- Home

- Our Stories

- 1918 flu pandemic did not spare baseball

1918 flu pandemic did not spare baseball

One hundred years ago, Silk O’Loughlin was considered one of the best and most renowned umpires in the major leagues. Then the famed arbiter, in the prime of his career, fell victim to an insidious, fast-acting infection that was killing thousands of people across the country in an astonishingly rapid rate.

With the horrors of World War I in their final year, a life-and-death battle on a more microscopic level was also taking place around the globe. The influenza pandemic of 1918 was a highly contagious strain that viciously attacked the respiratory system. By the time it had spread across the United States, the deadly event had killed an estimated 675,000 Americans.

And baseball was not immune.

The “Spanish flu,” as it was sometimes called at the time, lasted just 15 months but killed, according to best estimates today, between 50 million and 100 million worldwide. It infected an estimated 500 million people around the world, about a third of the planet’s total population.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“The disease is characterized by a sudden onset,” stated United States Surgeon General Rupert Blue in September 1918. “People are stricken on the streets or while at work. First there is a chill, then fever with temperatures from 101 to 103, headache, backache, reddening and running of the eyes, pains and aches all over the body, and general prostration. Persons so attacked should go to their homes at once, get into bed without delay and immediately call a physician.”

Influenza casualties during this deadly year included: Boston Globe sportswriter Eddie Martin, the secretary of the local chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America and one of the official scorers in the 1918 World Series; Philadelphia-based baseball writer Chandler Richter, son of The Sporting Life editor Francis S. Richter; and former Federal League umpire J.J. McNulty.

Among ballplayers, often recently active, the flu took: Cy Swain, a minor leaguer from 1904 to 1914 who slugged 39 home runs in 1913; Larry Chappell, a big league outfielder for the White Sox, Indians and Boston Braves between 1913 and 1917; catcher Leo McGraw, a minor leaguer between 1910 and 1916; catcher Harry Glenn, a minor leaguer from 1910 to 1918 who spent time with the 1915 Cardinals; minor league pitcher Dave Roth, who played between 1912 and 1916; and minor league pitcher Harry Acton, who played in 1917.

But when the 46-year-old O’Loughlin passed away on December 20, 1918, the reaction in the baseball community and among fans of the sports was shock and sorrow. Sports pages in newspapers across the country made note of the sad fact that the man who had ejected 164 men during his time in the majors was finally called out.

O’Loughlin died at his Boston apartment, where he was working in the offseason for the Department of Justice, after a short illness from influenza. His wife, Agnes, who had also been seriously ill with influenza at the time, survived him. His entire $25,000 estate was left to his widow.

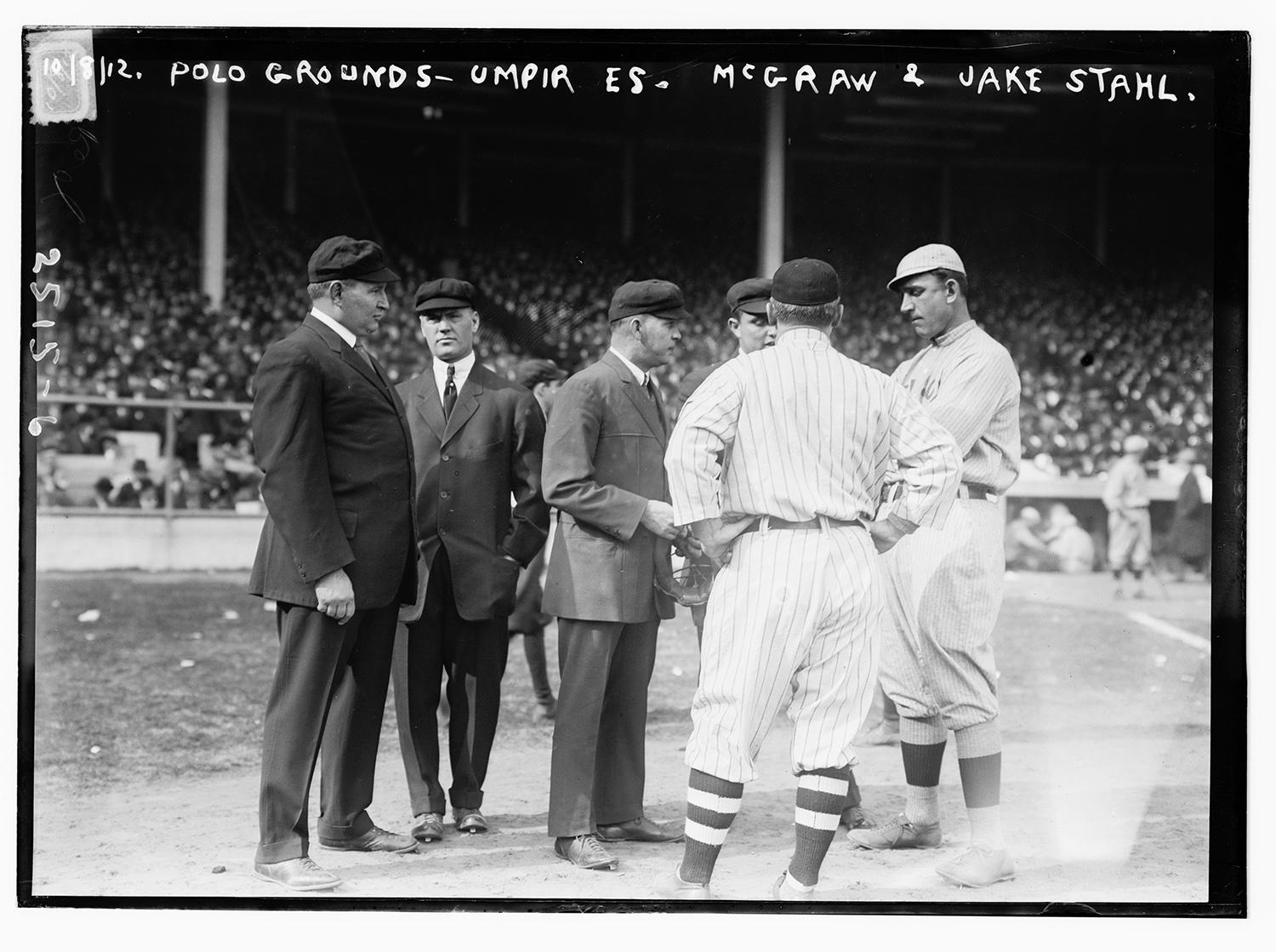

O’Loughlin umpired in the American League from 1902 to 1918 while working the World Series in 1906, 1909, 1912, 1915 and 1917.

The obituaries for O’Loughlin, who allegedly received his nickname as a child due to his silky blonde hair, often remarked that he was one of the most “picturesque” figures in the baseball world, “his ‘Ball tuh,’ his long, drown out ‘S-t-r-i-k-e!’ and snappy ‘Fouled-er!’ known the country over.”

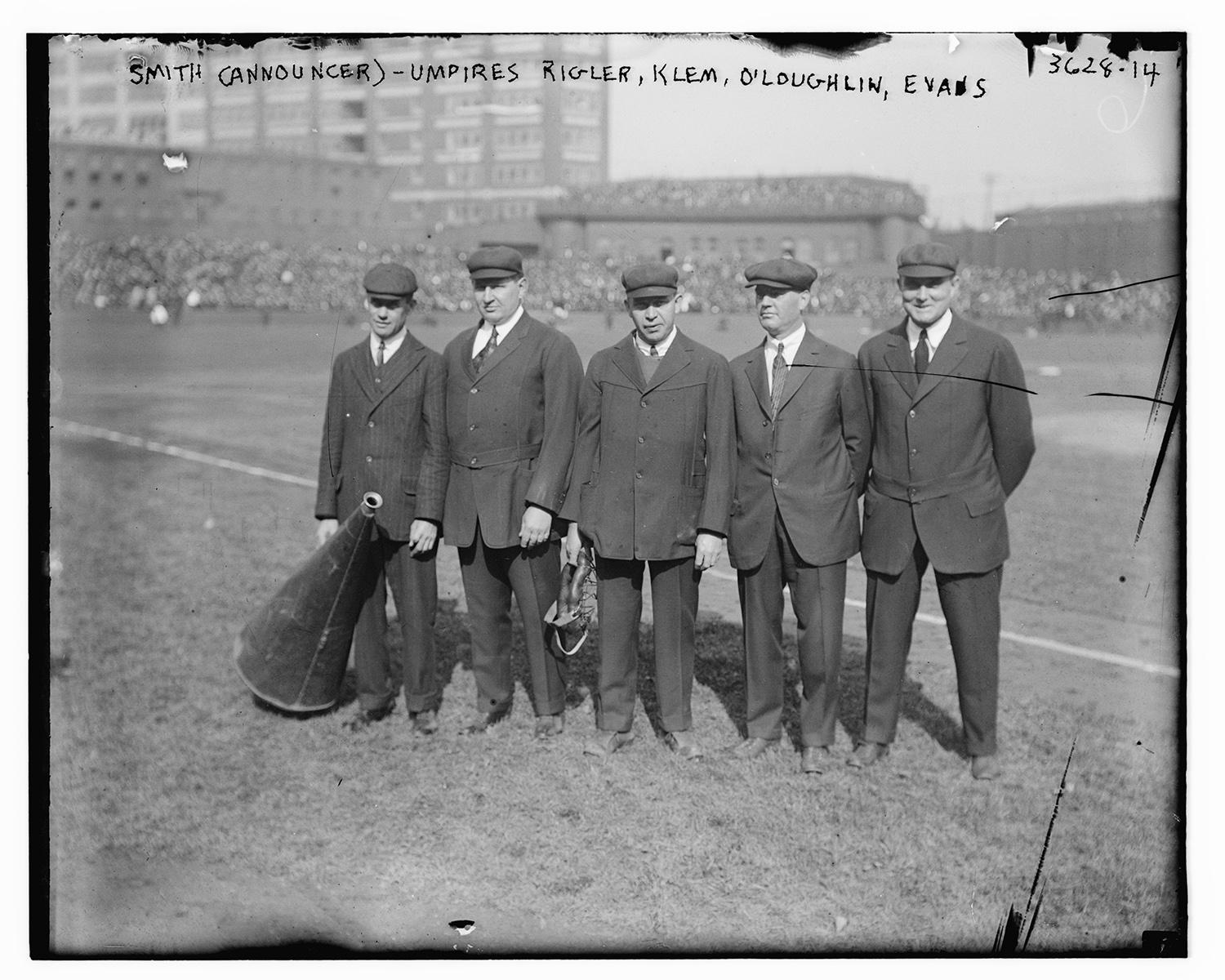

From left to right at the 1915 World Series: An unidentified Philadelphia Phillies announcer with umpires Cy Rigler, Bill Klem, Silk O’Loughlin and Billy Evans. O’Loughlin, a well-respected MLB umpire, fatally contracted influenza during the 1918 pandemic. (Photo courtesy of Library of Congress)

“In the death of Silk O’Loughlin the country has lost a worthwhile citizen, baseball has lost a remarkable character, and I have lost one of my dearest friends,” said umpire Billy Evans, a 1973 Baseball Hall of Fame electee who worked games with O’Loughlin. “If there ever was an umpire who gave the plays as he saw them, O’Loughlin was that individual. He had a heart of oak, a keen intellect, and the courage to do what he believed was right, regardless of the opinion of others. Through 17 years of service as a member of the American League staff of umpires he gave the best he had. He never shirked. He never grumbled over an assignment, always accepting them as they came as part of the game.”

The Rochester, N.Y., native got involved with professional baseball with the help of relative Stump Weidman, a big league pitcher from 1880 to 1888. Soon he was umpiring in the Atlantic League, then the Eastern League, before making his Junior Circuit debut in 1902 at the age of 29.

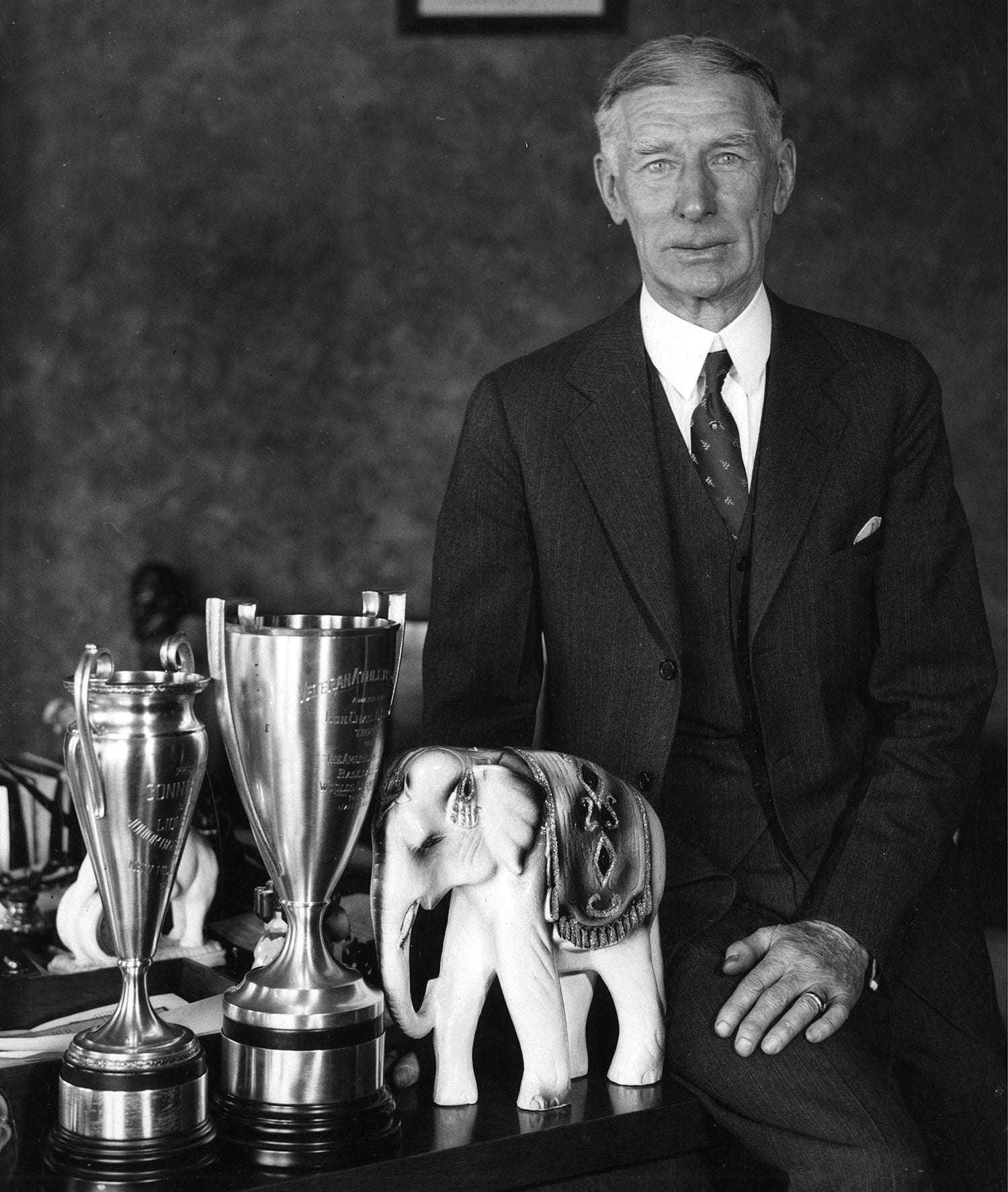

A pair of veteran baseman men, Connie Mack and Clark Griffith, had kind words for their fallen comrade.

“O’Loughlin was original and always a hard worker,” said Mack, Philadelphia Athletics owner and manager, “and his death will be mourned by all baseball fans.”

“His death is a real loss to baseball,” said Griffith, manager and part-owner of the Washington Senators. “No squarer or more honest official ever made decisions in a ballpark. He had the courage of his convictions always, and was admired and respected by players and fans alike.”

Called “the little indicator holder with the megaphone voice,” O’Loughlin, who, when a played disagreed over a call would tell him that he had made over a million decisions in his day and had never missed one, shared his umpiring philosophy in the September 1911 issue of Baseball Magazine:“Be boss of the diamond. An umpire, like a player, must think in advance. He must know each man’s peculiarities, his strength and weakness,” O’Loughlin wrote. “He must so plan that he is in the most advantageous position to render instant decision upon every play and at the same time must not interfere with the play.

“Running his own game does not mean surliness. It means the umpire is sent onto the field to represent the league, to decide plays and interpret the rules. He may not tolerate interference; he may not permit a player to ‘show him up.’ He must retain his dignity and not permit an argument.

“He should not make his decision too quick or he may have to change it. It isn’t a good thing to have to change decisions, and earn a reputation for being premature.

“Ballplayers are human, and when they realize an umpire is stern, but just, they are less apt to kick over the traces even in the heat of a hotly contested game than if they have reason to believe they can gain anything by attempting to bullyrag. Of course umpires make mistakes, not being infallible, but on the whole their decisions are correct, as the players admit when off the field, although sometimes they find it hard to do so when the battle is raging.”

The veteran arbiter, known for his the sweeping gestures and pronounced exclamations, had a sharp tongue and a ready wit. It was said that his favorite expression was that there were no close decisions in baseball.

“I have never made a wrong decision. At least, if I did I never admitted it, which amounts to the same thing,” O’Loughlin once said. “If I ever do make a mistake it would be idiotic for me to tell it. Of course there are lots of times when ballplayers and fans don’t agree with me, but I’ve found that what I say always goes so it must be right.

“My skin is think enough to shed the criticisms heaped upon me. I don’t stop speaking to newspapermen when they roast me, and I don’t find fault with the players who grumble in the heat of battle.”

O’Loughlin’s funeral in Rochester on December 23, 1918, was said to have been one of the most largely attended in the history of the city.

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

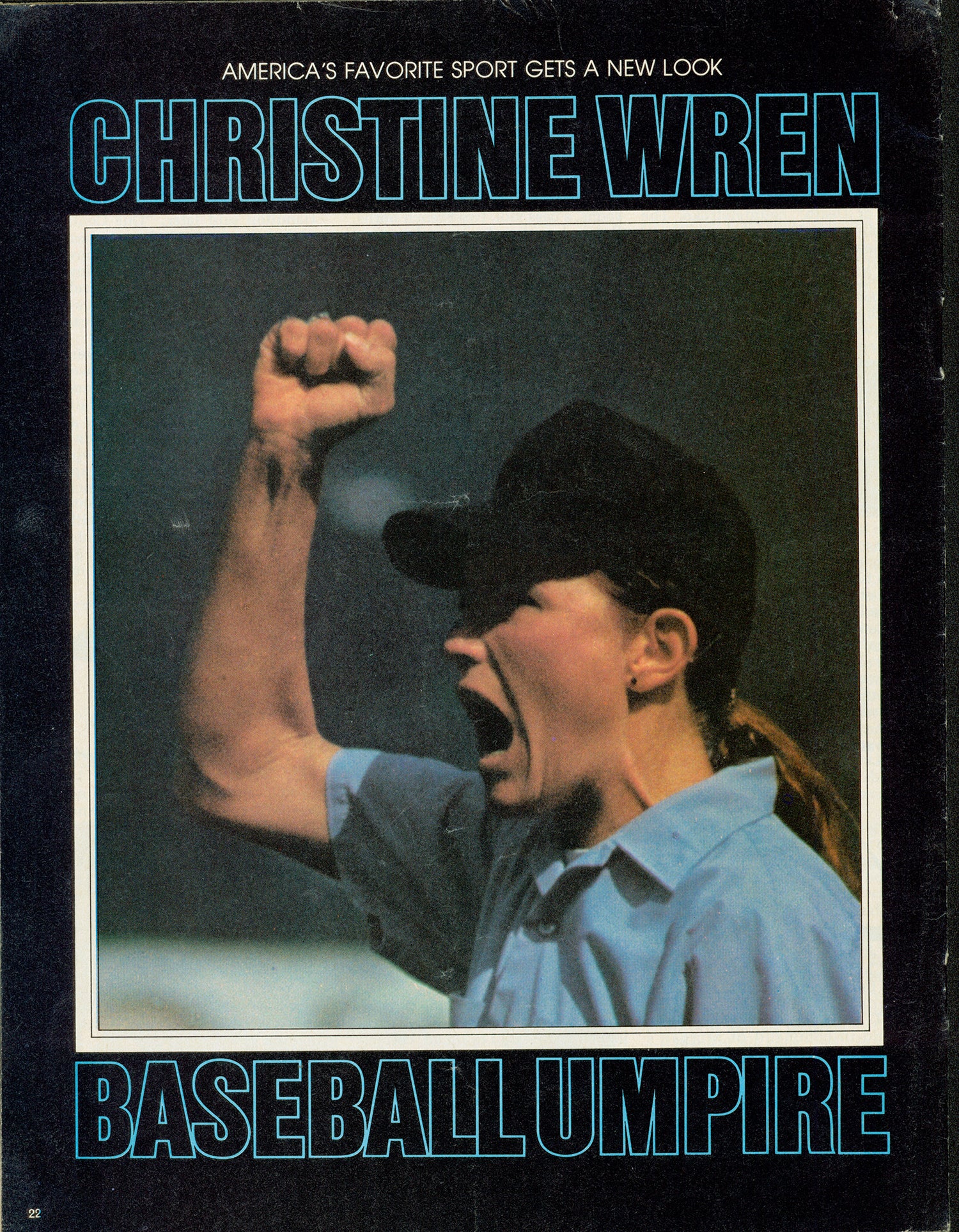

Umpire Unmasked: Christine Wren Opens Up About Her Life As a Baseball Pioneer

Umpires Break Through Glass Ceiling

Umpire Unmasked: Christine Wren Opens Up About Her Life As a Baseball Pioneer