- Home

- Our Stories

- From One Robinson to Another

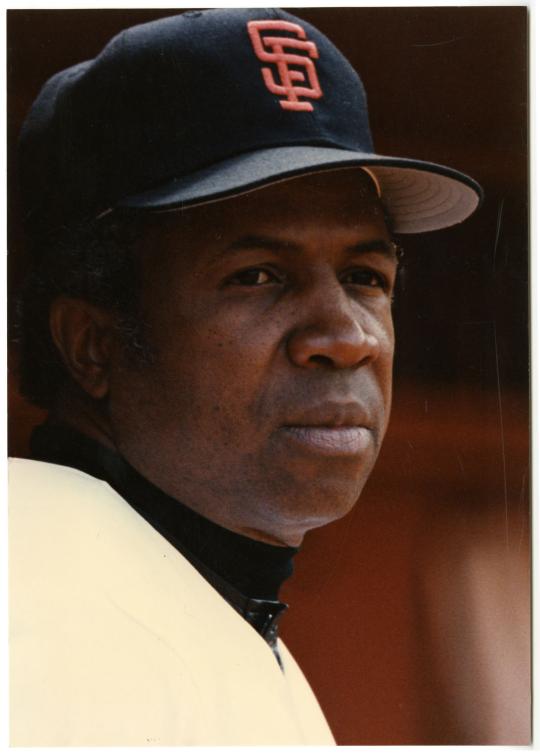

From One Robinson to Another

Before the season opener on April 8, 1975, Cleveland’s manager penciled an aging designated hitter into the second spot in the batting order. Showing he still had some pop left in his bat, the DH homered in his first at bat in the bottom of the first inning, making his manager look like a genius.

In this case, though, the manager and the hitter were the same person.

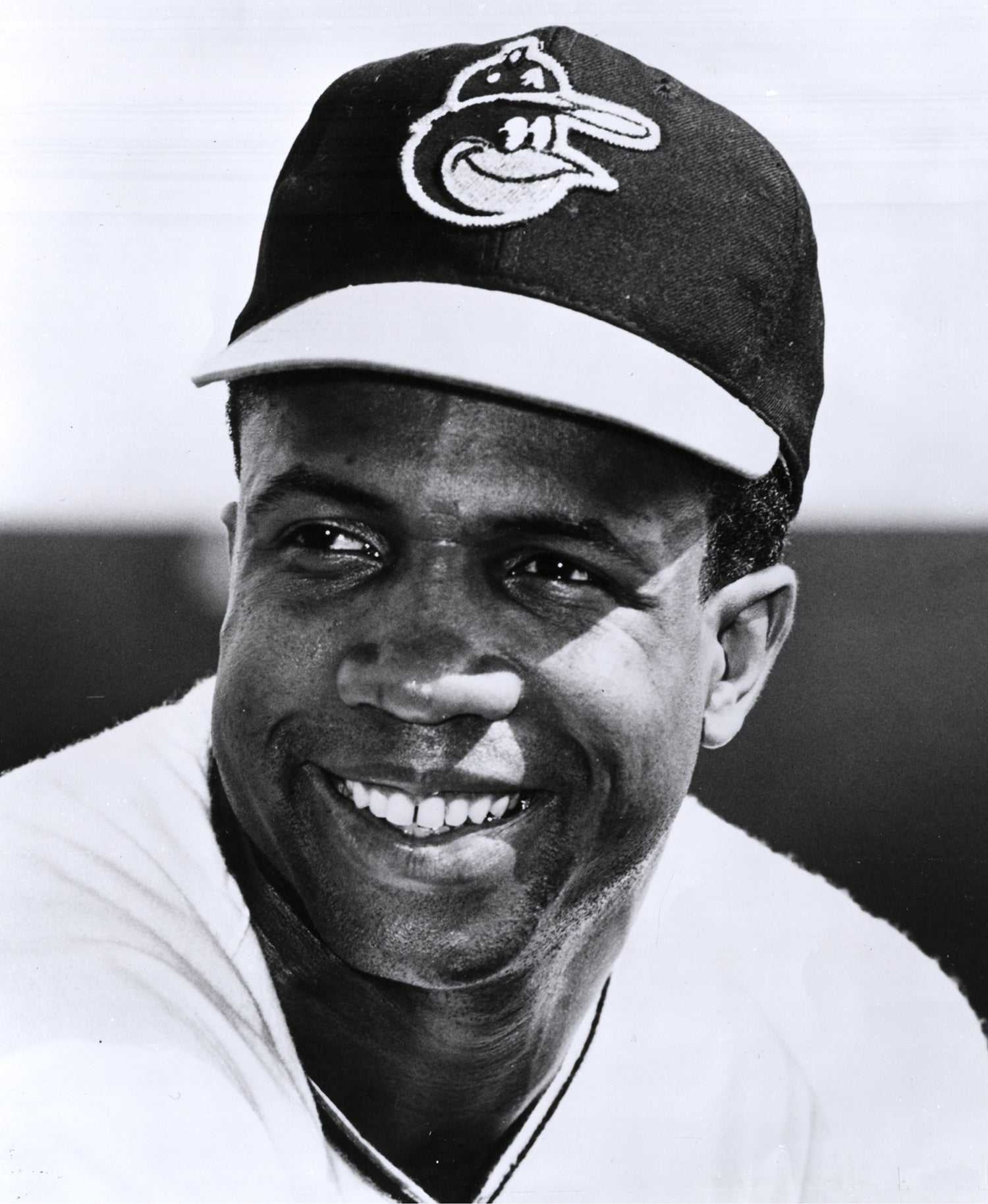

That afternoon at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland – 40 years ago – Major League Baseball history was made, as Frank Robinson managed his first regular season game, the first African American to do so. Robinson also contributed on offense to his first win, a 5-3 victory over the Yankees.

It was only a few years earlier, at Game 2 of the 1972 World Series, when the legendary Jackie Robinson – who himself took down one of baseball’s racial barriers – expressed his desire to see an African American managing a Major League Baseball team.

“I am extremely proud and pleased,” the ailing former Dodger said, over 25 years after his debut. “But I will be more pleased the day I can look over at the third base line and see a black man as manager.”

Unfortunately, he would never see that day. Jackie Robinson died shortly after the World Series that year, but his wife, Rachel, made the trip to Cleveland in 1975 to witness history.

Frank Robinson was well aware of Jackie’s influence on and importance to baseball.

“I thank the Lord that Jackie Robinson was the man he was in that position,” Frank Robinson said at his introductory press conference in October 1974. “The one wish I could have is that Jackie Robinson could be here today to see this happen.”

A Baseball Life

Born on Aug. 31, 1935 in Beaumont, Texas, Frank Robinson grew up in Oakland, Calif. The Cincinnati Reds signed Robinson prior to the 1953 season, and he broke into the majors in 1956 with one of the best rookie campaigns in history.

The 1956 season saw Robinson hit .290 with 38 home runs and 83 RBI, and he led the National League in runs scored (122) and times hit by a pitch (20). He was named to the All-Star Game and was the unanimous selection for Rookie of the Year.

The next nine seasons in Cincinnati saw five more all-star selections, a Gold Glove Award, and the 1961 National League MVP award.

Dealt to Baltimore in 1965, Robinson continued to shine. Named to five more all-star teams as an Oriole, Robinson’s 1966 season earned him a Triple Crown and the American League MVP award. He was the first to be named MVP in both leagues. Robinson also earned two World Series rings and was the MVP of the 1966 Fall Classic.

A future in management

Robinson would spend brief stints with Los Angeles and California. On Sept. 12, 1974, Robinson, by now primarily a designated hitter, was sold by the Angels to the Cleveland Indians for the $20,000 waiver price.

At the time of the deal, Indians general manager Phil Seghi stated that Robinson would be coming to Cleveland to play and not to be a potential replacement for manager Ken Aspromonte.

After the trade, Robinson was coy with reporters in his aspirations to manage in the major leagues. “I gave up the idea, but not the hope, and now I’m concentrating on being a player,” he said. “There is so much talk about hiring a black man to manage in the big leagues, but I don’t see anything being done about it.”

As the Indians limped to a middling 77-85 in 1974, Aspromonte was let go following the final game on Oct. 2. In three seasons, Aspromonte’s teams failed to reach .500, and although he had some decent talent in the clubhouse, he couldn’t put together a winning combination.

Rumors that Robinson would take over the team’s managerial role were in the wind for weeks. During the final days of the 1974 season, the Indians held negotiations with Robinson’s agent to make him the major leagues’ first African-American manager, and it was officially announced on Oct. 3 His contract would pay him at least $175,000, plus various fringe benefits, in 1975.

Robinson, who would continue to serve as a part-time designated hitter in 1975, rejected any notion that race play a role his new job and his performance in that job.

“The only reason I’m the first black manager is because I was born black. I’m not a superman; I’m not a miracle worker,” Robinson said. “This is what I really want to be judged by – the play on the field, and not on being the first, on being black.”

The Indians expected Robinson not only to be manager but to be a major part of the lineup, even though he was coming off a season where he hit .245 to go with 22 home runs and 68 RBI.

“I have great respect for Frank as a player. I know his average was not anything to rave about in 1974, but he was among the most productive hitters in the American League,” Seghi told reporters.

“Yes, I still believe Frank will be an important contributor to our offense. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t have signed him as a player-manager.”

Getting ready

Frank Robinson may have become the first African American to manage a Major League Baseball team when the Cleveland Indians named him their pilot, but Robinson had already logged many flight hours in the pilot’s seat. In fact, Robinson had long been considered a candidate to be the first African American manager in the major leagues.

In 1968, Earl Weaver became the new manager of the Orioles, but one of Weaver’s offseason roles was manager of the Santurce Crabbers in the Puerto Rican winter league. Robinson, still an active major leaguer, stepped into Weaver’s shoes in that role for the next several years, winning two Puerto Rican league titles along the way.

During his winters in Santurce, Robinson had the opportunity to manage several future Hall of Famers, including Jim Palmer, Reggie Jackson, Orlando Cepeda, and Robin Yount.

When a general manager suggested that Robinson manage in the minor leagues, instead of Puerto Rico, in preparation for a major league managing job, he scoffed at the notion.

“I think this is a better experience managing. I’m not guaranteeing I’ll be a great manager because until a man gets to the majors, no matter what he’s done, you can’t be sure. But the only advantage to managing in the minors is that you know the personnel of the organization,” Robinson noted to baseball writer Peter Gammons.

“Otherwise, here you deal with whites and blacks, Spanish-speaking players and English-speaking players, major leaguers, minor leaguers, high prospects and guys who won’t ever go anywhere. You certainly have motivational problems. And you have unique problems you don’t get in the minors.

“So I don’t buy that go-to-the minors business. Why should they tell a black man that when they don’t to a lot of whites?”

Yet in Puerto Rico prior to the 1974 Major League Baseball season, Robinson questioned his enthusiasm for managing.

“As a manager you have 25 individuals and your fate is in their hands. And I don’t know if I want that,” he said. “When you put together a lot of things that you see and don’t like, you start thinking, ‘Is this what I really want?’ I’m not really sure.

“I’m sure of only one thing. I’d never recommend managing to my son.”

In the morning before Cleveland’s 1975 opener, Seghi suggested that Robinson hit a home run in his first plate appearance.

Robinson’s reply was simple: “You’ve got to be kidding.”

But when Robinson took Doc Medich’s low and away fastball into the seats in the first inning, it made the day even more special for the new skipper.

“Any home run is a thrill, but I’ve got to admit, this one was a bigger thrill,” Robinson acknowledged after the game. He also admitted that the home run was “the single most satisfying thing that happened, other than winning the game.”

Despite Robinson’s home run, the Indians had to rally from a 3-1 deficit to win the game. Picking up the win was another future Hall of Famer, Gaylord Perry, who went the distance. Perry confronted Robinson during spring training with disagreements over the conditioning program but did not falter when the Yankees tried a comeback in the ninth inning.

“I couldn’t think of any better way to start my new career,” Robinson told reporters. “I was extremely pleased by the way we won. It was a team effort. The guys came from behind and played together and that’s what you have to do to be successful.”

Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow, was on hand and, during pre-game festivities, expressed her pride in Frank Robinson’s accomplishment. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and American League president Lee MacPhail were also present.

The 1975 Cleveland Indians finished 79-80, a slight improvement over the previous season, and in his second – and final – season as a player-manager, Robinson led them to an 81-78 mark in 1976. Solely focusing on his managerial duties for 1977, Robinson was led go after a 26-31 start and replaced by Jeff Torborg.

More jobs to come

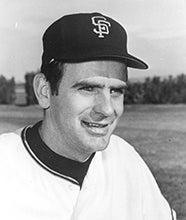

Frank Robinson would resurface in 1981 as manager of the San Francisco Giants, spending just short of four seasons there before being fired. Rejoining the Orioles as a coach, he took over as manager for Cal Ripken, Sr., in 1988, six games into their season-opening 21-game losing streak. Robinson brought the O’s over .500 in 1989, earning AL Manager of the Year honors, but the team regressed in subsequent seasons, prompting a move to the front office.

Working for Major League Baseball, Robinson’s final managerial appointment occurred in 2002 when he was selected to lead the Montreal Expos. Moving with the Expos to Washington in 2005, Robinson led the club in its first two seasons in the nation’s capital. After the 2006 season, Robinson retired from managing but remains involved with Major League Baseball.

In the 40 years since Frank Robinson’s managerial debut, more than half of the teams in Major League Baseball have hired African Americans as managers. Former Toronto skipper Cito Gaston was the first to lead a team into the playoffs and to a World Series championship.

Seattle’s Lloyd McClendon is the only African American manager in Major League Baseball at the start of the 2015 season.

Matt Rothenberg was the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum