- Home

- Our Stories

- No minor achievement

No minor achievement

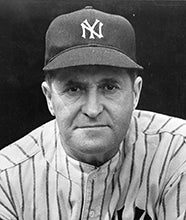

On Nov. 20, 1985, the struggling Pittsburgh Pirates, having just suffered through a 104-loss season under manager Chuck Tanner, named Jim Leyland their new skipper.

Leyland, 40, came with a glowing endorsement. From 1982-85 with the White Sox, he had served as third base coach under manager and fellow future Hall of Famer Tony La Russa.

“Leyland had been in the running for almost every managerial job that had opened since he became a hot item after the Chicago White Sox made it to the 1983 playoffs and manager Tony La Russa began telling the world what a sharp guy his third base coach was,” wrote the Pittsburgh Press.

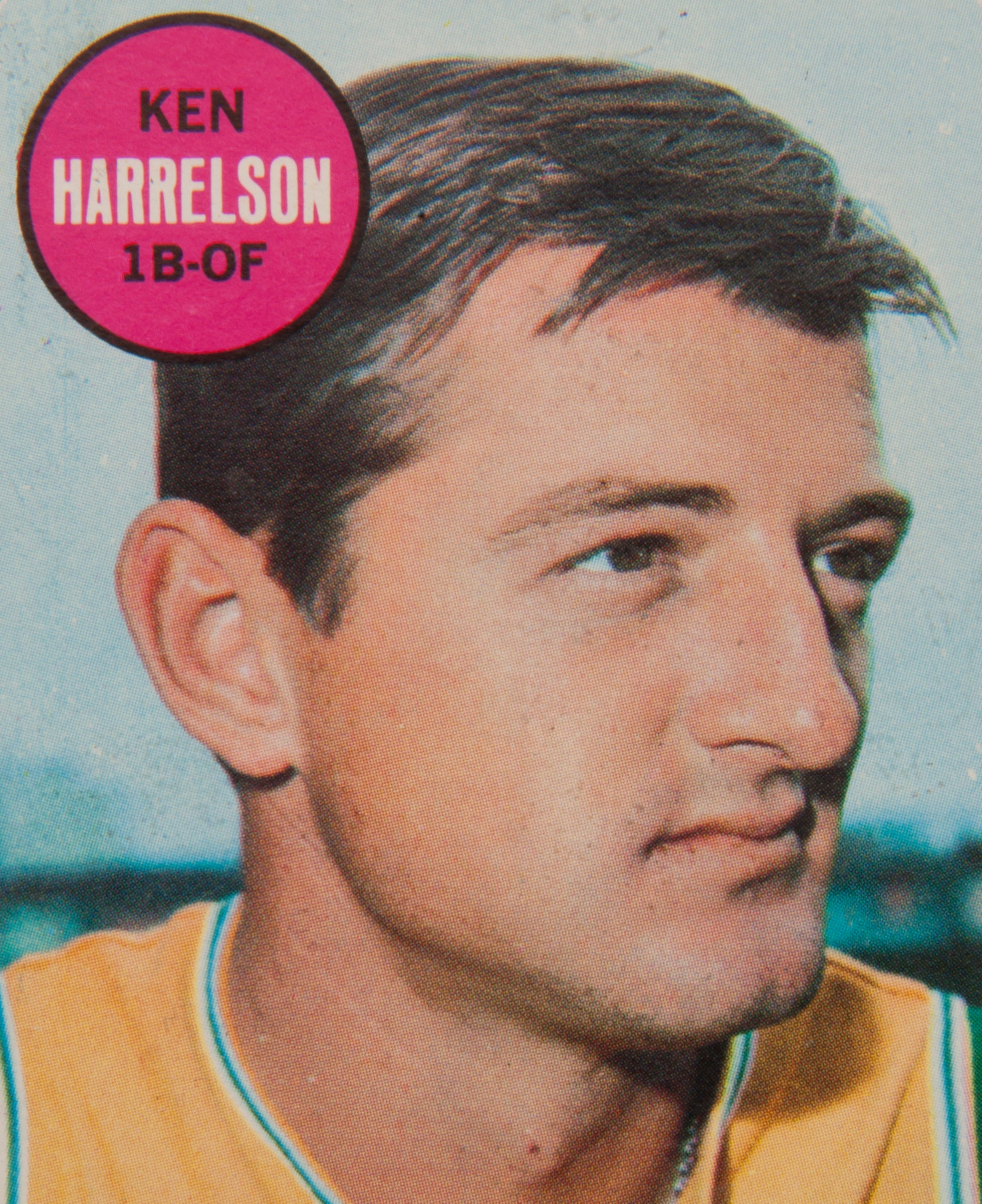

“It takes three things to become a successful manager — knowledge, patience and guts — and Leyland has a high degree of all three of them,” White Sox general manager Ken Harrelson, who’d later become a broadcaster and win the 2020 Ford C. Frick Award, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “If La Russa had decided not to return as our manager, Jim Leyland would be the White Sox manager today.”

Leyland boasted plenty of minor league coaching experience, but the four seasons in Chicago had been his only taste of the big leagues. The former catcher had played seven minor league seasons in the Tigers organization but never rose above Double-A, his offensive shortcomings putting a major league career out of reach. But Leyland proved to be extremely prepared for a coaching career.

“I was 26, had been a player-coach and was trying to make a decision if I wanted to stay with baseball,” Leyland told the Press. “Frank Carswell, who I played for at Montgomery, became ill. They (the Tigers) revamped their whole minor league system. They asked me if I was ready to try a club of my own. I wanted to try it.”

A decade-and-a-half later, Leyland had landed his first big league managing gig, albeit as an outlier among MLB skippers. Of the 24 men to manage at least 100 games in 1986, only Leyland and three others — John McNamara of the Red Sox, Ray Miller of the Twins and future Hall of Famer Earl Weaver of the Orioles — hadn’t played at the major league level. For context, in 2023, 21 of 30 managers were former MLB players.

And of the 23 skippers enshrined in Cooperstown, only four never got a cup of coffee as big league players. Those four men’s legendary managerial careers are well-documented, but how did they land their initial jobs in the first place?

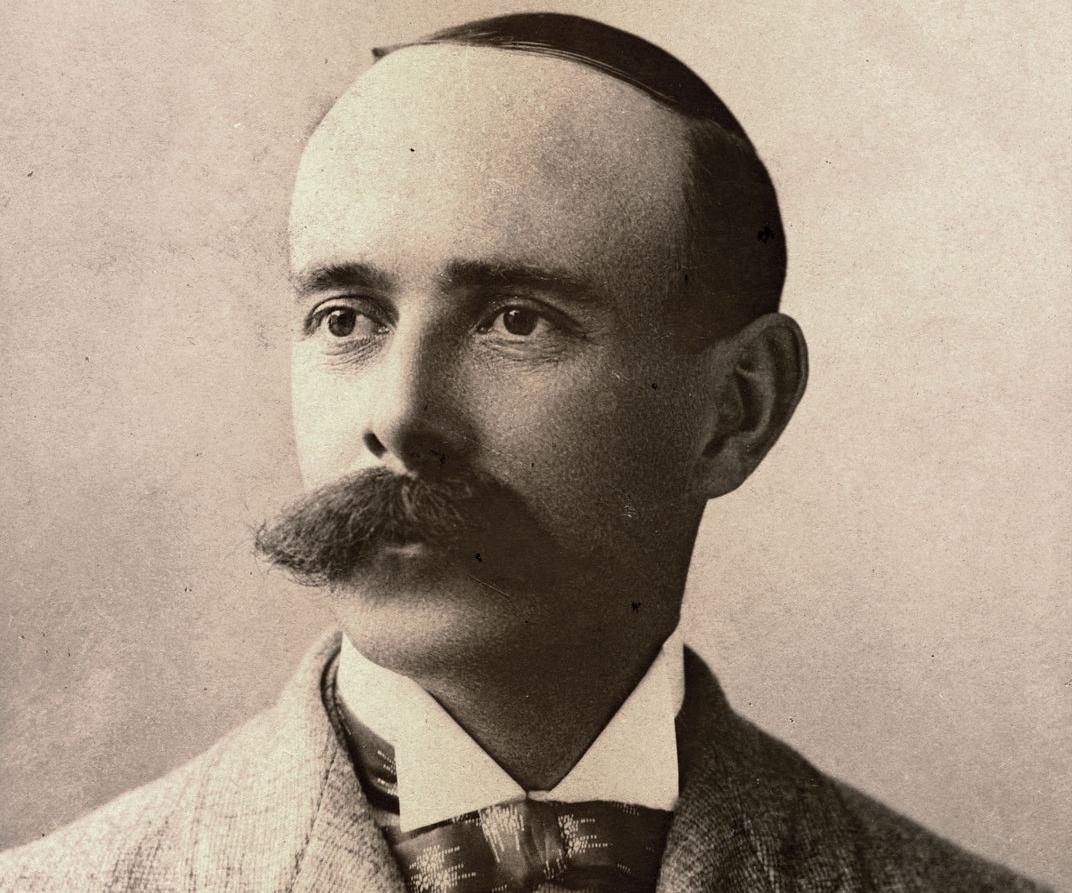

Frank Selee played some amateur ball in Melrose, Mass., before quitting his job at a watch factory in 1884 and forming a minor league team in nearby Waltham. Word spread quickly of Selee’s mind for the game and eye for talent as he developed that Massachusetts State league club.

Selee then joined and won a championship with another club in Lawrence, Mass. A two-year stint leading the New England league’s Haverhill team followed. He ventured to the Midwest in 1887, taking over the Oshkosh, Wis., team and capturing a Northwestern League title. Selee’s resume merited major league consideration and the National League’s Boston Beaneaters, moving on from manager Jim Hart, who reportedly allowed players too much freedom, had an opening after the 1889 season.

Enter the 30-year-old Selee, whom the Salt Lake Herald described, in stark contrast to Hart, as “a firm disciplinarian.” Hart, meanwhile, expressed his doubts about Selee’s future in Boston.

“Mr. Selee is, no doubt, a good manager, but no man can handle the present Boston team and suit all three directors, and get the best results out of the men,” Hart told The Boston Globe. “Selee is a king out in the Western League and is making as much money as he would get here, where he would most likely be a much smaller fish… Whoever comes and expects to please all hands will find no bed of roses.”

But early in his tenure, Selee appeared free to exercise his scouting prowess and improve the Beaneaters’ roster however possible.

“Manager Frank Selee mysteriously disappears every now and then from the sight of the Boston players,” wrote the Globe on May 2, 1890. “Rumor has it that Mr. Selee is hustling for a pitcher who can go in every other day and do his share of the work. The energetic little manager keeps his own counsel, and it is not yet known who he has his eyes on. He knows a ball player when he sees him, though, and it is not unlikely that he is negotiating with one of the stars.”

This pursuit of talent paid off quickly as Boston captured pennants in 1891, ‘92 and ‘93, along with another two in ‘97 and ‘98. Selee managed four seasons in Chicago after 12 in Boston, ultimately posting a .598 winning percentage with five pennants – and contrary to Hart’s warning, the transition to the big leagues proved well worth it.

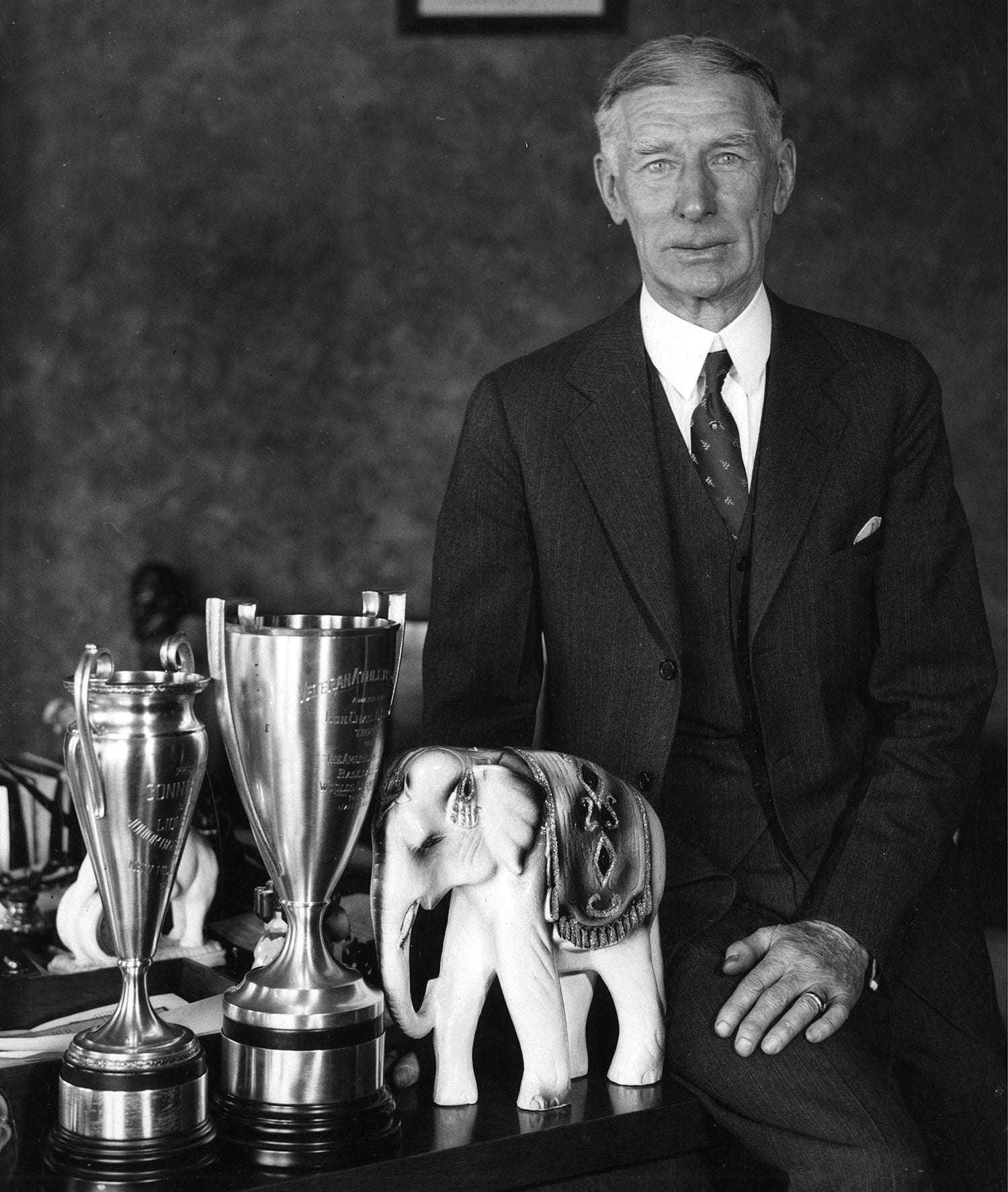

Joe McCarthy may be better known for his stretch of World Series-winning dominance with the Yankees beginning in 1931, but he earned his first managerial job, with the Cubs, in September of 1925.

Despite a roster featuring future Hall of Famers in Grover Cleveland Alexander, still a workhorse at age 38; Gabby Hartnett, the young, power-hitting catcher; and Rabbit Maranville, the glove-first shortstop who also managed 53 games that season, the 1925 Cubs won just 68 games and finished eighth in the National League.

Once a utility-type player, McCarthy had proven useful for various minor league teams, but at age 34 in 1921, still in the minors and yet to play in the big leagues, the player-manager dropped the first half of his title. And seven seasons managing the American Association’s Louisville Colonels finally put McCarthy on the radar of major league clubs, who recognized him as a strong leader and impressive developer of major league talent. Outfielder Earle Combs, for one, played for McCarthy’s Colonels before hitting .325 across 12 seasons with the Yankees.

So come 1925, McCarthy was no mystery to prospective big league employers, and the swooning Cubs, seven years removed from their most recent pennant, signed him to a reported $10,000 salary.

“The baseball writers say McCarthy has qualified with a vengeance as a developer of high calibered baseball talent,” wrote the Kenosha News in December of 1925, a few months after the hiring. “While in the managerial harness of the Louisville Colonels in the American Association, smiling Joe groomed many young stars and sent them up to the big show where they shine from prominent positions.”

That December, a testimonial ceremony took place in McCarthy’s hometown of Philadelphia to honor Chicago’s new skipper. Speakers included future Hall of Famer Connie Mack, midway through his half-century tenure with the Athletics, who silenced any doubts about McCarthy’s readiness for the big leagues.

“Do you know that it is easier to manage a big league club than a minor league team?,” Mack asked. “If you have a winner in the minors you can get along pretty well, but when you have a loser they will almost ride you out of town. On the other hand the fans stick with a big league manager and give him a better chance to develop a winning combination.

“I already know that he will be a success as manager of the Chicago team… I want to inform you all that there is no one who would like better than to see Joe McCarthy and the Chicago Cubs play the Athletics for the world’s championship next year.”

The Tall Tactician’s Athletics didn’t reach the World Series in 1926, nor did McCarthy’s Cubs. But Chicago improved to 82 wins, then 85, then 91. And in 1929, a 98-win season resulted in a National League pennant and a World Series appearance against none other than the Athletics. Mack’s club took that series in five games, but McCarthy had successfully returned the Cubs to relevance.

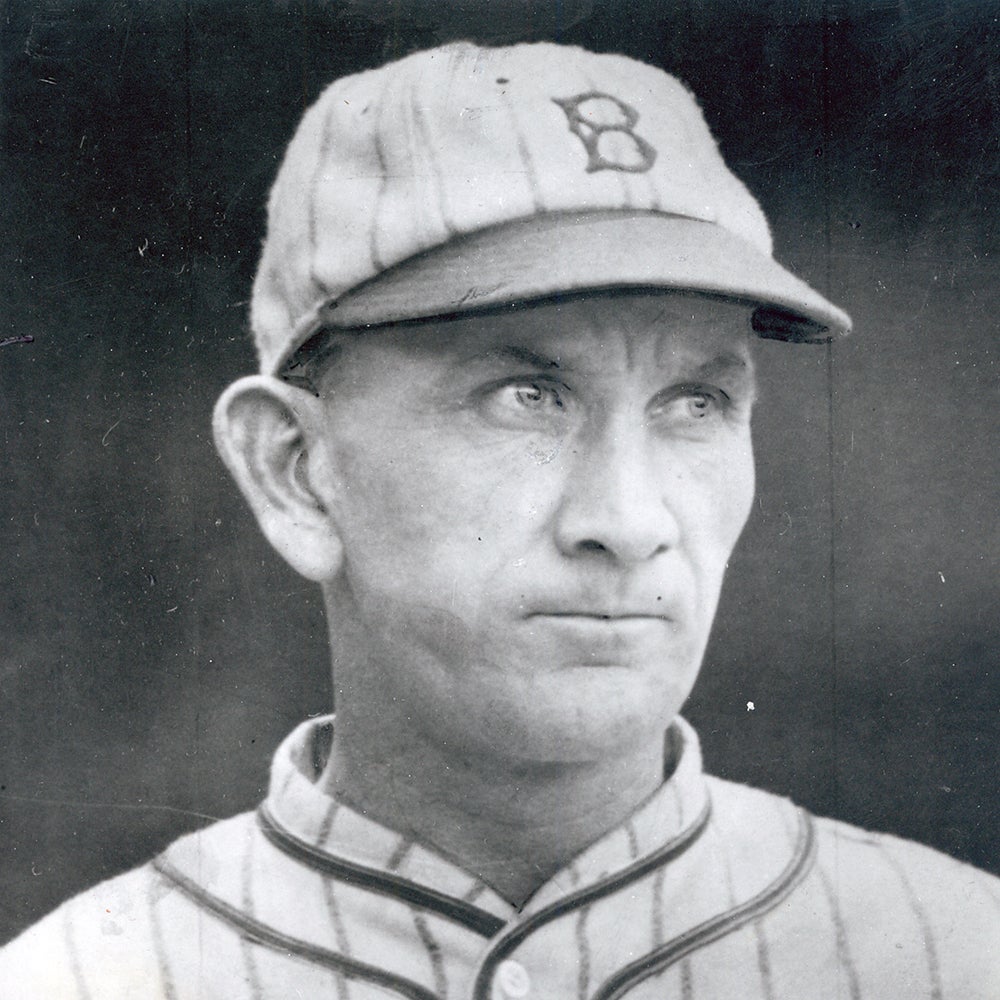

Earl Weaver joined the Orioles’ staff before the 1968 season, but not as manager. Skipper Hank Bauer had piloted Baltimore to a 1966 World Series title before an underwhelming 76-win performance the following year. Player personnel director Harry Dalton reportedly asked Bauer to resign that offseason, but Bauer refused.

Still, it was only a matter of time before Weaver took the reins in Baltimore. He’d risen through the Orioles’ system, managing his minor league clubs to a .532 winning percentage across several levels and 11 seasons.

As a player, the second baseman didn’t get to Triple-A until age 27, and he appeared in only four games at that level. For Weaver, the manager, however, the big leagues had finally felt within reach once he took over Triple-A Rochester in 1966.

“Then I saw other managers move up and felt there was no reason why I couldn’t do it,” Weaver told the Baltimore Sun.

When the 1968 All-Star break rolled around, Bauer had the Orioles in third place at 43-37. But Dalton expected more from a roster featuring talent like Dave McNally, Davey Johnson and future Hall of Famers Frank and Brooks Robinson, so he fired Bauer and named Weaver manager.

“The change was made because we felt we were more of a sputtering club than a hard-driving ball club,” Dalton told the Baltimore Sun, citing Weaver’s familiarity with the Orioles’ roster. “I think Earl Weaver is a winner. He’s been a winner wherever he’s been.

“He is very aggressive. He is a battler for his team, a battler for his organization and a battler for what he thinks is right on the ball club.”

“I still feel we are a pennant contender,” Weaver told the Sun. “I don’t think first place is unrealistic, even though we are 9½ games out. I think I inherited a good ball club. With one or two changes, I think it can be improved.”

Any immediate improvement wasn’t drastic, as Baltimore went 48-34 under Weaver to conclude the 1968 campaign and finished second in the American League. But aided by future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer’s return to the big leagues after a rough 1968, the Birds soared beginning in 1969, winning more than 100 games in three consecutive seasons. Pennants sandwiched around a 1970 World Series title as Weaver led one of the more dominant three-year stretches in baseball history.

So, how did Jim Leyland fare in Pittsburgh in 1986 under what was effectively a one-year tryout?

“I’m nervous, but I’m not scared,” he told the Post-Gazette upon being hired. “What difference does the length of the contract make? If these people aren’t satisfied with what I’ve done at the end of the year, I’m gone anyway.”

The Pirates went 64-98, but Leyland evidently showed enough promise to stick around. With help from young talent like Barry Bonds and Andy Van Slyke, Pittsburgh improved and, beginning in 1990, captured three straight division titles.

Eventually winning a World Series with the Marlins and reaching another two with Detroit, Leyland established himself as one of the greatest managers of all time, and in December of 2023 he was elected to the Hall of Fame.

“All those years in the minor leagues, I never really thought about coaching in big leagues,” Leyland told reporters after his election. “I was just a minor league manager and I never really thought that I was ever going to get that opportunity later on in my career. The Pittsburgh Pirates will always be a special place in my heart because they gave me my first opportunity to manage a major league team.”

Justin Alpert was a digital content specialist for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Hall of Fame election sinks in for Jim Leyland

Leyland "thrilled, excited, surprised" to earn Hall of Fame election

In 1968, Weaver began The Oriole Way in Baltimore

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hawk Harrelson