I’ve never been afraid of anything, but I was scared on that trip to Russia.

- Home

- Our Stories

- Field of Frozen Dreams

Field of Frozen Dreams

In the early spring of 1943, Navy signalman Clifford Stewart was stranded.

A young man who hailed from the Midwest, Stewart stood at the edge of the Arctic Circle. He and his fellow shipmates were in a foreign land. The natives around him spoke a different language. It was wartime, and the shores of America were more than 4,000 miles away. A return home seemed unlikely, at least not anytime soon.

Amidst all this isolation and uncertainty, Stewart and his mates turned to one activity to remind them of home: Baseball.

More than seven decades after he and the crews of four ships that were part of the famous “Forgotten Convoy” played baseball in eastern Russia, Stewart is donating a homemade bat and ball from those lost games to the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. These items join a small collection of artifacts from folks – including detained newsmen and photographers in Bad Nauheim, Germany, and imprisoned Japanese-Americans in the American Southwest – who manufactured their own equipment to play baseball among some of the most dire wartime circumstances.

“We see examples throughout World War II of people turning to baseball,” said Erik Strohl, vice president of exhibitions and collections at the Hall, “for that reminder and for that solace.”

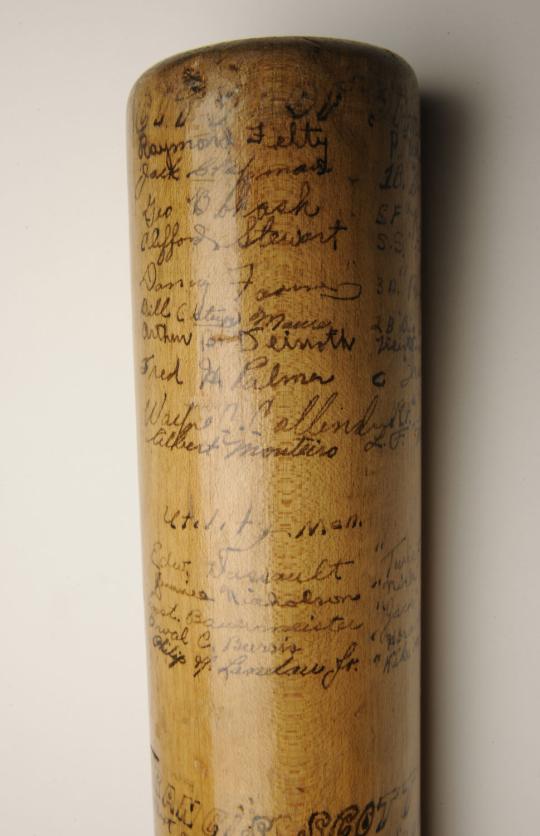

Strohl traveled to Stewart’s home in Healdsburg, Calif., to collect the donation, and Stewart gave him an “ingredient list” to accompany his handmade relics. The bat, featuring the inscribed seamen’s names who played in the makeshift “White Sea League,” was crafted on a lathe from a tree branch. The ball began with a rubber plug from one of the ship’s engine rooms, which was then wound with string and covered with leather from Navy boots. The players used the hot shellmen’s gloves, worn to handle scalding artillery casings in battle, as mitts.

Stewart, a retired Navy captain who turned 99 on Tuesday, said he had shown the bat and ball to friends and relatives throughout the years, but had not considered donating them to the Hall until recently.

“I don’t know why I kept (the bat), I had no reason to keep it,” he reflected. “But when my neighbor (Brian Galloway) saw it he said, ‘That should be in the Hall of Fame!’… He was the spark I needed.”

A Dangerous Mission

Stewart’s life of public service began as a necessity when the Great Depression crippled the United States. He had been working as a paper boy, and doing better than most, when he finally received his share of financial misfortune.

“I was the richest kid in town,” Stewart recalled. “But when a bank closed back then, a bank really closed, and I lost every cent I had. That’s why I joined the CCC right after high school.”

Stewart kept a small portion of his earnings and sent the rest back to his family in Missouri during his time with the Civilian Conservation Corps. He also began playing baseball more frequently, a hobby he would continue when he transferred to the U.S. Forest Service as a fire watchman.

He enlisted in the Navy in 1942 and received his boot camp training in San Diego. After a brief convoy operation in Egypt, Stewart got his next assignment: A supply run carrying vital food and war materials to Murmansk, Russia.

Stewart set sail aboard the S.S. City of Omaha out of a port in Scotland in Jan. 1943, alongside five American and 18 Allied merchant vessels. The convoy soon encountered hurricane-force winds and rain that was anything but welcoming.

“The ship would go down to the bottom of the trough and you would see nothing but water,” Stewart said. “Then you’d get back up to the top and see everything from the crest. It was colder than hell and I remember the ship was a white blur; it was covered with ice.”

Stewart’s duty as a signalman was to relay messages with flag semaphore. He recalled one time when he nearly slid off the icy deck and into the freezing waters, an experience he will likely never forget.

“I’ve never been afraid of anything,” he said, “but I was scared on that trip to Russia.”

When the weather finally cleared near the northern coast of Norway, the convoy confronted perhaps an even more dangerous opponent: German U-boats. Stewart’s vessel, a hog islander cargo ship built in 1920, was a prime target.

“The ship I was on still had plenty of weapons on it, so we knew (the Germans) were going to pick on us,” he recalled. “So they shifted us around in the convoy every once in a while.”

Retired Navy Captain Clifford Stewart holds a bat and ball used by members of the “Forgotten Convoy” during the summer of 1943 in Severodvinsk (formerly Molotovsk), Russia. Stewart donated the baseball artifacts, which were handmade by the convoy sailors, to the Hall of Fame in June. (Erik Strohl / National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Stuck in the Arctic

The convoy arrived battered and diminished in Murmansk at the beginning of March, after six merchant ships had been forced to turn around during the storm. After dropping off the supplies, the City of Omaha and three other U.S. ships were commanded to continue on to Molotovsk, now known as Severodvinsk, and await the arrival of an escort back to the United States.

Stewart and his fellow seamen arrived at the mouth of the White Sea to find it frozen solid. A second icebreaker was called in to help clear the path to Molotovsk. Once they landed, however, the sailors learned that all convoys had been halted.

And so, stuck in the Arctic and with nearly 24 hours of daylight at their disposal, they turned to baseball to pass the time. The White Sea League was formed, comprised of four teams – one for each ship. The local Russian citizens leveled off a field for the sailors to play on, even if they didn’t fully understand the strange American sport.

“We drew a pretty good crowd,” says Stewart. “They wanted to see what those crazy Americans were doing.”

The City of Omaha ship prevailed in the first half of the season but fell in the championship series to the S.S. Francis Scott Key, as Stewart’s bat denotes. Though he cannot recall specifically how many games the teams played, they surely helped take the sailors’ minds off their growing estrangement from home. All told, the members of the “Forgotten Convoy” spent nine months in Molotovsk, and nearly a year in total away from the United States.

Remarkably, Stewart’s time by the White Sea would become just a small blip on a remarkable and prolific military resume. He enrolled in officer training school when he returned home, and eventually rose to captain, serving seven different commands in Korea, Vietnam, on the home front and in the Pentagon.

Players in the White Sea League, a makeshift baseball league comprised of sailors from the “Forgotten Convoy” who were stranded during the summer of 1943, in Severodvinsk (formerly Molotovsk), Russia, inscribed their names on this handmade bat. The bat is now part of the Museum collection. (Milo Stewart, Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

In 1944, the members of the “Forgotten Convoy” were invited to a reunion at the White House by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a party Stewart was unable to attend. His subsequent list of medals and ribbons read like a Hall of Fame plaque for military service.

After retiring from the U.S. Navy in 1974, Stewart stayed as active as ever, serving as president of the local farm bureau near his home in California and helping to build a dam at Lake Sonoma. When asked how recently he retired, the 99-year old had a simple answer.

“I haven’t yet.”

A sense of the familiar

Strohl says he is thrilled to add Captain Stewart’s bat and ball to the Museum’s collection, because the artifacts will help the Hall to continue to tell the story of baseball’s prominence in the American experience.

“Baseball is a microcosm for what is happening in American culture,” Strohl said. “Almost anything in American history as a whole, whether it’s segregation and integration, or the evolution of technology or even in pop culture, you can see it also happening as a microcosm in baseball history.”

Indeed, throughout the last century and a half it seems that many Americans, when faced with daunting challenges like a lonely summer in Russia, have turned to the National Pastime for comfort.

“Baseball was a symbol for these people,” Strohl said. “I can only imagine what it would have been like for these guys to have been stuck, and what do they turn to? They turn to baseball to give them a little peace of mind and a reminder of home.

“It was a little bit of something familiar when you’re surrounded by so much that is unfamiliar.”

Matt Kelly is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum