- Home

- Our Stories

- Bud Selig brought baseball back to Milwaukee

Bud Selig brought baseball back to Milwaukee

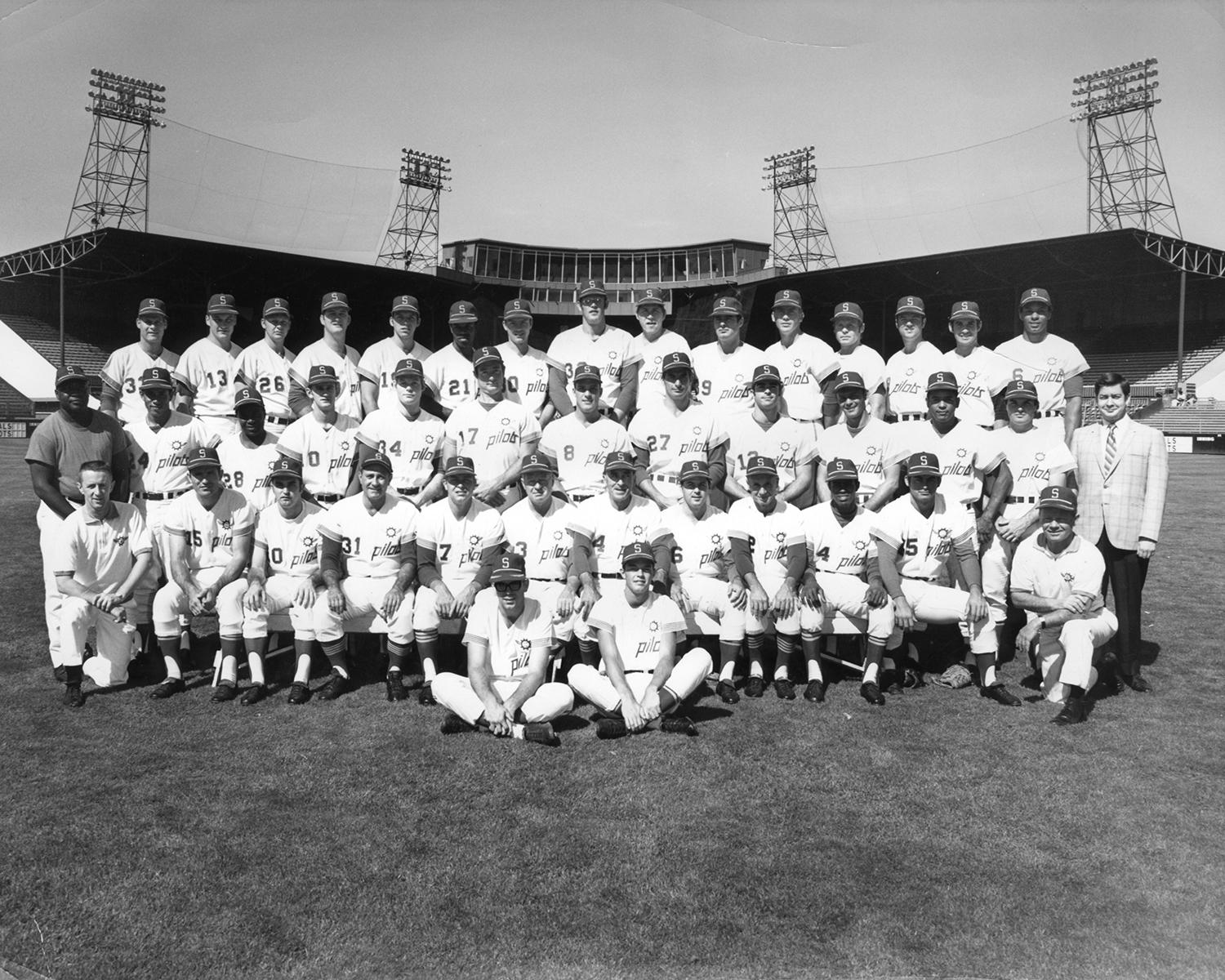

The smiles on the faces of William Daley and the Soriano brothers, Dewey and Max, as seen in the Seattle Pilots’ 1970 Log Book, could barely overshadow the turmoil afflicting the men and their franchise.

Struggling to a last place finish in the American League West in 1969, with a 64-98 record under manager Joe Schultz, the Pilots managed to avoid completing the season in the American League basement attendance-wise. The 677,944 who came to old Sick’s Stadium that year totaled more than four other major league teams, including fellow 1969 expansionist San Diego. But that might have been one of few bright spots that year.

The 1970 season would promise change for baseball in Seattle. And in the early hours of the morning on April 1, 1970, the Seattle Pilots – with the help of 2017 Hall of Fame electee Bud Selig – became the Milwaukee Brewers.

Early in November 1969, Pilots general manager Marvin Milkes dismissed the coaching staff. A few weeks later, it was Pilots pilot Schultz’s turn.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Milkes made a statement to the players by hiring a no-nonsense manager in Dave Bristol, but at the same time made a statement to doubters.

“I want to assure the baseball world and Pacific Northwest fans that this will be a stable organization and we can expect to see Major League Baseball here for many years to come,” Milkes told reporters at Bristol’s introductory press conference.

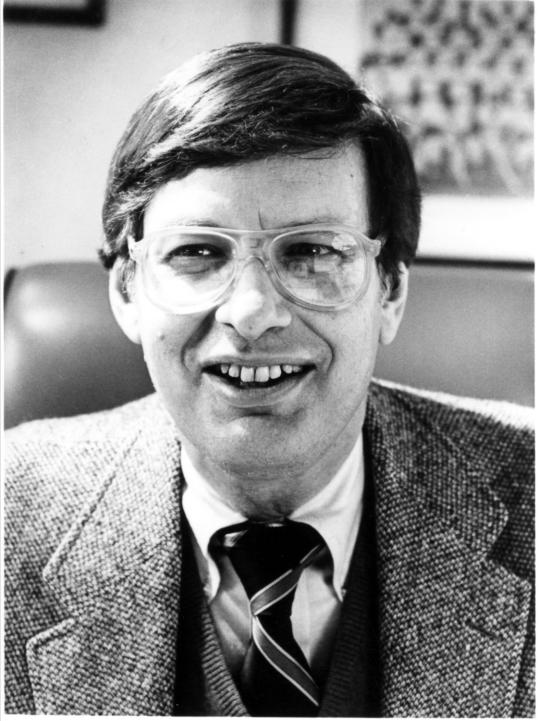

At the same time, an auto industry businessman in the Milwaukee area was sensing an opportunity. Allen H. “Bud” Selig, a child of Eastern European immigrants, was busy carving out a name for himself in baseball circles. He attended minor league Milwaukee Brewers games at Borchert Field while a youngster, his mother encouraging his interest in the sport. When the National League’s Braves abandoned Boston for a new stadium in Milwaukee, Selig went to work.

“(When the Braves) went public in 1963, I was the largest public shareholder,” Selig recounted in a 2011 interview with the University of Wisconsin alumni magazine. “But I didn’t control the fate of the Braves. I certainly would have (kept them in Milwaukee) if I could.”

The Braves left for Atlanta following the 1965 season, and County Stadium would lose 81 home games per year. Selig did not wait for the team to split town to take action. He and other investors created an organization called Milwaukee Brewers Baseball Club, Inc., which, that August, applied to National League president Warren Giles for an expansion franchise beginning in 1966. The application was rejected that winter, largely due to Wisconsin’s anti-trust lawsuit against the Braves and the National League, as well as the political atmosphere in Milwaukee.

Undaunted, Selig sought other avenues, those in the American League. In 1967, Selig and his investment group scheduled an exhibition game at County Stadium on July 24 between the White Sox and the Twins.

“This exhibition game is an important part of our continuing program to reestablish Milwaukee as a major league city,” Selig told reporters at the time.

Meanwhile, Selig was overshadowed during the 1967 season by rumors intimating that Athletics owner Charles Finley wanted to move his franchise to Milwaukee from Kansas City. Finley denied the rumors. Following the season, Selig and his group reiterated its interest in a National League expansion franchise for Milwaukee in 1969. The American League had already chosen Kansas City and Seattle. The National League would choose its new clubs later.

However, the White Sox-Twins exhibition game on July 24, 1967, had proven fruitful, with 51,144 attending – at that point the largest-ever crowd for a baseball game in County Stadium’s history. Selig contracted with Arthur and John Allyn, the White Sox owners, for the team to play nine regular season games and one preseason exhibition game in Milwaukee in 1968. The White Sox claimed to be “tickled” at the set up.

“This step will add impetus to the return of a full schedule to Milwaukee,” said Rudy Schaeffer, business manager for the White Sox. “Milwaukee rightfully belongs in the majors. We want to expedite it.”

Selig had support in the American League, but the National League still would not budge, denying the group an expansion franchise in May 1968.

Meanwhile, the Chicago White Sox games had been successful. More than 240,000 paying customers had attended the games at County Stadium, and Selig was feted by fans before the August 26 game against Detroit. Former Braves star Eddie Mathews, playing with the eventual world champion Tigers in his final season, also was honored. The Allyns scheduled 11 regular season games in Milwaukee for 1969.

Perhaps giving a dig to baseball’s senior circuit, Selig noted in January 1969 that “the American League came to us as friends when we needed friends.”

Meanwhile, one of the American League’s new entries, the Seattle Pilots remained within striking distance of .500 in the early going in 1969. By the time Seattle visited Milwaukee to play Chicago on June 16, 1969, both clubs were neck-to-neck in the standings, the Pilots at 26-32 and the Sox at 24-32. Chicago jumped out to an 8-1 lead and Billy Wynne went the distance for his first career win, as the White Sox coasted to an 8-3 victory.

Who knew that Milwaukee fans would be watching the ballclub which would play at County Stadium the following season?

The situation was not so rosy for the Pilots later in 1969. Frequent player moves and attendance regularly falling well short of Sick’s Stadium’s 19,800 capacity did not help the club’s ledgers. Losses on the field mounted as quickly as losses off the field. The team went 15-42 between July and August.

On Aug. 25, with the team on a 10-game skid, the tenure of Schultz was already questioned.

“Some say a manager who is loved by players and fans alike should be retained,” Pilots GM Milkes told reporters. “Well, I’m not conducting a love-in – I’m running a major-league baseball team.”

Schultz’s players snapped the losing streak the following day, edging the Orioles, but promptly lost their next six games.

Rumors circulating in late August were that the Pilots might fly to the Dallas-Fort Worth area for the 1970 season, but Texas millionaire and Kansas City Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt, who had been seeking a major league team of his own, denied those reports.

On Friday, Sept. 5, 1969, the mayor of Seattle brought the hammer down on the Pilots, threatening to evict the team from Sick’s Stadium if it did not pay $600,000 in rent by Monday, Sept. 8. Mayor Floyd Miller, following a meeting with an American League lawyer, relented on Sunday, allowing the team two more weeks to come up with the rent and a $150,000 surety bond. Meanwhile, Pilots brass maintained that the city failed to live up to his end of the deal by not bringing Sick’s Stadium up to American League standards.

By late September, Hunt presented Daley, Pilots chairman of the board, with an offer to purchase the club. Yet Daley rejected the offer, maintaining that the franchise would remain in Seattle. After the season’s end, though, it was known that the Pilots were for sale and listening to all potential suitors. Seattle president Dewey Soriano acknowledged the team lost over $300,000 in its first season, and Daley gave the city and its fans another campaign to prove themselves.

But a new possibility was arising – a move to Milwaukee.

On Oct. 20, 1969, Chicago Daily News editor John P. Carmichael said the Pilots would move to Milwaukee for the 1970 season, play as the Milwaukee Brewers, and be owned by a Milwaukee-based group. He claimed that “Milwaukee has virtually sewed up the franchise.” The next day, Leonard Koppett of The New York Times said that owners meeting in Chicago would consider the “final steps” of moving the club to Milwaukee.

Daley told reporters he “would be happy to come to Milwaukee, if we could get permission from the American League.” Three-quarters of the 12 American League clubs would need to approve the move.

However, the American League balked and required Seattle and the Pilots to work things out, partly by increasing the capacity of and making improvements to Sick’s Stadium. Starting construction of a domed stadium was required by the end of 1970, according to the initial agreement between the league and the team, but that did not seem to be going anywhere fast.

As the Pilots were making managerial changes in late November, the club hoped it found its new owner in a group led by local businessman Fred Danz, whose majority control would be decided upon by the American League owners in December. Not yet receiving approval, Danz met with new mayor Wes Uhlman and agreed to provide the city with a $600,000 letter of credit and $150,000 performance bond. There was a glitch, though: The money that Danz had hoped to receive to purchase the franchise was not forthcoming, and Daley and the Soriano brothers would remain in charge. Needing to raise $3.5 million to remain afloat, the team was given until Jan. 22, 1970, by the American League to make good on its finances. Missing the deadline, Mayor Uhlman threatened legal action if the Pilots left Seattle; Mayor Tommy Vandergriff of Arlington, Texas, offered to expand and upgrade minor league Turnpike Stadium to bring it up to major league specifications; and Hunt continued to seek the franchise.

All the while, Bud Selig and his Milwaukee investors remained in waiting, as the status of the Pilots was up in the air.

In February, as the Pilots players and baseball operations staff prepared to descend upon Tempe, Ariz., for Spring Training, the American League decided to keep the club under its current ownership and advanced it $650,000. Roy Hamey, former general manager of the Yankees, was selected by the American League to oversee the Pilots, though Milkes would remain in his role as general manager.

Seattle’s ticket sales were not going as well as club officials hoped they would, yet Milkes said the notion of a potential Milwaukee move were “absolutely ridiculous.”

Tommy Harper, entering his ninth season in the majors and owner of a league-leading 73 stolen bases for the Pilots in 1969, said players do feel the effects of such uncertainty.

“Certainly we’re aware of the financial problem,” he told the Chicago Defender. “It’s like an employer being in trouble, the employees have to be a little disturbed.”

Harper also wished the team would get a bit of good news from the press.

“Just because we’re a last place team, [the press doesn’t] come around,” he lamented. “We need the publicity. I mean good publicity, we’ve had enough of the other kind.”

Some good news came the next week in the form that the Pilots owners reached an agreement where the Milwaukee group headed by Selig and Judge Robert Cannon would purchase Seattle for $9.5 million. The franchise would shift to Wisconsin for the 1970 season.

The state of Washington and the city of Seattle, however, dampened the enthusiasm by filing a temporary restraining order, preventing the sale and the move of the franchise. By mid-March, the team even lost the ability to use its training facility, having “failed to comply with the agreements for use of the facilities.” The facility’s owner ended up allowing day-to-day usage, even though the club was behind $500,000 to the facility.

On March 19, citing debts of $7.4 million, the Pilots’ owners requested the team be sold to Milwaukee under the provisions of the Bankruptcy Act. Six days later, a referee in a federal bankruptcy court set aside the restraining order filed in King County, Wash.

As Pilots players scrambled to make living arrangements in Milwaukee and the team’s equipment remained in limbo – it had been scheduled to go to Seattle, the matter remained the courts until the evening of March 31, when the bankruptcy court ruled that Daley and the Soriano brothers could sell their franchise to Selig’s Milwaukee group for $10.8 million. The purchase agreement signed by the Milwaukee investors on March 8 would have expired at 10 am on April 1.

Citing the community’s response to the Brewers’ arrival as “absolutely staggering,” Selig felt the “feeling has been almost unbelievable. I truly believe the country will see something here that is very, very interesting to watch.”

Opening Day, scheduled for April 7, would remain in place, just at County Stadium instead of Sick’s Stadium.

Fans lined up for season tickets – over 1,000 were sold on the first day of sales.

“The response has not let up – and it’s even more today,” Selig said.

Several members of the team’s front office personnel also made the move. Milkes remained in place as general manager through the 1970 season. Gabe Paul, Jr., also came from Seattle to handle stadium operations in Milwaukee. Bristol would continue as manager.

Even Daley moved with the club. On April 5, the Brewers announced the names of the team’s seven new investors – and his name was among those on the list.

However, Selig remained at the forefront and would continue to do so until 1998, when he sold his stakes in the club in order to become Commissioner of Baseball on a full-time basis.

The Brewers finished only one game better than the Pilots did in 1969, but it was good enough for fourth place instead of last. The team also drew over 150,000 more fans to County Stadium than the Pilots did to Sick’s Stadium. Three years later, they surpassed the one million mark.

Thanks to the efforts of Selig and later ownership groups, 47 years later and now playing at Miller Park, the Brewers remain a Milwaukee icon.

Joe Schultz's stint with the Seattle Pilots was his first year as a manager. He would return to the big leagues in 1973 as skipper of the Detroit Tigers. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

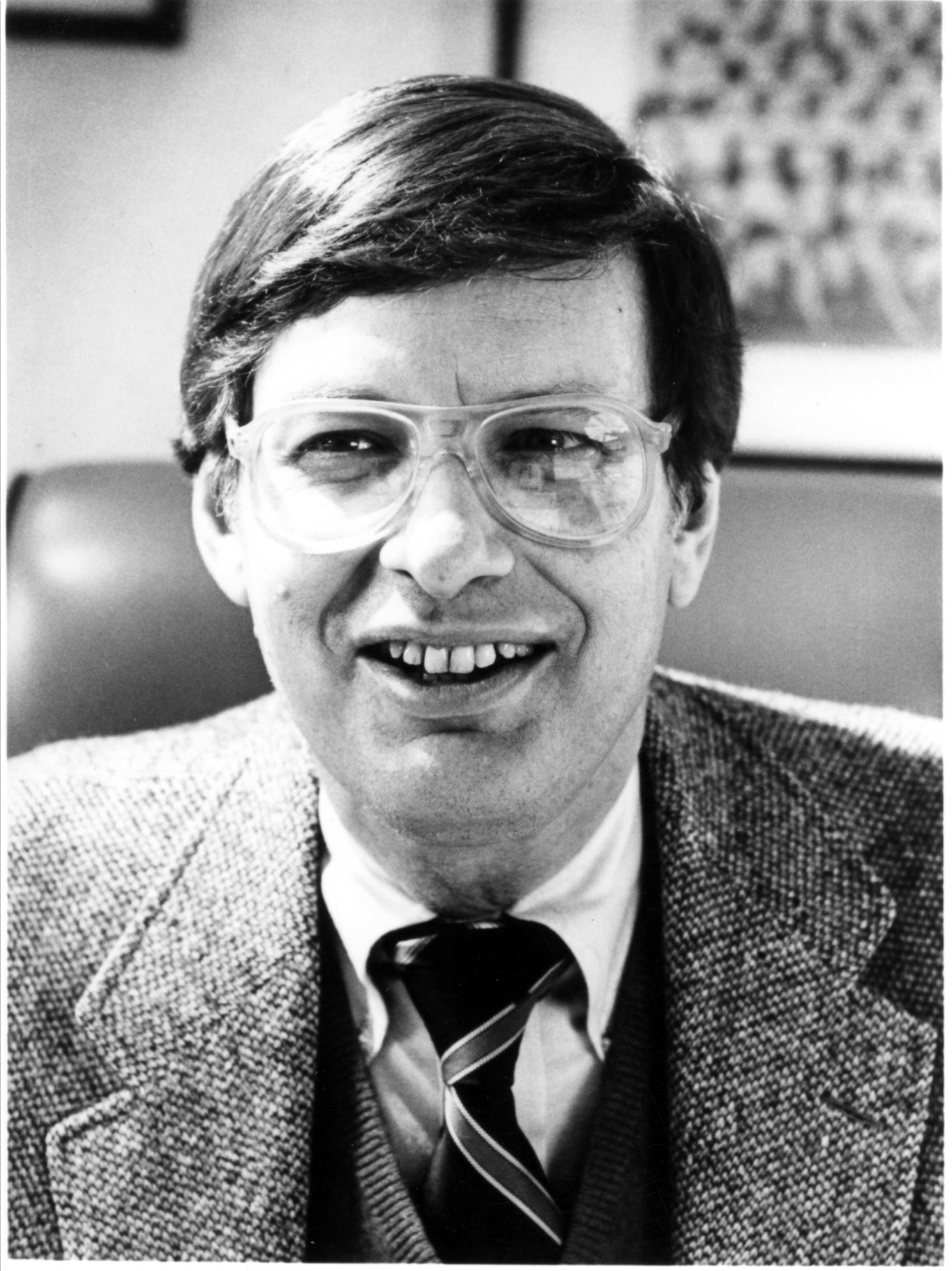

Bud Selig and other investors created Milwaukee Brewers Baseball Club, Inc. in 1966 to bring an expansion franchise to Milwaukee. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Tommy Harper led the American League in stolen bases in 1969 for the Pilots, with 73. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

A Seattle Pilots jersey belonging to outfielder Steve Hovley. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

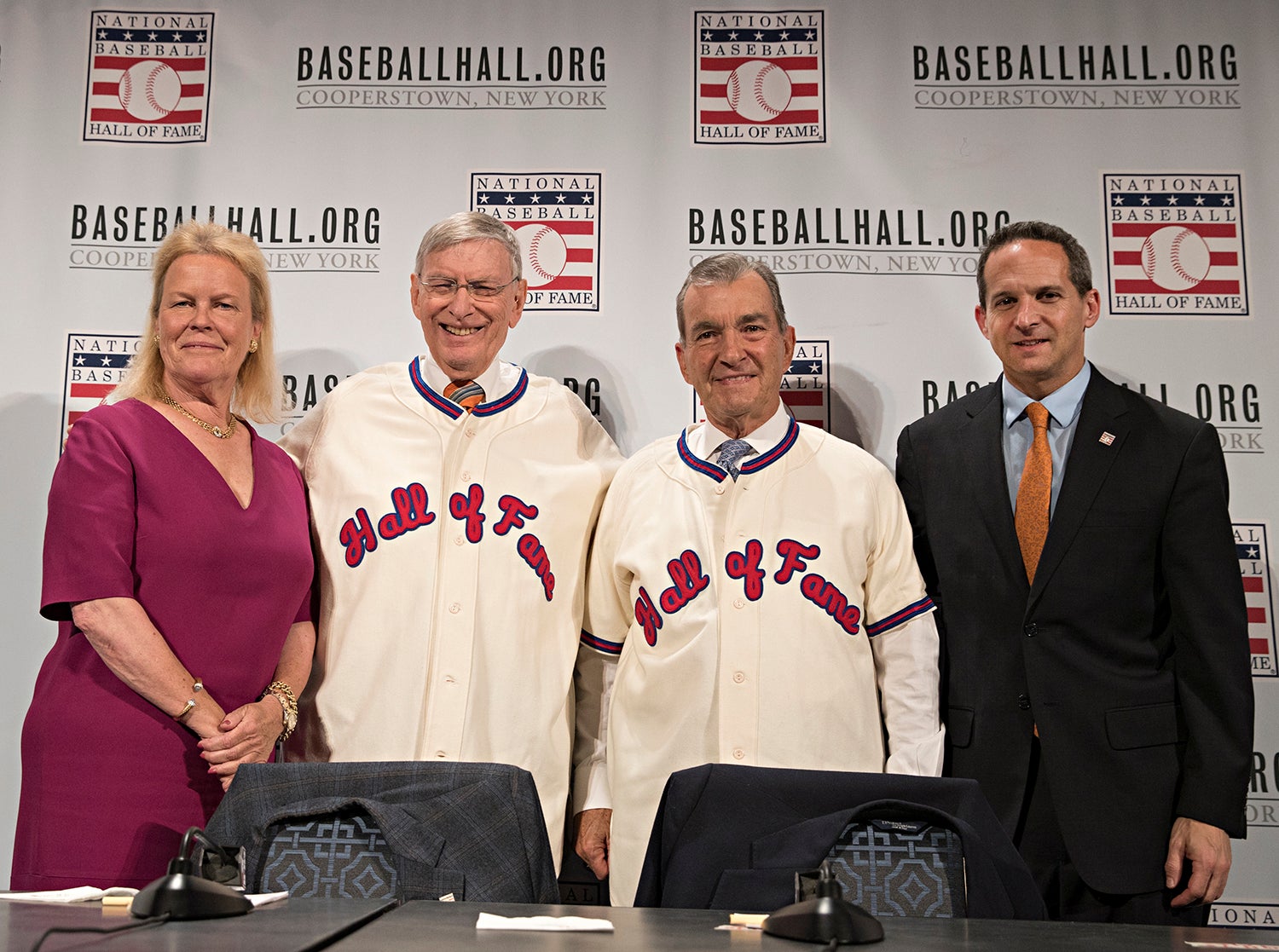

Bud Selig helped facilitate the move of the Seattle Pilots to Milwaukee, where they became the Brewers. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Matt Rothenberg was the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Schuerholz, Selig overwhelmed by honor of HOF election

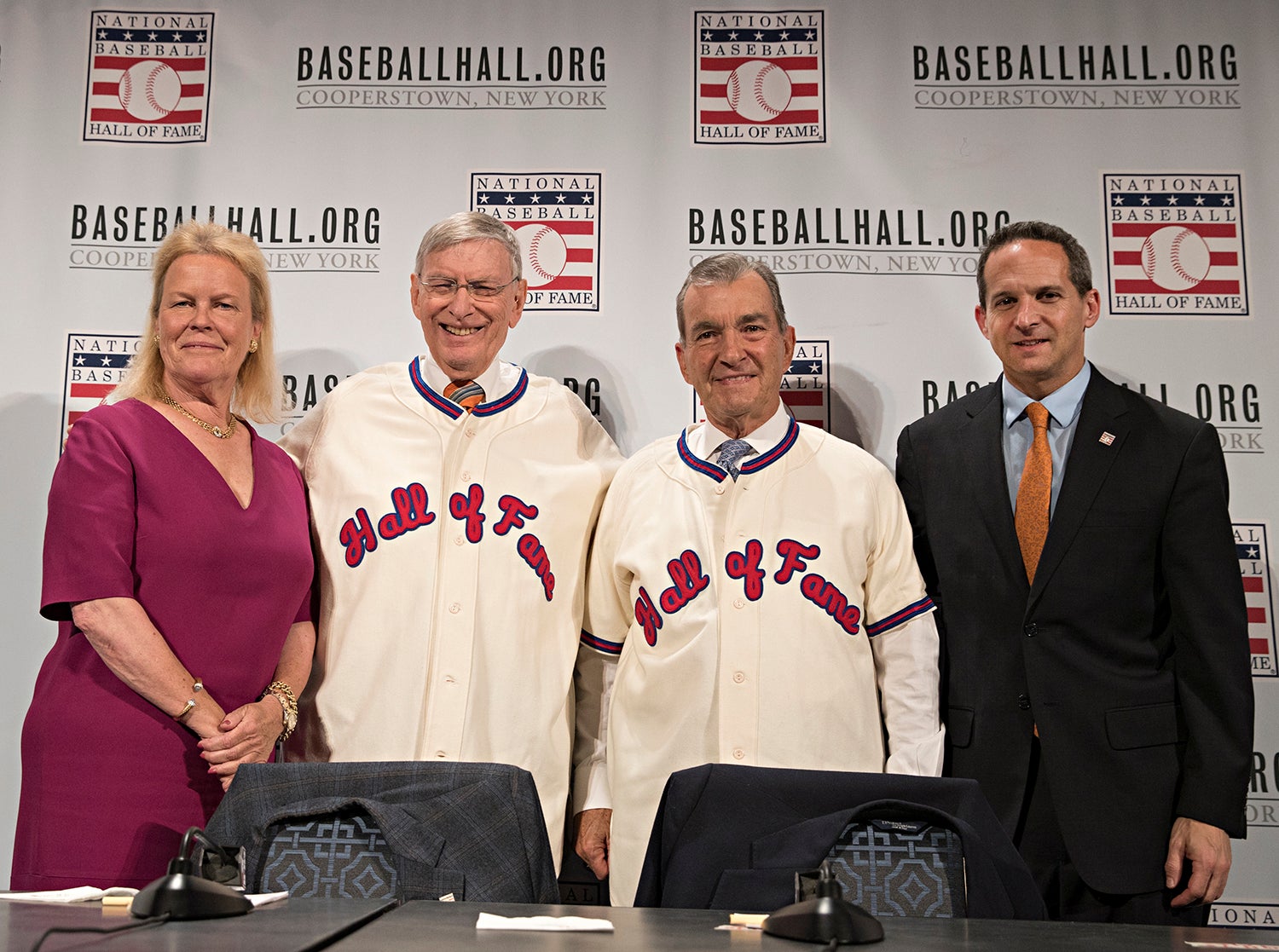

Schuerholz, Selig meet the media as Hall of Famers

Hall of Fame Weekend 2017 to Feature Inductions of Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines, Iván Rodríguez, John Schuerholz, Bud Selig, July 28-31 in Cooperstown

Schuerholz, Selig overwhelmed by honor of HOF election

Schuerholz, Selig meet the media as Hall of Famers