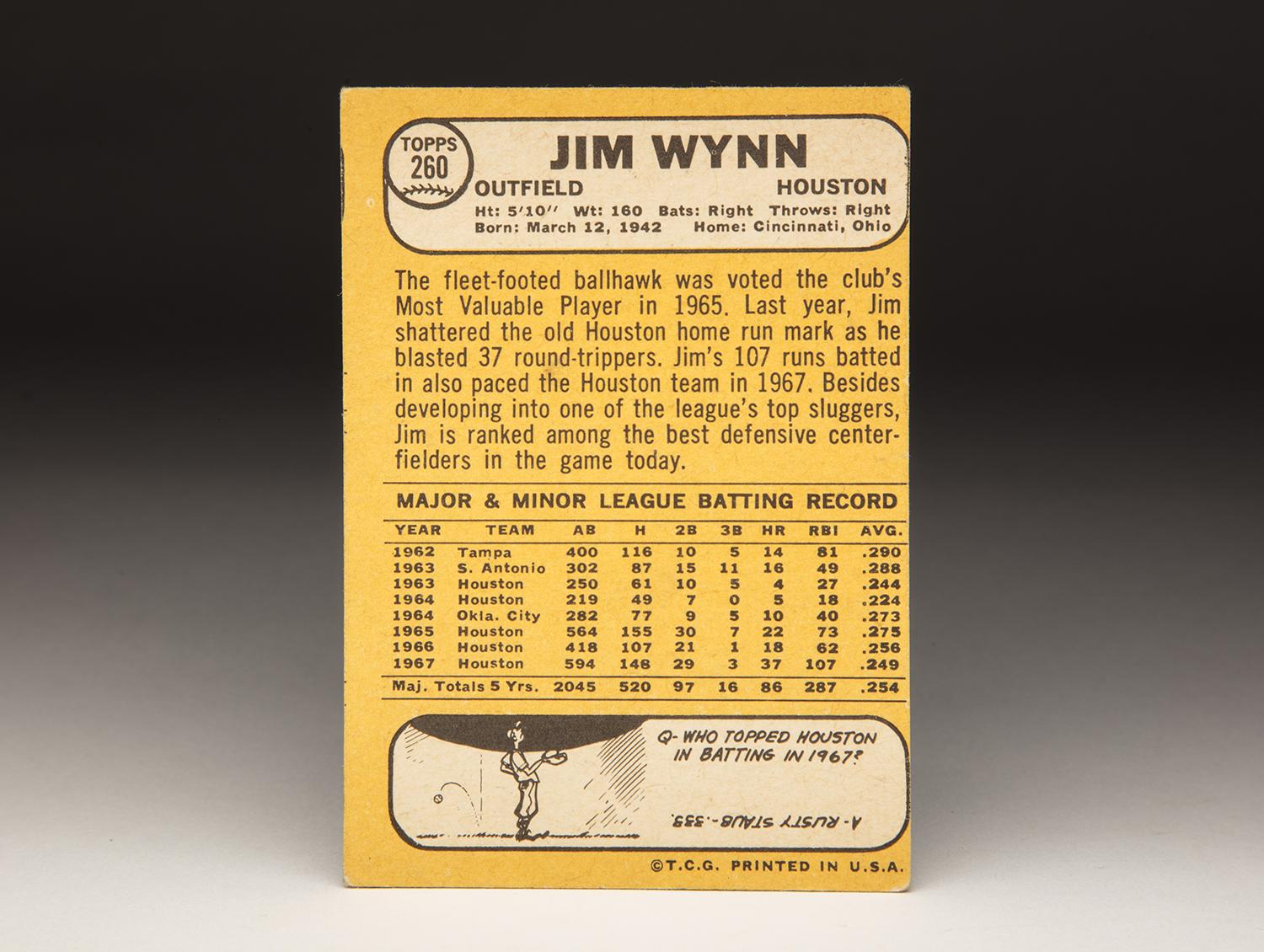

Wynn did not sink under the weight of such expectation. Instead, he exploded with a 37-home run season, a dramatic level of production in the pitcher’s era of the 1960s. (Only Hank Aaron hit more home runs in the National League that season.) On June 11, Wynn hit arguably the most impressive home run of his career. Playing against the Reds, Wynn powered a towering drive that cleared the enormous Crosley Field scoreboard, flying over the “Webber’s Sausage” sign and landing onto a nearby freeway. Though no official measurement was calculated, some observers claimed the ball traveled over 500 feet. Just four days later, Wynn put up one of the most remarkable hitting displays of the decade. Playing against the San Francisco Giants at the Astrodome, Wynn hit three home runs. Each one of the long balls traveled more than 400 feet.

For the first time in his career, Wynn made the All-Star team. His season also represented payback against the skeptics who claimed that he was too small to play in the major leagues or hit with any power. At all of five feet, nine inches, and 165 pounds, Wynn did not look the part of a power hitter. But his bat speed and his physical strength dictated otherwise.

Wynn’s lack of size, contrasted against his remarkable power, led to a nickname courtesy of Houston sportswriter John Wilson. Writing for the Houston Chronicle, Wilson dubbed Wynn “The Toy Cannon.” The name caught on with the rest of the Houston media – and Astros fans.

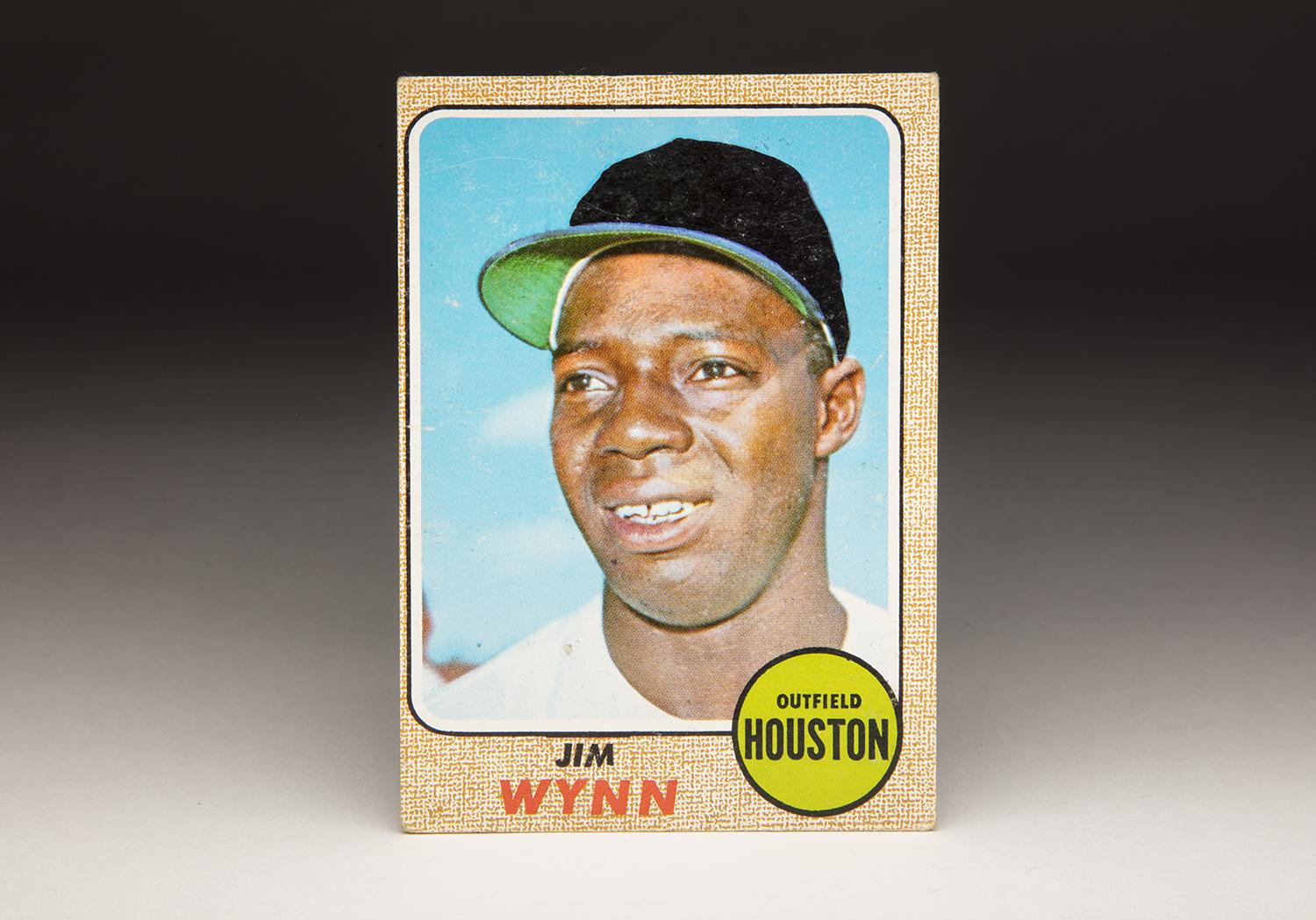

Fresh off his dynamic season, Topps produced an unusual card of Wynn during the spring of 1968. The card showed him from the neck up, wearing a strange cap with a blue bill but a blackened crown, the latter obliterating the Astros’ colors and log from the cap. Wynn had not been traded during the winter; he remained with the same team for which he had debuted in 1963. So why did Topps airbrush black over the cap?

An examination of all the Astros player cards in the 1968 set reveal that the name of “Astros” is nowhere to be found. In some cases, Topps showed Houston players without caps or with upturned caps; in other cases, like the Wynn card, the logo was obliterated. The reason behind this has never been confirmed by an official source, but the unofficial legend involves a 1968 conflict between the Astros and the Monsanto Company, the makers of “Astro Turf.” The two organizations disputed who had the legal rights to the name. Apparently not wanting to get involved in the conflict, Topps chose to stay out of it completely and take the safe route by eliminating references to “Astros” on all of its cards. Even the greenish circle in the lower right-hand corner of the Wynn card says “Houston,” and makes no mention of the team nickname of “Astros.”

The dispute, while intriguing, mattered little to Wynn. Of more concern was the Astros’ decision to move Wynn out of center field and make him a left fielder. Not only did Astros management believe that Wynn was a subpar center fielder, but Grady Hatton had benched him at least twice for what he considered indifferent play. Even after Hatton was fired in June of ’68, his replacement, Harry “The Hat” Walker, also sat down Wynn for a failure to hustle.

In addition, Walker believed that Wynn needed to change his hitting approach. Wanting Wynn to cut down on his strikeouts, Walker repeatedly hounded Wynn about shifting his game from power to contact. “He kept telling me I’d hit .300 if I just choked up on the bat, went to the opposite field, and concentrated on average,” Wynn revealed in a 1974 interview with Ron Fimrite of Sports Illustrated. “No way [was I going to do that]… I didn’t get all those home runs being a punch-and-judy hitter. I guess when you’re short, managers have a tendency to mess with you more.”

The disagreement over hitting philosophy led to tensions between Wynn and Walker. Wynn also believed Walker to have racist attitudes.

In spite of the problems with his manager, Wynn continued to annihilate National League pitching. From 1968 to 1970, Wynn remained a powerful and consistent run producer, reaching a high point in 1969. That summer, he hit 33 home runs, drew 148 walks and finished 15th in the National League MVP voting. His numbers, coming against the horrendous hitting conditions of the Astrodome, stood out as astonishing.

Wynn experienced a temporary downturn in 1971, when a domestic dispute with his wife resulted in him receiving a stab wound, and ultimately a round of abdominal surgery. Bothered by the after effects of the incident, both physically and mentally, Wynn saw his batting average dip to a career-low .203. The season reached its lowest point in July, when Wynn ignored the take sign from his third base coach on a 3-0 pitch. After the game, Walker summoned Wynn to his office, where the two men engaged in a loud shouting match.

The disagreement led to speculation that once winter came, either Wynn would be traded, or Walker would be fired. Neither of those developments occurred. Wynn bounced back with a much better season in 1972, when he walked 103 times, reached base 39 percent of the time, and hit 24 home runs. The season did not go as well for Walker, who was fired in August.

Leo Durocher replaced Walker and made a change to the Astros’ lineup. Wanting to take advantage of Wynn’s ability to draw walks, Durocher moved him into the leadoff spot. Wynn did not care for the move; he considered himself a run producer, not a tablesetter.

Perhaps bothered by the leadoff role, Wynn slumped in 1973, marking his second poor season in the last three. At one point, he endured a 0-for-28 stretch, resulting in Durocher moving him down to the seventh spot in the order. Concerned that age was beginning to catch up to the 31-year-old, the Astros decided to trade their veteran slugger. At the 1973 winter meetings, the Astros dealt Wynn to the rival Dodgers for veteran left-hander Claude Osteen.

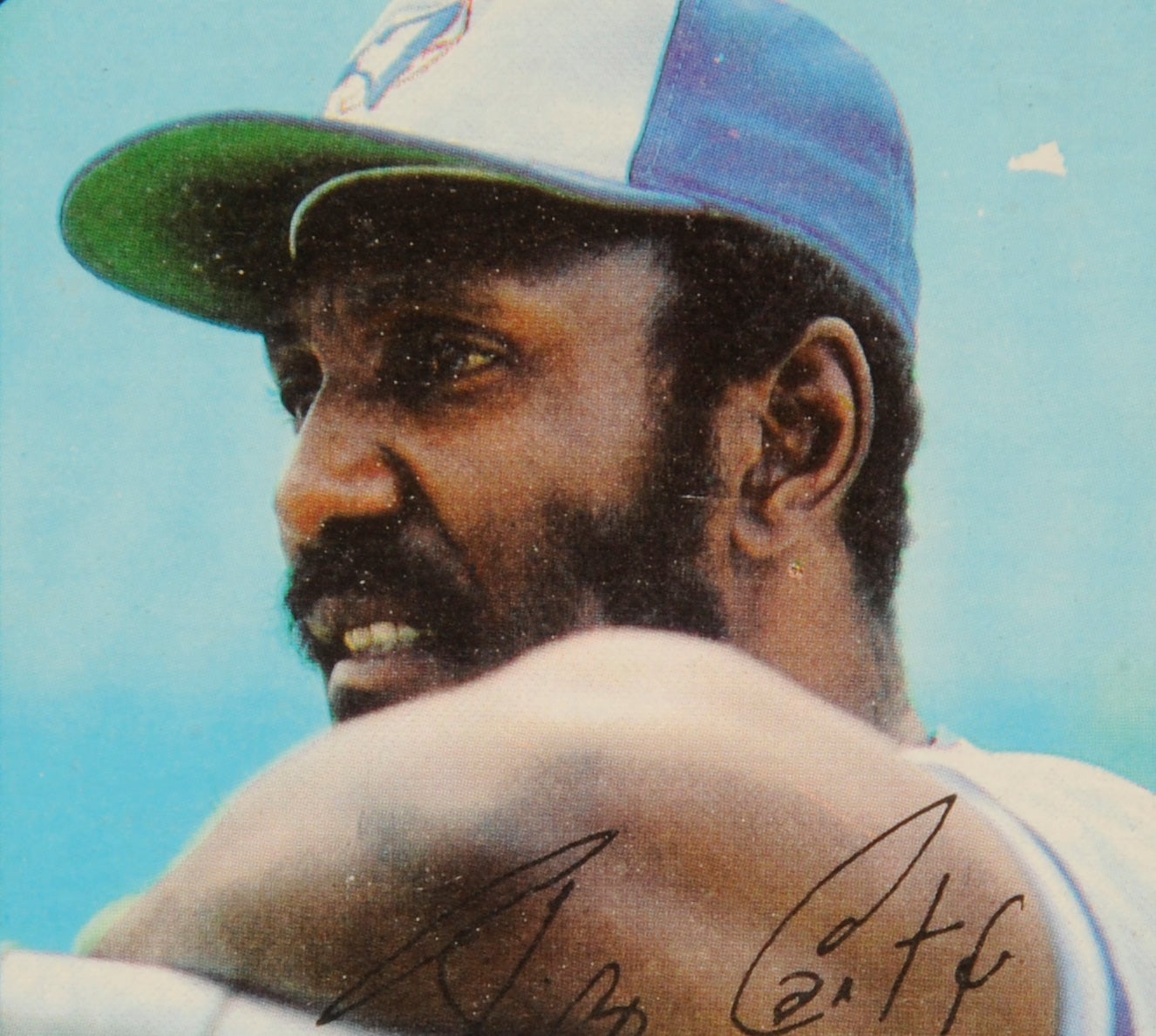

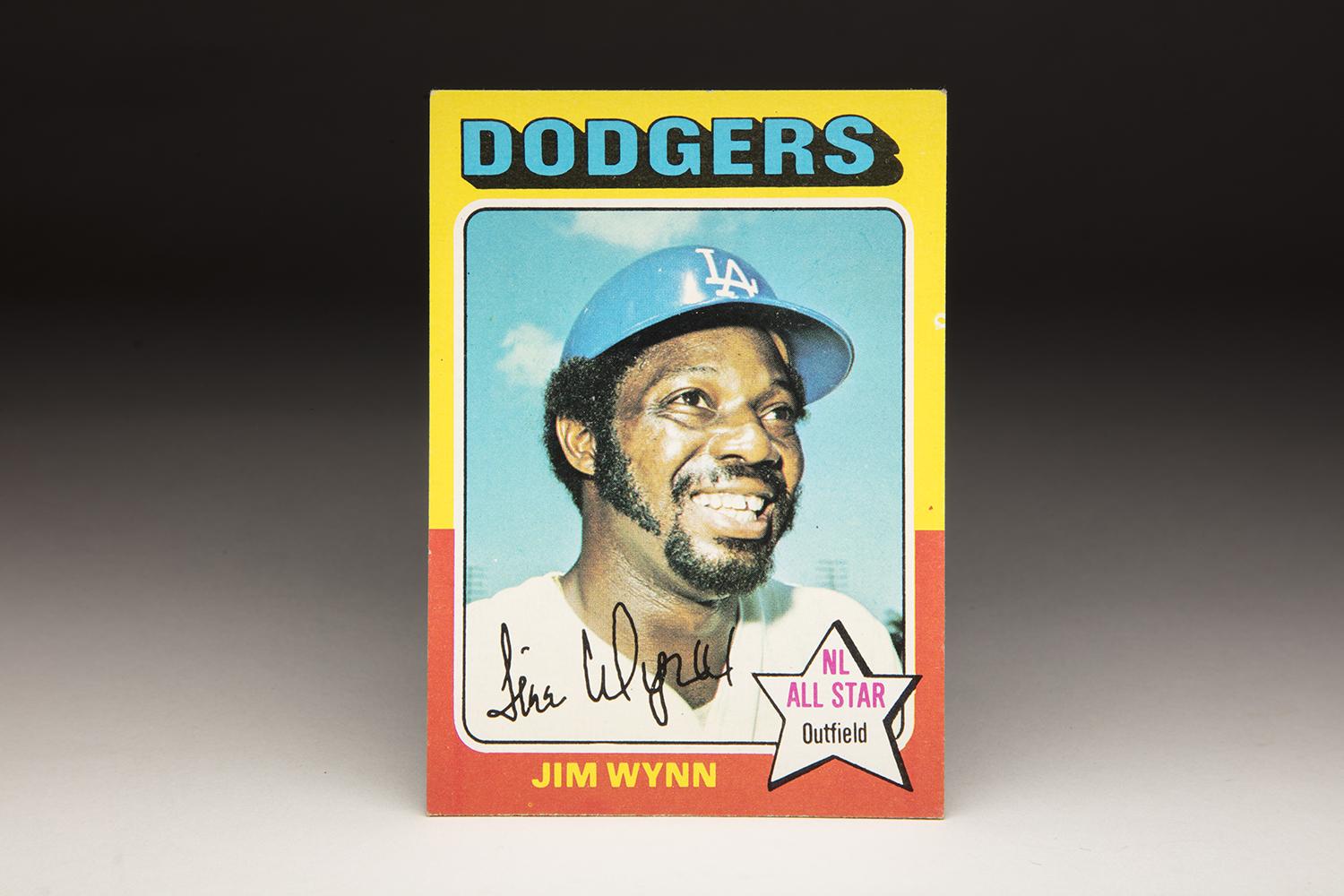

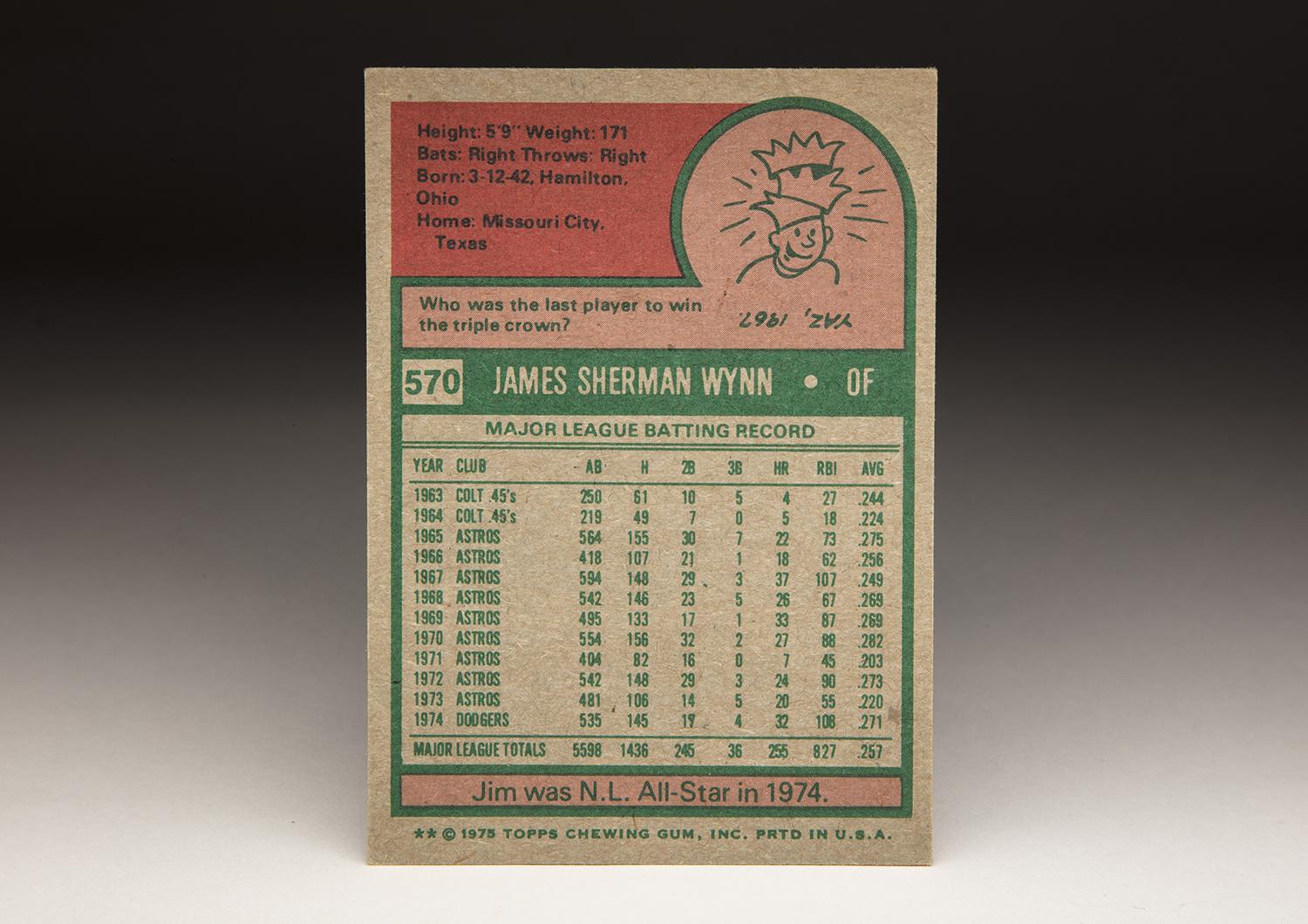

The trade came too late for Topps to have an updated card of Wynn as a Dodger in 1974, but the company did issue a “Traded” card for him later in the summer. (For some reason, Topps always listed him as “Jim Wynn” and not “Jimmy Wynn” on his cards. I’m not sure why.) The card featured banners with “Los Angeles” and “Dodgers” on the top and bottom, but the photograph was still an old one, with Wynn’s cap turned upward to hide the Astros’ logo from sight. It was not until 1975 that Topps showed Wynn wearing an actual Dodgers uniform. By now, Wynn’s appearance reflected the changes in fashion and grooming that baseball underwent in the early 1970s. On this card, complete with multi-colored borders, Wynn sports a mustache, beard, and longer hair, in contrast to his clean-shaven look during the Houston years.

Despite struggling with a severe shoulder injury, Wynn found a home in LA playing for Walter Alston. The Hall of Fame skipper batted Wynn third, played him in center field, and encouraged him to go for the long ball. Wynn proceeded to hit 32 home runs and draw 108 walks in 1974, leading LA to the pennant and a World Series berth against Oakland. Fans situated in the left field bleachers at Dodger Stadium responded to Wynn by turning the area into “Cannon Country,” which they marked with a large banner.

Wynn played so well that he finished fifth in the National League MVP vote. Some historians and Sabermetric analysts believe that he should have won the award over teammate Steve Garvey. Instead, Wynn settled for Comeback Player of the Year honors.

Wynn remained productive in 1975, and made his second straight All-Star Game, but did not play at the same level as he had in ‘74. That prompted another trade, this time to the Atlanta Braves for a younger outfielder, Dusty Baker. Wynn hit 17 home runs, but batted only .204, convincing the Braves that his days as an everyday player were over. But his lone season in Atlanta did not come without some fanfare. At the urging of new owner Ted Turner, a number of Braves players sported nicknames on the backs of their jerseys. Wynn went along with the Turner directive, putting the word “Cannon” on his jersey – shorthand for The Toy Cannon.

Although manager Dave Bristol praised Wynn for his hustle and leadership, the Braves decided that it was time to clear out his contract to make room for newly signed free agent outfielder Gary Matthews. The Braves sold Wynn to the New York Yankees, receiving a cool $100,000 in return. On Opening Day, Wynn hit a memorable home run at Yankee Stadium, but otherwise struggled for the Yankees, leading to his release in midsummer. He then put in some time with the Milwaukee Brewers, appearing in 36 games, but he no longer exhibited his trademark bat speed. After the season, the Brewers released him. Two years later, Wynn attempted a comeback in the Mexican League, but his skills were gone, forcing him to retire for good.

Wynn’s departure from baseball took place without fanfare. To this day, he remains underrated by much of the media, perhaps because he never hit for high averages and only once received the exposure that comes with World Series play. But with his power, ability to draw walks, and his speed, Wynn quietly put up a fine career that established himself as one of the most dangerous hitters in the game from the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s.

His playing days over, Wynn struggled to find his niche. He took a job with a beverage company, but the position was largely superficial and involved him making only the occasional public appearance. He also became separated from his two children, who remained with his ex-wife.

In the late 1980s, Wynn began to undergo a turnaround to his life. He took a job with the Astros in community relations, giving him the chance to speak to youngsters about the importance of staying in school and avoiding the temptations of drugs and alcohol. Wynn has excelled in the role, and along with former Astros All-Star Jose Cruz, continues to serve the team as a community outreach executive. He has also remarried and experienced a reconciliation with his children.

Wynn remains a revered figure in Houston, where the Astros have not only retired his No. 24 but also opened the Jimmy Wynn Training Center, a baseball academy for city youth. It’s a fitting tribute for one of the first stars in the history of the Astros. The man known as The Toy Cannon, who has encountered so many struggles along the way, has found resolution and redemption in the town where he became a baseball star.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

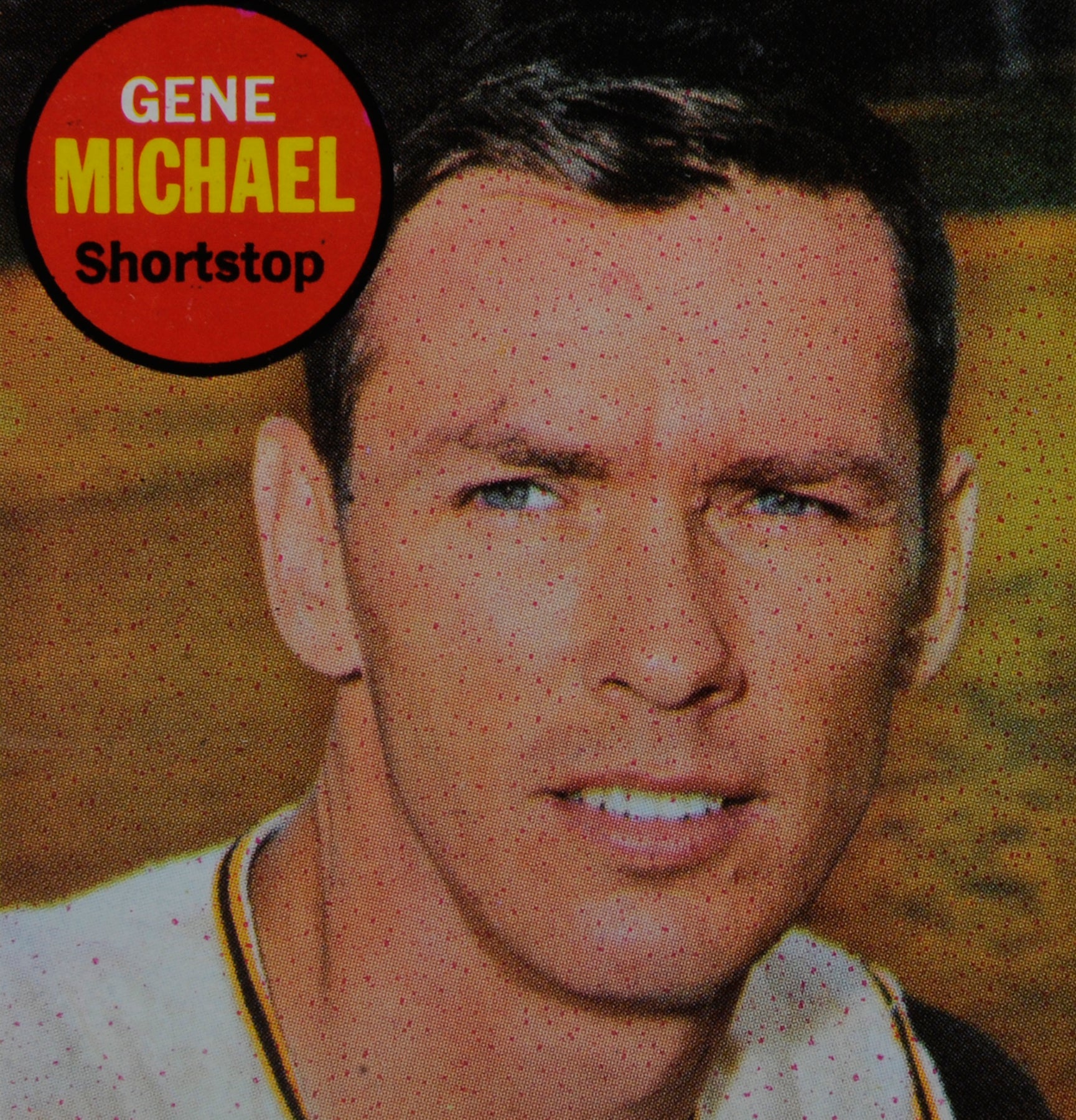

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

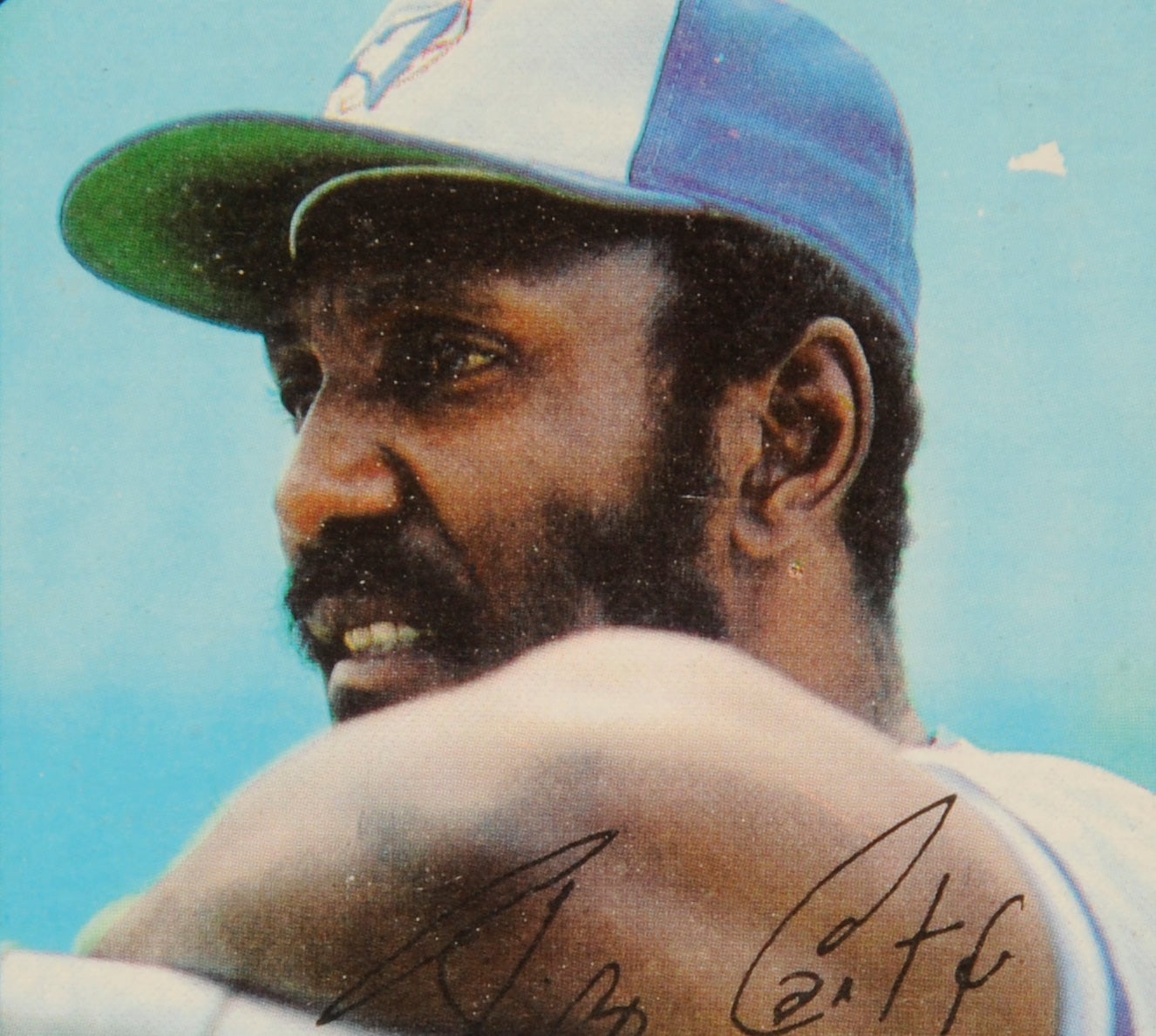

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan