- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball awards date back to game’s earliest days

Baseball awards date back to game’s earliest days

Bellinger vs. Yelich. Williams vs. DiMaggio. Cobb vs. Lajoie.

There is no more time-honored tradition among baseball fans than arguing over the most deserving award winners at the end of every season.

For more than a century, that debate has largely centered around who's considered the Most Valuable Player in each league. The roots of the MVP award, baseball's oldest and most prestigious individual honor, date back to the late 1800s.

Today, there are more awards than ever – many of them named after celebrated award winners of the past – rewarding modern players for their accomplishments both on and off the field. Major Leaguers may receive contract bonuses and shiny Tiffany trophies when they win awards, but more importantly, they earn a permanent place among the game's storied greats.

These MLB awards, from the Cy Young Award to the Fred Hutchinson Award to the Tony Gwynn Award, all have their own unique histories, too. Some are famous or controversial, with the results debated by fans for months and years afterward. Others hold special meaning for players who may never receive one of the “major” awards.

But no award has evoked more controversy, or has a more interesting backstory, than the MVP award.

The idea of honoring the player who was most valuable to his team's success goes back at least to 1875, one year before the formation of the National League. That season, future Hall of Fame catcher Jim “Deacon” White batted .355 in leading the Boston Red Stockings to a 71-8 record in the old National Association. As historian Bill Deane documented in "Total Baseball", White was presented with a tray of silver inscribed “Most Valuable Player to Boston Team” from an admiring fan.

Fans in other cities, however, did not pick up on the tradition. So White's hardware was a one-time honor. It took another generation before that type of award returned to prominence. And if not for a scandal involving two Hall of Famers, the MVP award as we know it might not exist today.

Ty Cobb drives the Chalmers automobile around Shibe Park that he won for his performance during the 1910 season. In the car with Cobb is Hugh Chalmers, donor of the automobile. The Chalmers Award was one of the first examples of an MVP award in baseball. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In 1910, automobile executive Hugh Chalmers announced that he would present one of his company's new roadsters to the player with the highest batting average that season. A two-man race between Detroit's Ty Cobb and Cleveland's Napoleon Lajoie came down to the last day. Lajoie came out on top, .384 to .383, only because of a remarkable 8-for-8 performance in the final doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns. It was later discovered that Browns manager Jack O'Connor had instructed his rookie third baseman, Red Corriden, to play back in short left field and allow Lajoie to easily bunt for singles all day long.

A public relations disaster ensued and, after the dust had settled, Cobb was declared the winner by American League president Ban Johnson (who discovered a “discrepancy” in the record books and awarded two extra hits to the Tigers star) and O'Connor was kicked out of baseball.

Chalmers decided to award cars to both Cobb and Lajoie in a gesture of goodwill. The next season, despite calls from some baseball writers to abolish the concept of individual awards entirely, the automaker suggested new criteria for his prize. He would award an automobile to one player in each league who was “the most important and most useful player to his club and to the league at large in point of deportment and value of services rendered.” This was the first modern MVP award, selected by a committee of 16 writers, one from each city in the league.

Cobb took home the first Chalmers Award (as it was known) in 1911 for the AL, while Chicago Cubs outfielder Frank “Wildfire” Schulte won in the NL. But fan interest in the award quickly diminished, in part because Cobb voluntarily “retired” from winning it again the following year. By 1915, the Chalmers Award became extinct.

This idea that a player could only win the MVP once helped doom the next attempt at establishing the award, too. The American League started awarding an MVP trophy in 1922 and the National League in 1924, but both were abolished by the end of the decade. Because he had already won the award in 1923, Babe Ruth's ineligibility to win the award after his record-setting 60-homer season in 1927 played a role in destroying its credibility.

Finally, in 1931, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America decided to standardize its voting process and the modern MVP award was born. This time, there was no limit to the number of times a player could win, player-managers were also eligible — and so too were pitchers.

Calls to exclude pitchers from the MVP had been heard since the beginning, but the BBWAA repeatedly asserted that all big league players were eligible. However, the perception among some writers and fans that no one who took the mound every fourth or fifth game could be as valuable as a position player persists to this day. Yet in the first five years of the award, Lefty Grove, Dizzy Dean, and Carl Hubbell all won the BBWAA vote. During World War II, American League pitchers Spud Chandler and Hal Newhouser (twice) captured three consecutive MVPs in 1943-45.

But pitchers winning the MVP turned out to be a rare occurrence and, in an effort to better honor baseball's top moundsmen, Commissioner Ford Frick led the way in establishing an award especially for them in 1956. It was named after the game's all-time winningest pitcher, Cy Young, who had recently died. Initially, only one Cy Young Award winner was chosen each year, but it was expanded to one pitcher in each league starting in 1967.

The Cy Young Award was not the first award to recognize a special category of players. In 1940, the BBWAA's Chicago chapter began voting for the top rookie of that season, with Lou Boudreau winning the first award. Baseball writers in other cities were added to the selection process in 1947 and the Rookie of the Year Award was created — named at the time after former White Sox owner J. Louis Comiskey, the son of team founder Charles Comiskey.

In 1987, the award was renamed after its first winner, Jackie Robinson, whose pioneering rookie season for the Brooklyn Dodgers 40 years earlier had broken the color barrier and changed the course of American history.

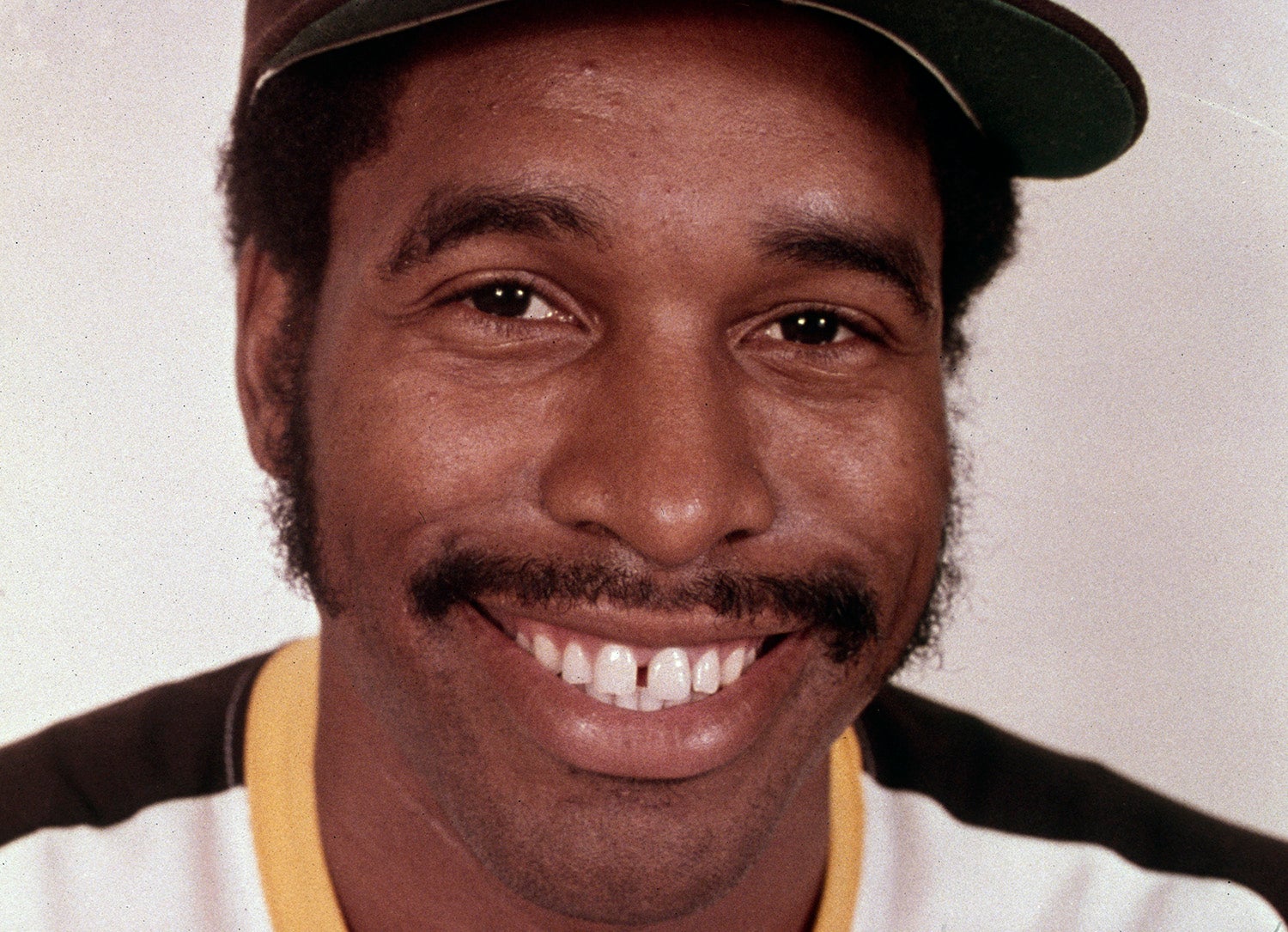

No player has ever won the big three – the MVP, Cy Young and Rookie of the Year – in the same season, although two pitchers have come close. Vida Blue of the Oakland A’s was 21 years old and in his first full season when he finished first in the AL’s MVP and Cy Young voting in 1971. But he was no longer eligible for the Rookie of the Year despite spending most of the previous two seasons in the minor leagues.

Ten years later, Fernando Valenzuela of the Los Angeles Dodgers took the baseball world by storm, winning his first eight starts (including five shutouts) to begin the 1981 season. He took home the Cy Young and Rookie of the Year awards, but finished fifth in the NL MVP voting.

Mike Trout smiles after accepting the 2015 All-Star Game Most Valuable Player trophy at Great American Ball Park in Cincinnati. Trout became the first player to win back-to-back All-Star Game MVPs, having won the 2014 award at Target Field in Minneapolis. The first All-Star Game MVP Awards were presented in 1962. (Jean Fruth/National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

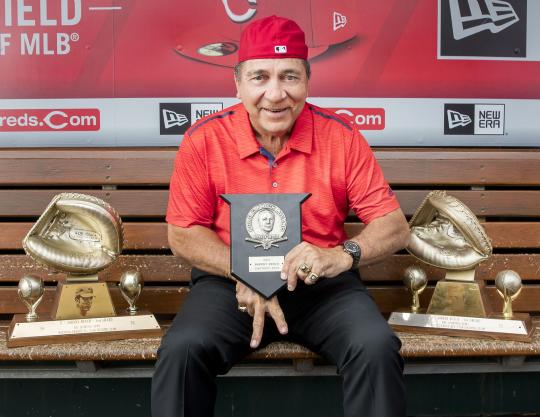

Over the years, other awards were created by corporate sponsors to celebrate specific achievements or excellence in a single area, such as the Rawlings Gold Glove Awards (1957) for the top-rated fielders at each position, the Rolaids Relief Man Awards (1976) for the best relief pitchers, and the Silver Slugger Award (1980) by Hillerich & Bradsby for the best offensive player at each position.

In 2014, the defunct Rolaids awards were replaced by MLB awards named after New York Yankees great Mariano Rivera and San Diego Padres record-setting closer Trevor Hoffman. This move continued a growing hardware trend: Many of baseball's current awards are now named after star players of the past.

For example, there's the Mel Ott Award (for the National League's home run leader), the Lou Brock Award (stolen-base champions), the Hank Aaron Award (top hitters in each league), the Edgar Martinez Award (top DH), the Ted Williams Award (MVP of the All-Star Game) and the Tony Gwynn and Rod Carew Awards (batting champions in each league).

Even some lesser-known ballplayers have prestigious awards named after them. The Tip O'Neill Award, whose namesake was a Triple Crown-winning outfielder in the 19th century, honors the top Canadian-born ballplayer in the major leagues. Meanwhile, the Fred Hutchinson Award was established in honor of the inspirational pennant-winning Cincinnati Reds manager who died of cancer at age 45.

Jacob Pomrenke is the Society for American Baseball Research's director of editorial content

Related Stories

White Sox second baseman Nellie Fox named '59 AL MVP

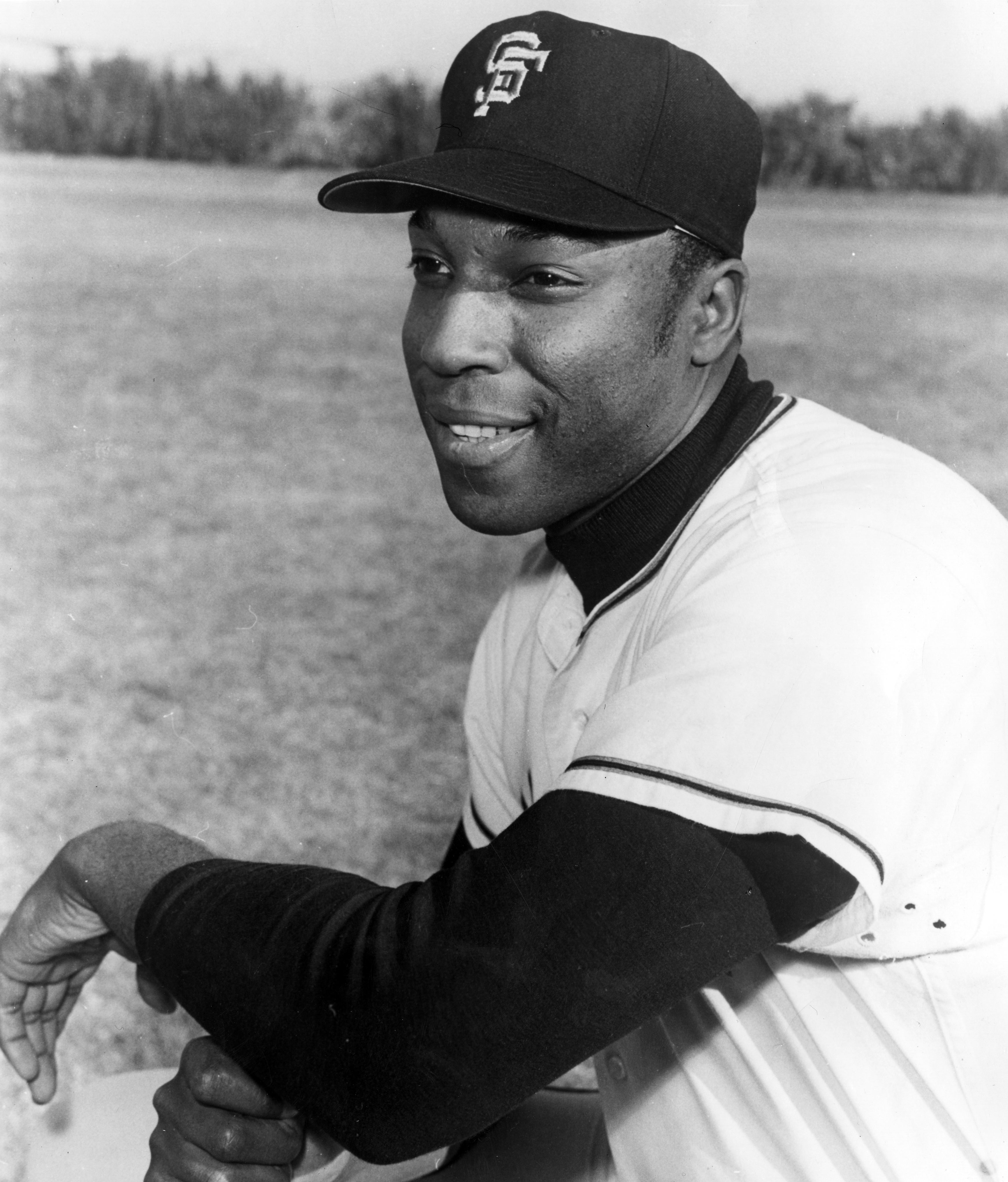

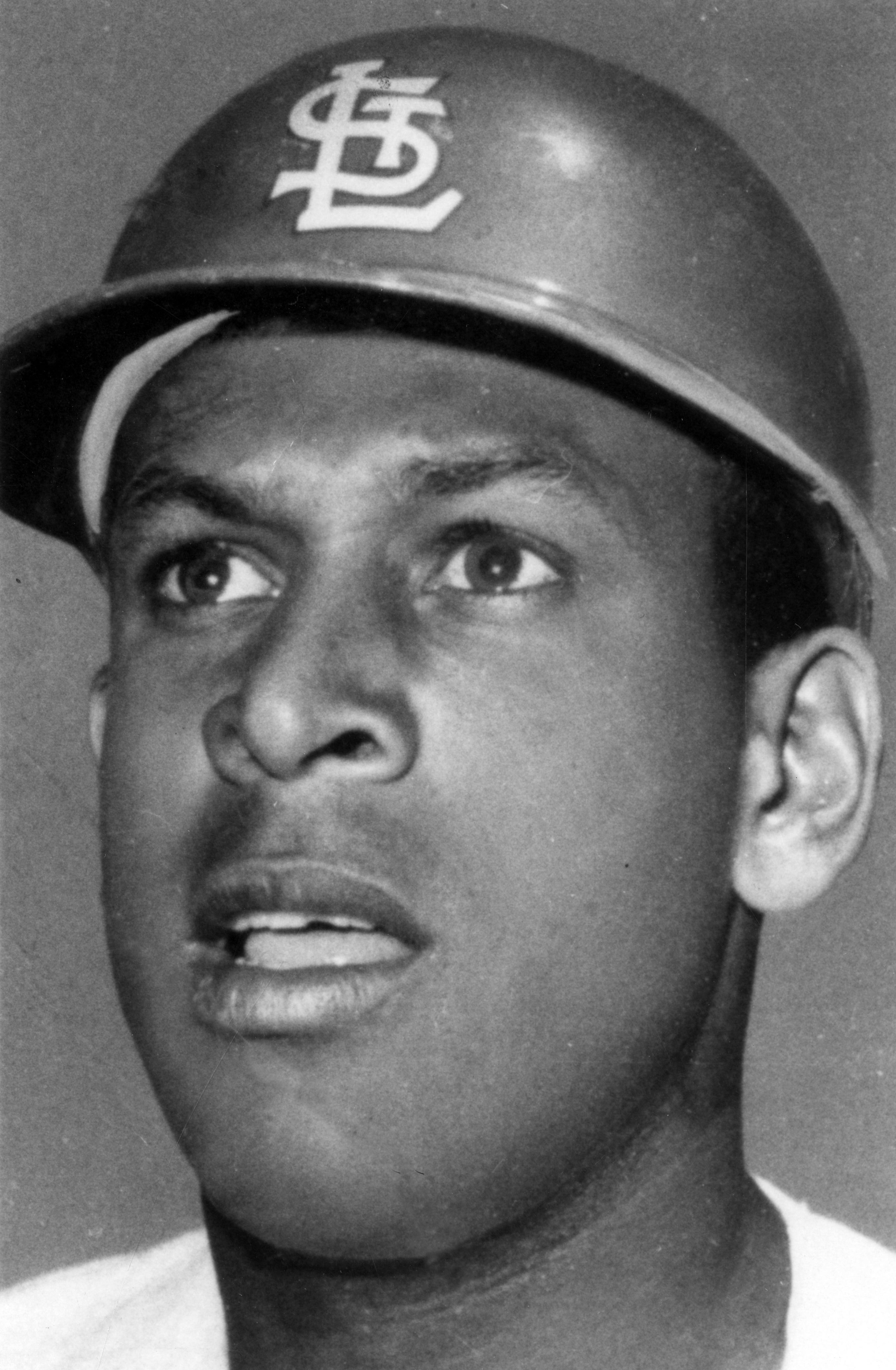

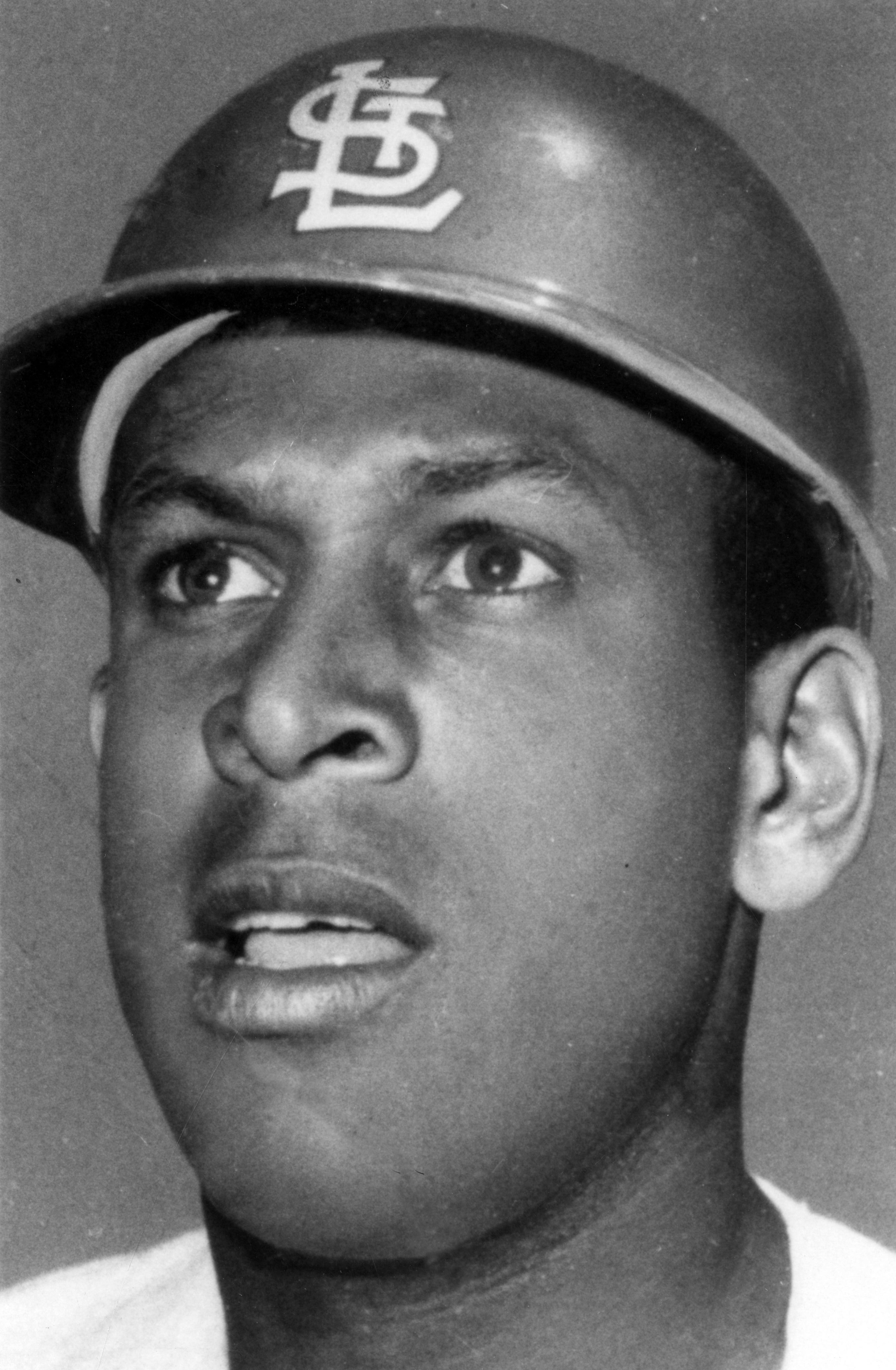

Cepeda caps comeback with unanimous NL MVP

Gaylord Perry's super '72 results in AL Cy Young Award

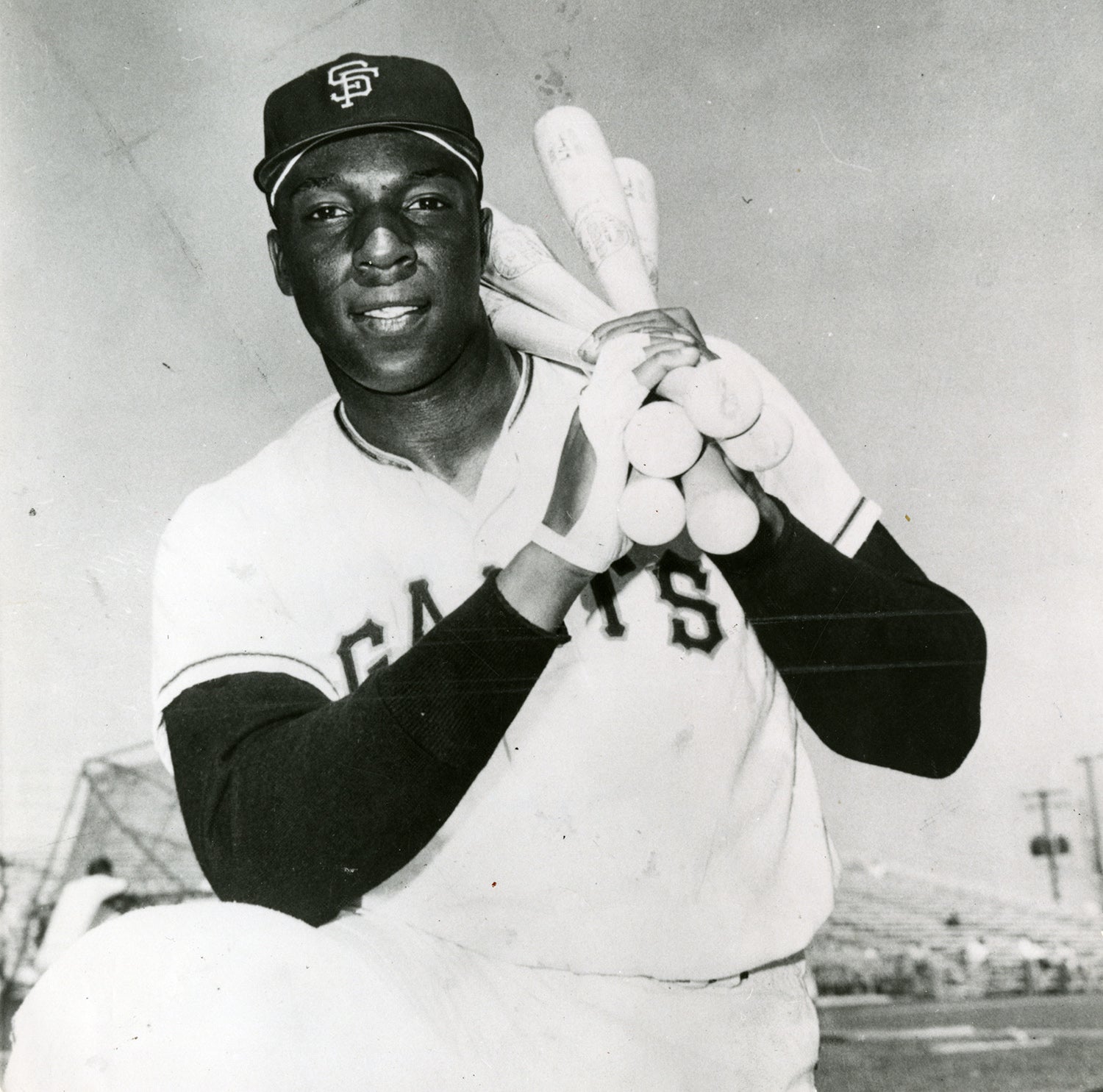

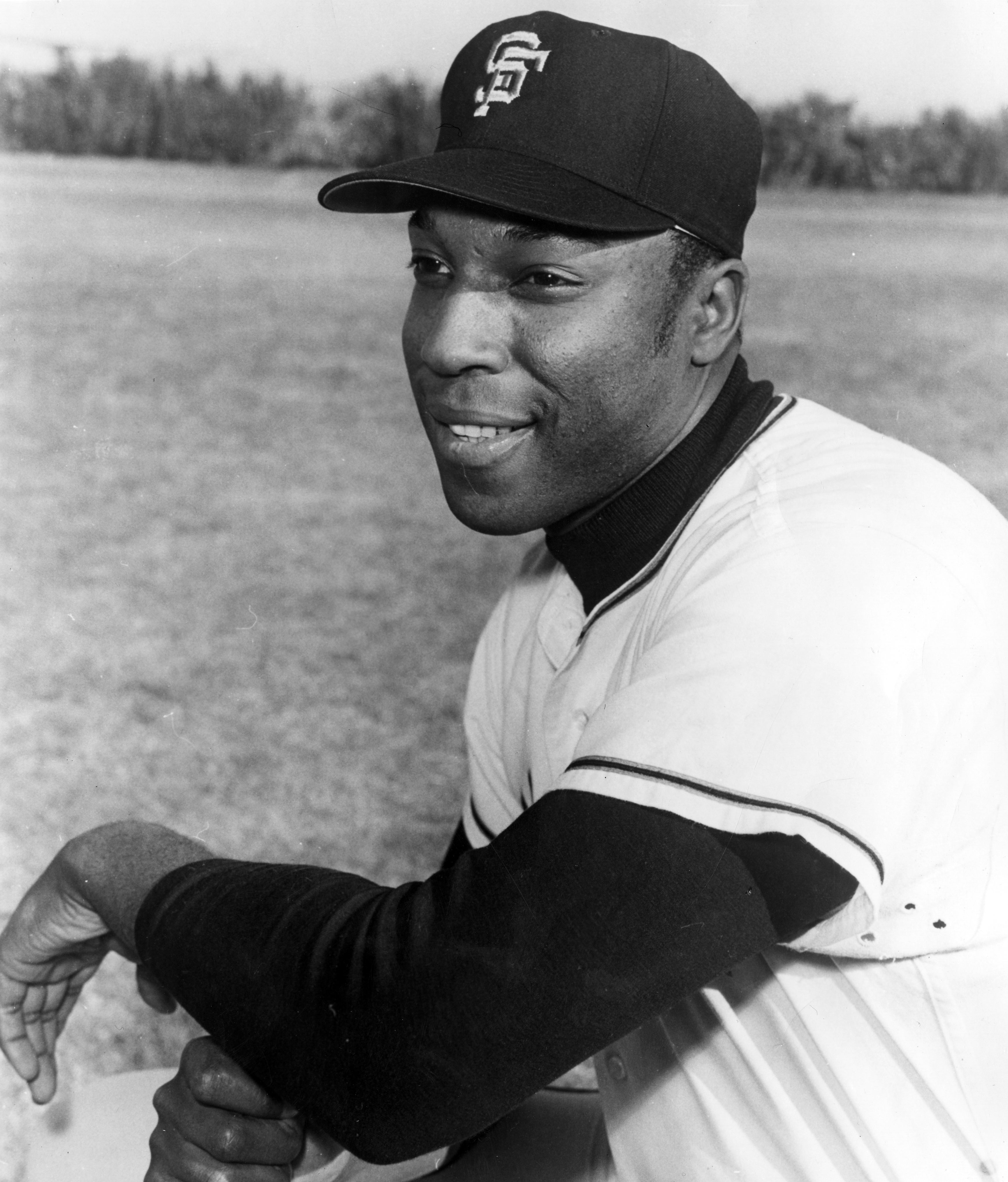

McCovey roars as rookie

White Sox second baseman Nellie Fox named '59 AL MVP

Cepeda caps comeback with unanimous NL MVP

Gaylord Perry's super '72 results in AL Cy Young Award