- Home

- Our Stories

- The deal that changed the game

The deal that changed the game

In the early months of 1919, everything appeared to be going smoothly for the Red Sox.

Just below the surface, however, financial woes were threatening the future of the Boston club. Despite a pennant-winning season in 1918, dwindling wartime attendance caused the club’s gate receipts to drop 35 percent. Meanwhile, club owner Harry Frazee was hemorrhaging money due to struggles with his theatrical productions in New York.

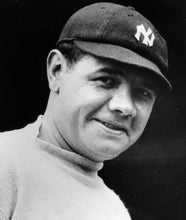

Amid all of this, the team’s most popular player began to feel that he was worth more than what he was being paid. In January 1919, Babe Ruth demanded a new contract. Specifically, he requested his yearly salary be raised from $7,000 to $15,000 – a figure that only the great Ty Cobb was making at the time. He also wanted to play left field exclusively, telling the press, “I’ll win more games playing every day in the outfield than I will pitching every fourth day.”

Frazee scoffed at Ruth’s demands, and Ruth held out and became front-page fodder for Hub newspapers. But when the team’s ship set sail for Spring Training in Florida – and a lucrative exhibition series scheduled with John McGraw’s Giants – without its star on board, both sides sensed it was time to come to the table. Frazee and Ruth settled for a $10,000 yearly salary just weeks before Opening Day, but when the slugger set a new home run record with 29 blasts in 1919, it was clear that new three-year contract would not stick. That winter, Yankees owners Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast Huston offered the cash-poor Frazee a deal he felt he couldn’t refuse, setting into motion perhaps the most famous sale in sports history.

This promissory note in the Hall of Fame Library Archive documents an agreement that dramatically altered the fortunes of two of baseball’s most famous franchises. The terms for Ruth’s sale to the Yankees, for a then-astronomical $100,000, were as follows: Ruppert and Huston paid Frazee $25,000 in cash up front, followed by three promissory notes scheduled for Nov. 1 on each of the following three years. A promissory note is a legal document in which one side (in this case Ruppert and Huston) agrees to pay the other side (Frazee) on a fixed date in the future. The note in the Hall of Fame archive, featuring the signatures of all three team owners, is for the first scheduled payment on Nov. 1, 1920.

According to Ruth biographer Robert W. Creamer, each promissory note was valued at six percent interest, meaning the Yankees were actually paying the Red Sox closer to $110,000. Ruppert also agreed to loan Frazee an additional $300,000, and in exchange the Yankee owner held a mortgage on Boston’s Fenway Park (Creamer describes this as being a “crux” of the deal). A closer look also reveals the date on this promissory note as Dec. 26, 1919 – that’s the date when the owners agreed to the deal. They agreed to wait until Ruth agreed to the terms to announce his sale to the press, and that’s where things became more complicated.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Ruth was not in Boston at the time the deal was struck – he was in California. As Ruppert and Huston discussed terms with Frazee, they dispatched manager Miller Huggins to Los Angeles to talk to Ruth. After some initial difficulties, Huggins eventually did find the slugger on a golf course, according to Creamer’s book Babe: The Legend Comes to Life. Ruth initially demanded an unprecedented $20,000 salary and a cut of Ruppert’s cash payment to Frazee. Huggins was able to eventually talk Ruth into $10,000, along with $21,000 more in bonuses to be paid out regularly during the 1920 and 1921 seasons.

When the sale of Babe Ruth was finally released to the press on Jan. 5, 1920 – 11 days after it was first struck – the reaction was a mix of despair in Boston and excitement in New York. But it also elicited early hints of the public’s fascination toward skyrocketing player salaries – an issue that would characterize labor negotiations in baseball many decades later. In a Jan. 7 editorial, The New York Times wrote:

“Neither club can be blamed for its part in this affair; but it marks another long step toward the concentration of baseball playing talent in the largest cities, which can afford to pay the highest prices for it. That is a bad thing for the game; and it is still worse to give a valuable player stranded on a weak club the idea that if he holds out for an imposing salary he can get somebody in New York or Chicago to pay for his services.”

Frazee did his best to downplay the effects of the sale, labeling Ruth as “selfish” to the press and saying the Yankees were “taking a gamble.” But while the Yankees ended up paying nearly half a million dollars for the slugger (taking into account the sum of the original sale, the money loan to Frazee, Ruth’s yearly salary and his subsequent bonuses), the imminent World Series championships and prestige to come makes it fair to say in hindsight that the “gamble” paid off.

Matt Kelly was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

related content

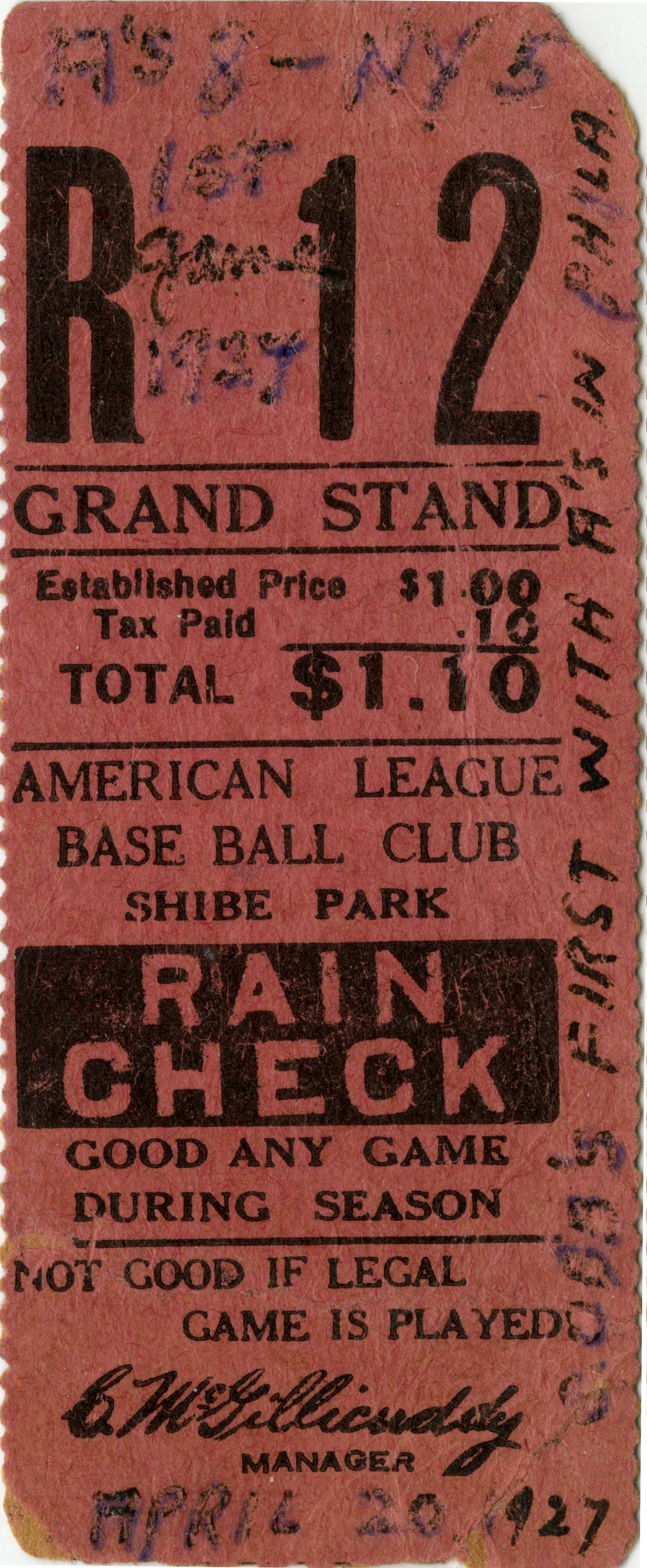

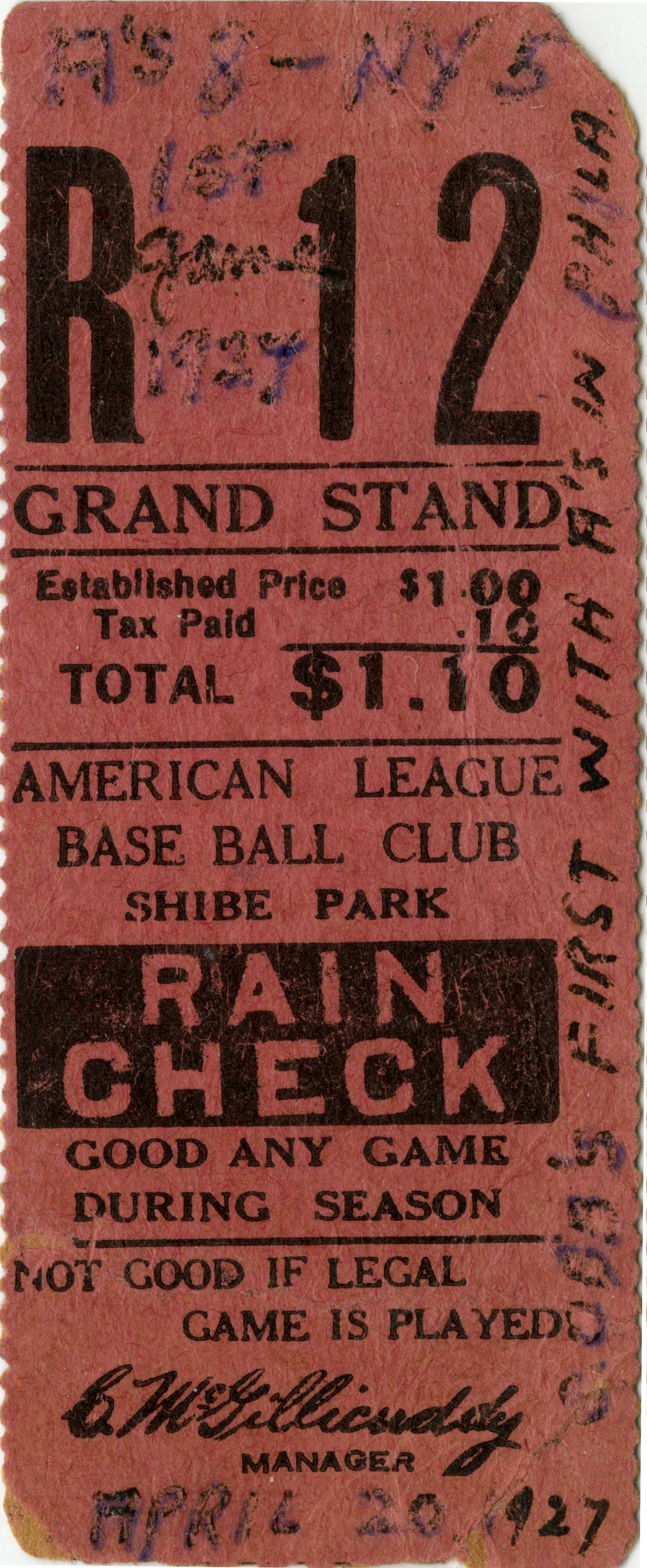

Just the Ticket for Cobb