- Home

- Our Stories

- A’s celebrate 50 historic years in Oakland

A’s celebrate 50 historic years in Oakland

The phrase “fifty years ago” conjures up ancient recollections of something that happened so many years in the past that it seems like it occurred in another lifetime.

For those under the age of 50, that period of time was another lifetime, at least for those who believe in reincarnation.

But even for those older than 50, it’s a not-so-subtle reminder of how much time has passed. Could it really be that 1968 was 50 years ago? For some of us, that doesn’t seem possible.

In the case of the Oakland A’s, the number takes on special significance in 2018. It was 50 years ago – on April 17, 1968 – that the A’s played their first game in Oakland.

As a way of celebrating the milestone, the A’s presented a “50th Anniversary Team” during their Opening Day pregame ceremonies.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

On a more comical note, the A’s have also resuscitated Harvey the Rabbit, the mechanical animal that used to pop up out of the ground at the Oakland Coliseum and provide baseballs to the home plate umpire.

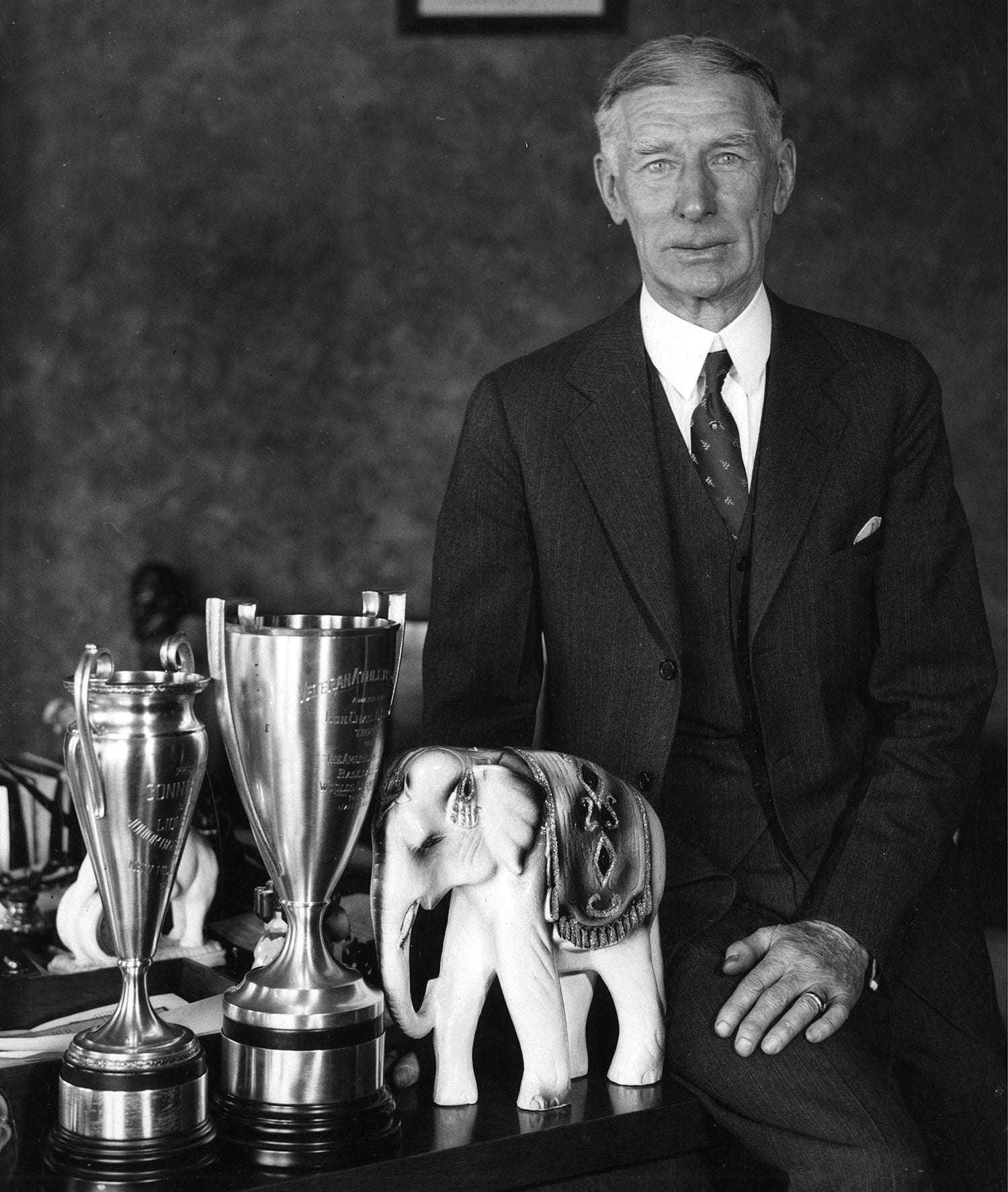

Prior to the 1968 season, the franchise had played in Kansas City, where winning eluded the A’s for all of their 13 seasons in the Midwest. Before that, dating back to the first half of the 20th century, there were prosperous years in Philadelphia, when Hall of Fame manager and owner Connie Mack tore down and built up several dynasties and took home five world championships before turning the franchise over to his sons, who eventually sold the team.

From 1955 to 1967, the A’s played in Kansas City, but never contended seriously for the American League pennant. Then came the move to the West Coast – and to the Bay Area. In transporting themselves to Oakland, the A’s became the fourth major league franchise to call the West Coast home, joining the California Angels, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Francisco Giants, the other residents of the Bay.

The arrival of Major League Baseball in Oakland in 1968 demands some context. It was a year of tumult in American culture, from the ongoing war in Vietnam to the horrific assassinations of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy to violent racial protests in numerous American cities. From a baseball perspective, it was a season that will forever be known as the “Year of the Pitcher,” a time when hitting conditions reached their nadir and pitchers prospered to no end. It was also the final season of the true pennant race; just one year later, the addition of four expansion clubs would mandate that each league separate its constituents into an Eastern and Western Division.

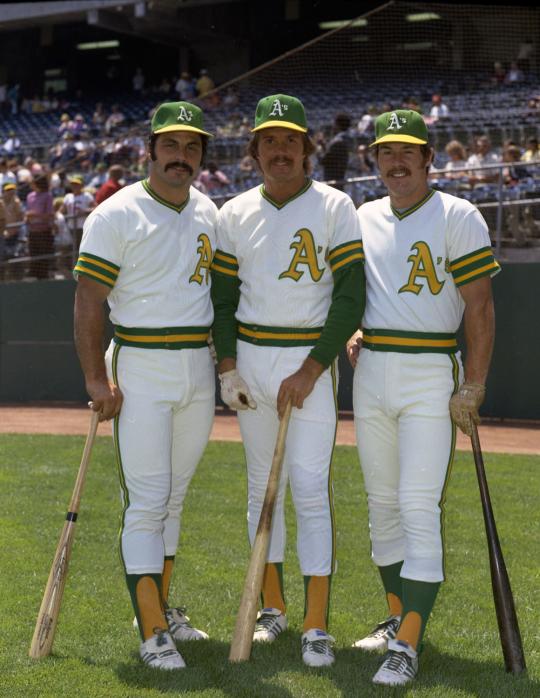

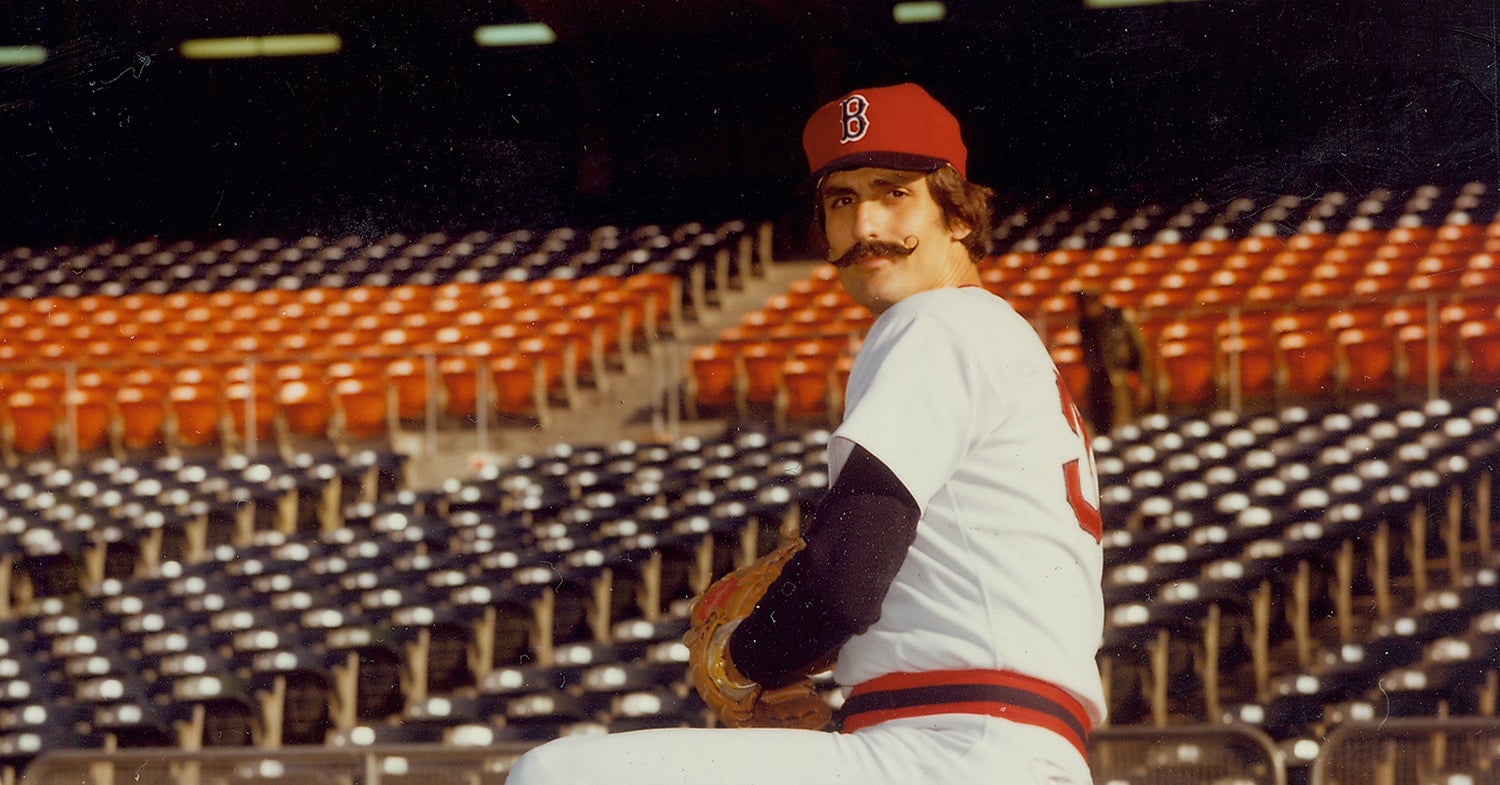

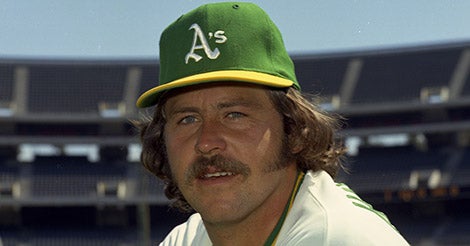

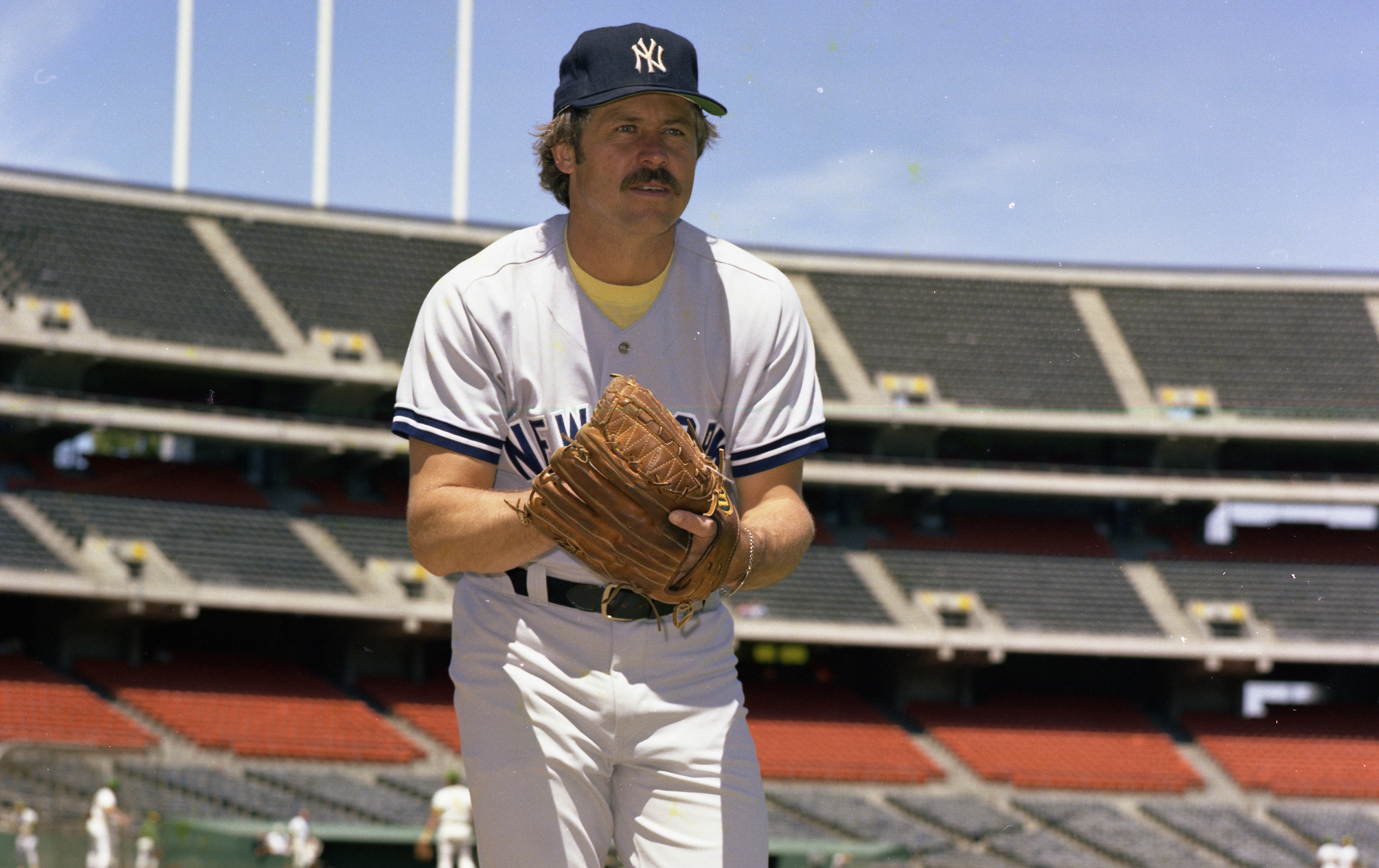

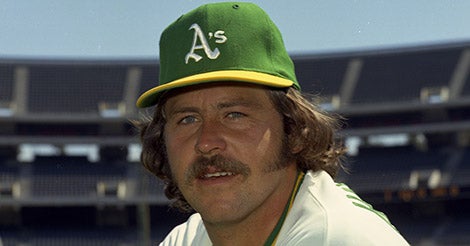

The 1972 Oakland A's were known throughout baseball as the "Mustache Gang” after the team started sporting facial hair once Reggie Jackson (center) showed up to Spring Training with a mustache. Pictured to the left of Jackson is Mike Epstein and on the right is Darold Knowles. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

In terms of the A’s franchise, the move out of Kansas City in 1968 had long appeared inevitable. Team owner Charlie Finley had seemingly been attempting to extract the A’s from Kansas City for seven years – virtually from the moment he bought the team from Arnold Johnson. Finley didn’t like the terms of his lease with the city of Kansas City, which resulted in repeated feuds with civic officials. At one point, the city asked for a rent of $500,000, which Finley felt was outrageous. Finley also felt that the city did little to support his efforts to improve attendance at Municipal Stadium, a longstanding problem in Kansas City.

In order to move the franchise, Finley needed at least seven out of 10 American League owners to give their approval. So Finley spent much of the 1967 season trying to curry favor with the other owners. Seventeen days after the regular season ended, Finley reached nirvana, as the New York Yankees switched their vote and became the seventh team to come over to the rebellious owner’s side. The 7-to-3 vote cleared the A’s to vacate the Midwest and move all of their belongings to Oakland, which had long been host to a Pacific Coast League franchise, the Oakland Oaks, but never to big league baseball.

The move to Oakland provided Finley with several advantages, including a new stadium (the Oakland Coliseum, which opened in 1966) and the opportunity for increased radio and TV revenue. In Kansas City, the A’s received only $50,000 a year in radio and TV money. In Oakland, that number would increase to $1 million.

As part of the original 1968 American League schedule, the A’s were supposed to make their debut as the Oakland A’s on April 9, 1968 in Baltimore, but tragic real world circumstances obliterated that plan. Dr. King had been assassinated on April 4; his funeral was scheduled for April 9. Not wanting to play on the day of the funeral, the A’s and the Orioles postponed the opener. Instead, they played the next day. Wearing uniforms that spelled out “OAKLAND” on the front of the jersey, the A’s took on the Orioles at Memorial Stadium. Future Hall of Famer Jim “Catfish” Hunter pitched brilliantly, allowing only one run over nine innings. But Baltimore’s Tom Phoebus was slightly better, emerging as the winning pitcher in a 1-0 shutout of the A’s.

After opening the season with a road trip to Baltimore, Washington, and New York, the A’s finally made their Oakland debut on Wednesday, April 17. Like their road uniforms, the A’s home uniforms once again featured “OAKLAND” on the front of the jersey. (Curiously, Finley would remove “OAKLAND” from both the home and road jerseys in 1969 and never again feature the city name on the team’s uniforms for the rest of his ownership tenure.) A crowd of 50,164 packed the Coliseum to see colorful right-hander Lew Krausse take on Orioles left-hander Dave McNally. Krausse struggled that night, allowing four runs in five and a third innings, while the Oakland offense mustered only two hits against McNally. One of the hits was a home run by Rick Monday, the only tally for the A’s in a 4-1 loss.

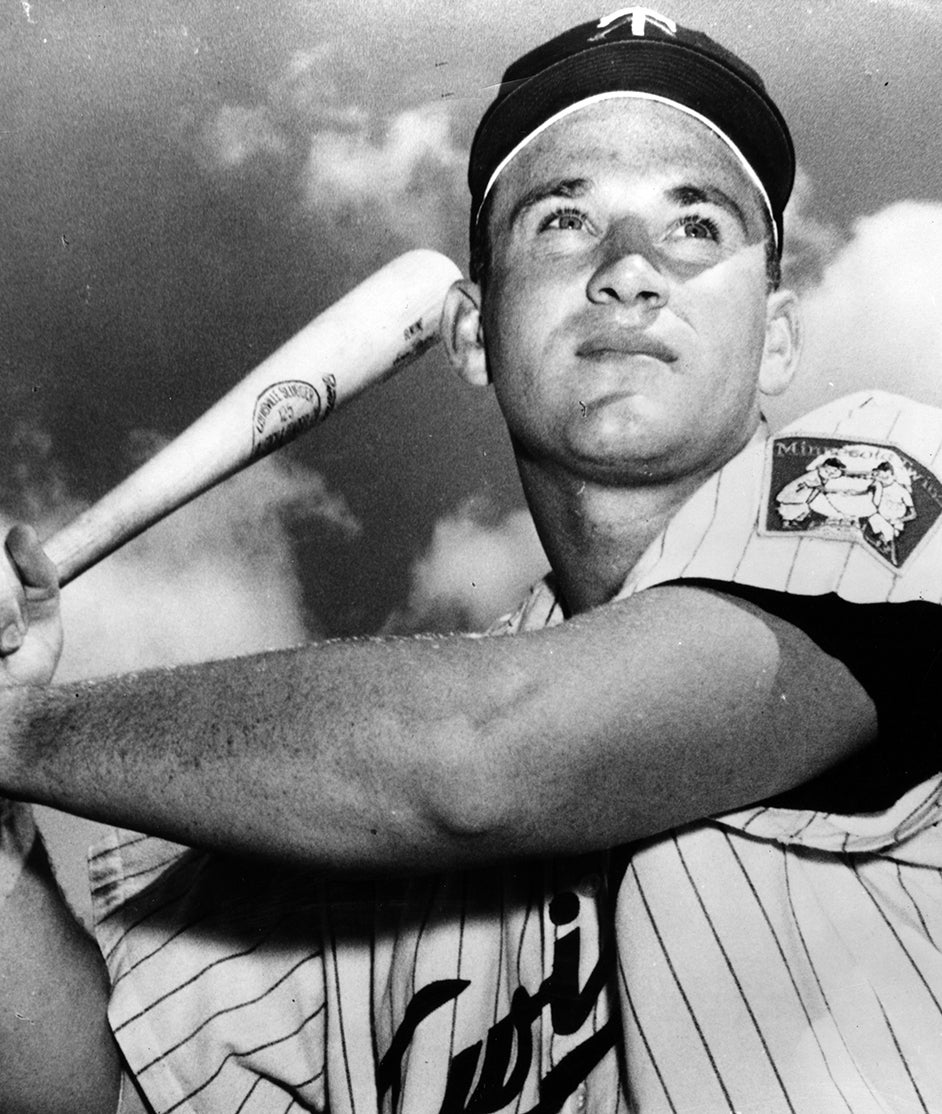

Although the A’s had lost both their road and home debuts in 1968, they would garner some positive national headlines less than a month later. On the night of May 8, a crowd of just under 6,300 fans gathered at the Oakland Coliseum. That night, Hunter faced the Minnesota Twins, a hard-hitting club that featured future Hall of Famers Rod Carew and Harmon Killebrew, two-time batting champion Tony Oliva, slugger Bob Allison and pesky leadoff man Cesar Tovar. In working against a vaunted Twins lineup, Hunter faced the minimum 27 batters to achieve a piece of immortality – a perfect game.

Hall of Famer Catfish Hunter wore this cap on May 8, 1968 when he threw a perfect game for the Oakland Athletics. PASTIME (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

With two outs in the ninth inning, Hunter struck out pinch-hitter Rich Reese on a three-and-two count, his 11th strikeout of the night. That was the completion to what A’s coach Joe DiMaggio, a celebrated hire by Finley, called “a masterpiece.” Hunter normally relied on precise control and finesse, rather than overpowering pitches, but against the Twins, he had every pitch working at an optimum level.

“Jimmy was always a very strong control pitcher,” said Jim Pagliaroni, who was Hunter’s catcher that night in Oakland. “But that night, not only did he have a hopping fastball moving around quite a bit, but he could throw his curveball (for strikes) at will. His slider was breaking exceptionally well. Plus, he also had a great change-up. It’s quite unusual when a pitcher keeps all of his pitches throughout the game – you usually have to work around one (ineffective) pitch. He was exceptional that night.”

Hunter was exceptional at the plate, as well. He had three hits and three RBI, essentially carrying the Oakland offense on a night when his pitching made most of the headlines. It’s no wonder that after the game, Finley announced that he was rewarding Hunter with a bonus of $5,000. That was no small sum for Finley, a man who normally guarded his money closer than a security guard watches Fort Knox.

Hunter’s perfect game remains well-preserved in Cooperstown, where the Hall of Fame and Museum house an array of important artifacts from that night. The collection includes Hunter’s cap, a game-used ball, and several scorecards that recorded the proceedings. Donated by Hunter, the ball is marked in pen with his signature and reads as Jim “Catfish” Hunter.

The cap, light green in color, carries special significance, not only because it belonged to Hunter, but also because of the change in the cap logo that season. During their years in Kansas City, the A’s featured a white, interlocking “KC” logo on the crown of that cap. That logo no longer fit the A’s now that they had moved to Oakland, so Finley changed the cap logo to a simple “A,” short for Athletics, or A’s. The A’s would use that style cap for only more season (1969) before switching the logo to the plural “A’s” in 1970.

Hunter’s perfect game represented the most memorable highlight of the A’s inaugural season in Oakland. But there were other good moments for a young, building team. The 1968 A’s finished with a winning record of 82-80, achieving in Oakland what they had never been able to muster in Kansas City. All five members of Oakland’s starting rotation won in double figures, while Reggie Jackson emerged as a premier slugger, hitting 29 home runs. In commemoration of that winning season, the Hall of Fame houses an official A’s pennant, the team’s official 1968 Yearbook, and a scorebook in its collection.

With a nucleus of Hunter, Jackson, Sal Bando, Bert Campaneris and Joe Rudi already in place, the 1968 A’s were on the precipice of greatness. Only three years later, they would win their first division title in Oakland. A year after that, they would become world champions, marking the start of the Finley dynasty.

The foundation to that dynasty was laid in 1968, a year in which pitching dominated the game, and in which assassination and war dominated the national news. On the grand scale, it was a supremely difficult year for the country, a year filled with far too much tragedy. On a smaller scale, for the fans in Oakland, it was the start of something good, with Major League Baseball finally arriving on the other side of the Bay.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

Jackson returns to Oakland to end career

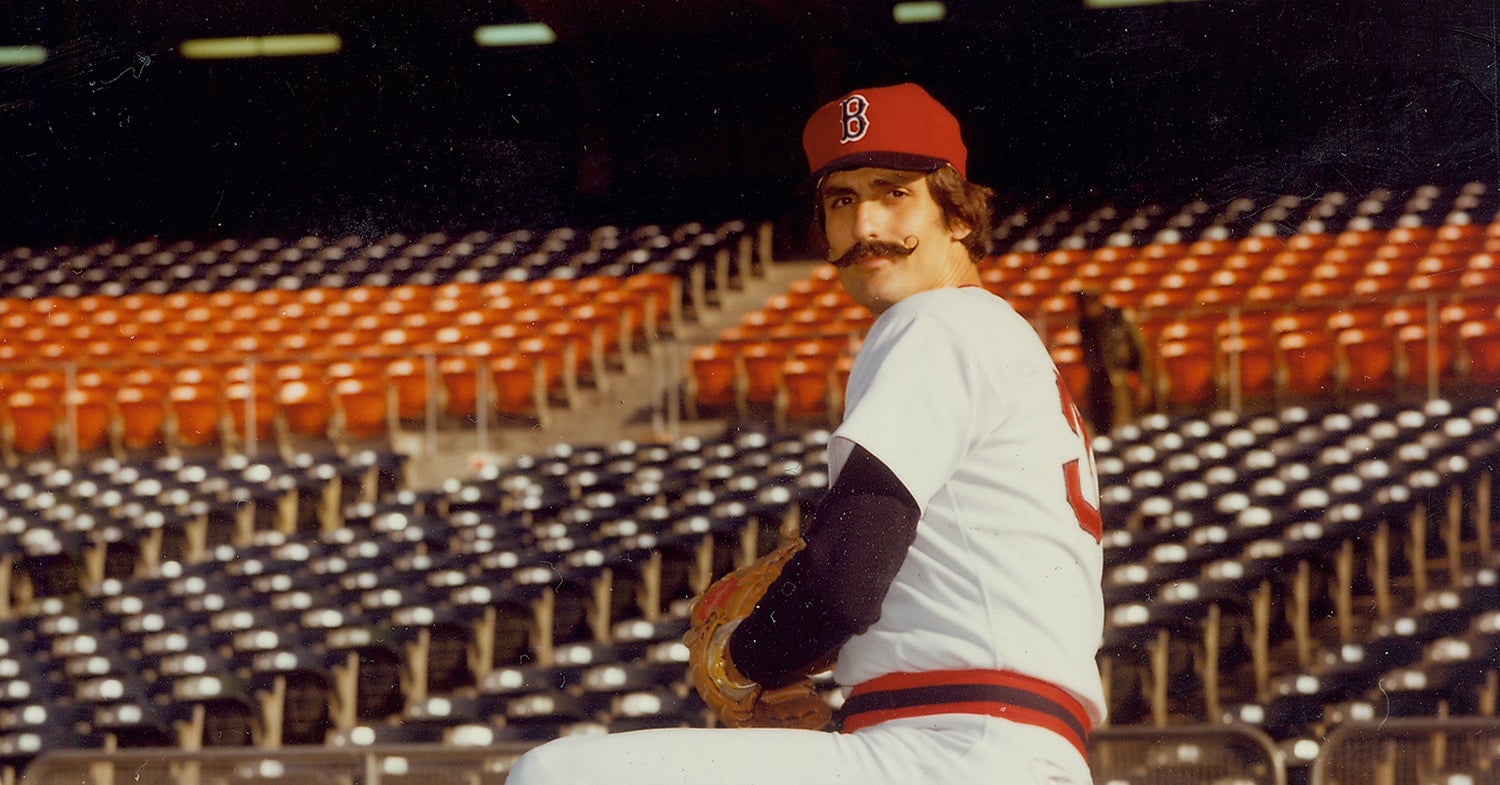

Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox

Catfish Hunter wins 1974 AL Cy Young Award

Hunter helped usher in free agency era

Jackson returns to Oakland to end career

Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox

Catfish Hunter wins 1974 AL Cy Young Award