- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball stars super at pitching products

Baseball stars super at pitching products

On Sunday, millions of Americans will gather around televisions to watch the Super Bowl, but many of those people will be more attuned to the action in between the coverage of the Patriots and Falcons.

Those folks are paying attention to the commercials – brief spots which command millions of dollars during the Super Bowl and also provide plenty of water cooler fodder the next day.

While Super Bowl ads might be the pinnacle of the industry, baseball is certainly no stranger to the world of advertising. Ad men were going mad promoting products using baseball and its stars long before the television show Mad Men glamorized the industry.

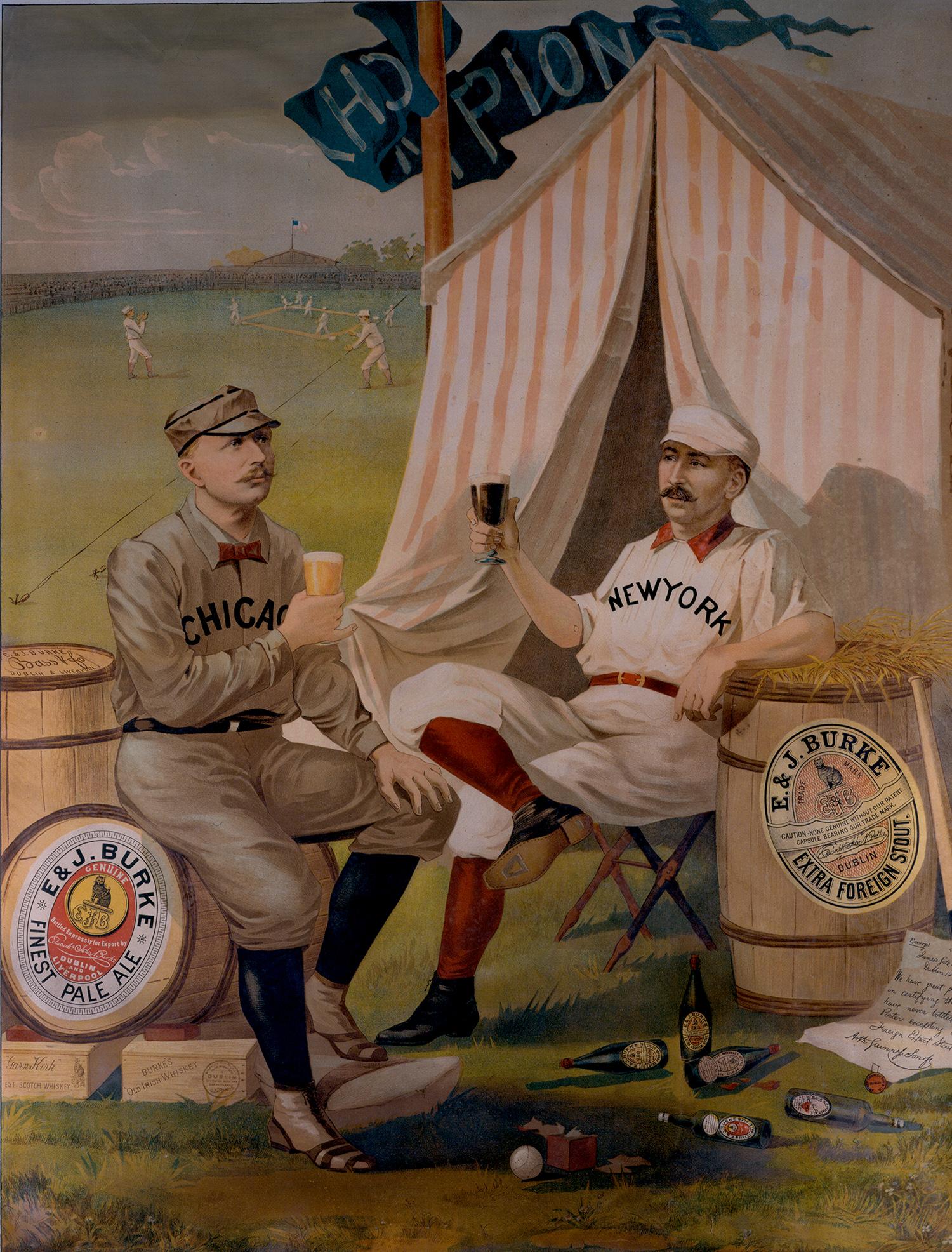

Before television, however, most of the advertising was found in print. An 1889 lithograph featuring Chicago’s Cap Anson and New York’s Buck Ewing quaffing glasses of beer from E. & J. Burke may be one of the earliest examples of ballplayers being paid to endorse a consumer product. Later print advertisements would depict Hall of Famers – and non-Hall of Famers – peddling everything from alcohol and tobacco products to cereal, cars, dog food, and men’s underwear.

As Americans began to consume more and more television in the mid-20th century, companies and advertising agencies began to realize the necessity to shift dollars from print to electronic media. Recognizable individuals such as major league ballplayers provided companies familiar faces to promote their products. Naturally, some advertisements were geared toward a player’s local market and others were shown to a broader, national audience.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum has discovered some of these spots in its audiovisual collection, often found between innings of recorded games.

Boston Red Sox slugger Carl Yastrzemski, for one, took a few seconds following batting practice to inform viewers of his choice in aftershaves.

“I’ve been playing major league ball for a lot of years. I’ve seen a lot of ballplayers come and go – and lots of aftershaves, too,” Yaz noted, later delivering the brand’s slogan. “I’ve always liked Aqua Velva. … Buy ’em all if you want to, but you’ll find out there really is something about an Aqua Velva man.”

Sometimes advertisers would play off the reputations of ballplayers. Panasonic did just that with Reggie Jackson, known to have had a particular level of ego during his playing days. The ad – one of several Jackson appeared in for Panasonic – begins with a woman saying, “No ego, Reggie? What’s this?” as she opens a refrigerator to find a television featuring Jackson at bat. She then uncovers televisions in a medicine cabinet, in the bedroom ceiling, and behind curtains, all of which feature Jackson on the screen.

“Only Panasonic plays as brilliantly as I do,” Jackson says when asked why he has all the TVs.

Jackson's former team, the New York Yankees, also played to his reputation. When the ballplayer famously said "If I played in New York,'' he said, ''they'd name a candy bar for me," the New York Yankees decided to shower fans with 72,000 Reggie! bars, for the home-opener of Jackson's second season with the Yankees.

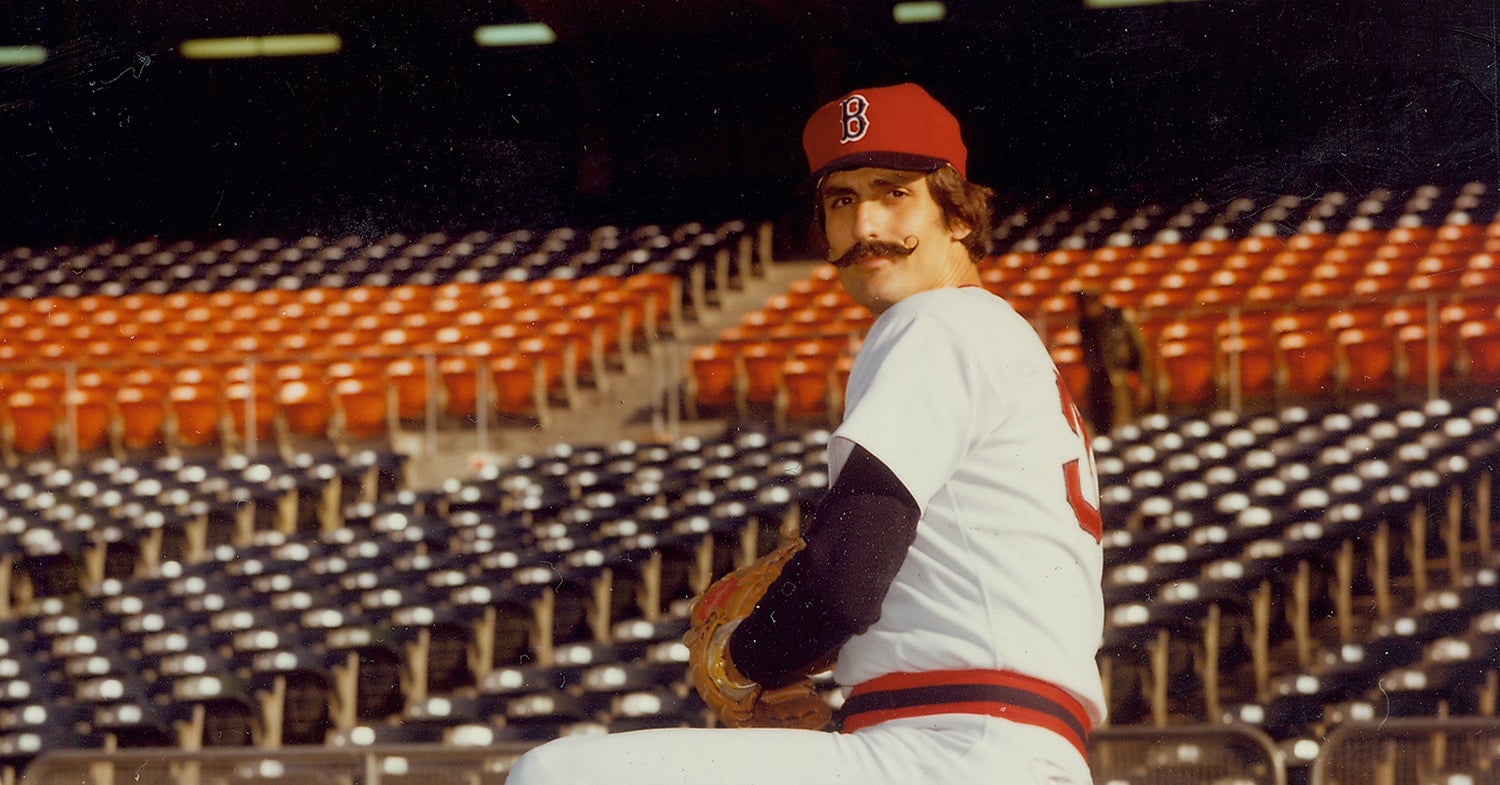

Often the television or radio station which hosted a team’s games might use that team or its players for advertisements. Such was the case for 760 KFMB in San Diego, once the longtime radio home of the Padres. Station personalities Mac Hudson and Joe Bauer are featured “coaching” Padres pitchers Rollie Fingers and Randy Jones.

When asked what their favorite morning team is, Fingers incorrectly answers the Padres, while Jones responds with bacon and eggs. The answer, of course, should have been Hudson and Bauer, a popular morning-drive radio team in San Diego.

Miller Brewing Company first sold its Miller Lite beer in 1973, and from the start, its advertisements featured professional athletes and other personalities, including many associated with baseball.

One spot features Frank Robinson and Brooks Robinson, teammates with the Orioles from 1966 through 1971.

The Robinsons share the number of ways in which they are similar, as well as the reasons they drink Miller Lite, but Brooks cautions viewers, saying “I know we’re incredibly alike, but don’t be confused. We are not identical twins.” This prompts Frank to crack up on camera, trying to say, through laughs, “I’m at least two inches taller than he is.”

Cubs reliever Bruce Sutter and Phillies third baseman Mike Schmidt appeared in the same commercial for 7-Up soda, announcing that “America’s turning 7-Up.” In one scene, after Schmidt taps his bat on home plate, the plate rises and out of the ground comes a bottle of 7-Up. Bloopers from the making of this ad show the number of failed takes it took before there was success in the mechanism working. Gary Carter did an appearance in a Canadian version of the 7-Up ad.

Not only do Hall of Famers appear in TV commercials for comestibles, but they also relate that they share the pain viewers feel and know how to best overcome it. At the end of his career, Nolan Ryan is seen working out but told the audience that Advil helps him relieve pain. George Brett promoted Ben Gay, which helped him relieve bouts of arthritis. Bob Gibson heralded the benefits of Primatene Mist bronchial spray and Primatene tablets.

Some Hall of Famers promoted various products. Ken Griffey, Jr., was a pitchman for Nike, Pizza Hut, Pepsi, and Visa. Johnny Bench once did a spot for the Yellow Pages and, more recently, has become a spokesman for Blue-Emu cream.

Baseball Hall of Famers have also been known to help networks promote programming. In one of numerous ESPN SportsCenter commercials featuring current and potential Hall of Famers, ESPN personalities are discovering a trail of petroleum jelly as Gaylord Perry walks through the network’s offices. Another ad has Derek Jeter discovering green fuzz in his razor. He asks around the ESPN locker room to see who has used his razor, receiving denials before the Phillie Phanatic walks through wrapped in a towel.

Hall of Famers also provide a voice of concern during public service announcements. Hank Aaron made one for the Boy Scouts of America, while the Institute of Makers of Explosives had Willie Mays tell kids about the dangers of playing around with blasting caps.

“You protect your arms and hands and legs and save your eyes,” Mays warns children during a road game. “If you see a blasting cap – remember now – don’t touch them. Tell the police, a fireman, whatever it is. Have fun, like I do with [baseball equipment], not [blasting caps].”

Whether being warned to avoid handling explosives or being convinced to drink light beer, baseball’s Hall of Famers have long been a source of recognition when companies and advertising agencies need someone to promote a product or foster a cause. Though many may never hurled a ball from the mound, they have certainly perfected the art of pitching.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Frank Robinson Traded to Orioles

Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox

Bob Gibson wills Cardinals to Game 7 victory in 1964 World Series

Frank Robinson Traded to Orioles

Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox