- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball cartoons worth much more than a thousand words

Baseball cartoons worth much more than a thousand words

From its earliest 19th-century days, baseball has maintained great cultural significance in this country. The sport has shared in America’s growing pains, mirroring the country’s resistance to, and acceptance of, change. It has supported war efforts, led the way in the fight against segregation, and followed the same capitalistic business practices upon which this country was built.

And all the while, the history has been told through the pens and pencils of American cartoonists.

What makes cartoons unique is their ability to act as “snapshots” of a given place and time, while simultaneously providing more commentary than a photograph. They illustrate how people think about particular issues, with the added benefit of not holding back criticism. The American public has found the use of cartoon art to be an accessible form of communication, one which can entertain, and at the same time, expose truths about our ideals and habits. Since baseball has been around for much of our country’s history, baseball cartoons have had a peculiar advantage in capturing the public’s attention by providing a visual context with which readers could identify.

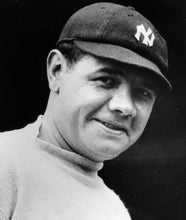

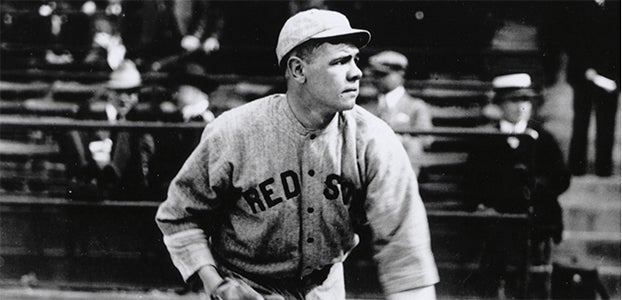

A cultural icon, Babe Ruth is represented throughout the Museum’s Digital Collection. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Many baseball cartoons had a singular function: To inform readers about the performances of players and clubs. Other cartoons were meant to entice thought on certain topics, from politics to segregation to salary levels. Still others reflected the intertwining histories of baseball and the American people, whether it was through military conflict or technological change. Baseball cartoons, appearing first in the 1860s as lithograph prints (both individually and in humor magazines) before progressing to the daily newspapers, eventually reached their peak from the 1940s through the 1960s.

By the 1860s, Currier and Ives, among other lithograph companies, began manufacturing mass-produced prints that used baseball as a major theme. This was only 15 years after the New York Knickerbockers first codified and published the rules upon which today’s game is based. Artists recognized that baseball was quickly becoming an integral part of our recreation and culture. They also realized that as an increasingly popular product, it could sell.

Cartoons appearing as lithograph prints signaled the viable use of baseball as a successful subject for the cartoon medium. The popularity of cartoons increased dramatically with the birth of American humor magazines. Beginning in the 1870s, publications like Puck, Judge and Life contained a proliferation of cartoons. Printed on smooth stock, it was easier for cartoons to contain delicacy in craftsmanship. Advances in technology also allowed lithographs to be colorized mechanically, adding greatly to their appeal. The birth of these magazines coincided with the first decades of the professionalization of baseball, beginning with the formation of the National Association and National League in the 1870s. Community-wide participation in baseball increased as “boosterism” became more rabid and fans rallied around the successes of the local pro club. As baseball was transformed from a social club activity to a for-profit spectator sport, the public’s perception of the game changed. It is no surprise, then, that cartoons about baseball appeared in increasing number and variety in these magazines.

By the 1890s, newspapers and sporting publications around the country began to produce cartoons on a regular basis. The growth of large, concentrated city populations, along with improved printing technologies like photoengraving and the Linotype, fueled the production and consumption of both newspaper journalism and cartoon art.

Americans were now being drawn to the sensational “yellow journalism” of the period, which thrived on headlines and cartoons to convey news quickly. This “at-all-costs” method of sensationalistic journalism spurred the growth of the entire industry and promoted the use of cartoons as a vital element for any successful newspaper. By the early decades on the 1900s, almost 2,000 daily newspapers were published across the United States taking advantage of this graphic revolution. Cartoons were being embraced as a legitimate way to draw readership.

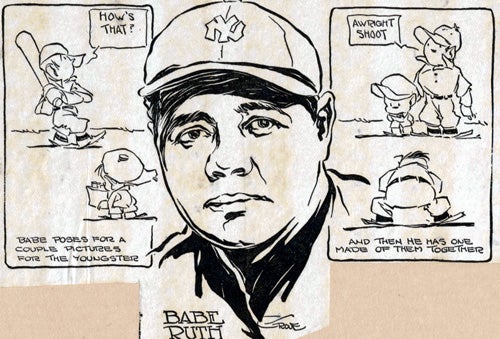

Like their sportswriting brethren, cartoonists found a natural use for baseball in their work. They realized the public’s affinity for the game was a full-blown cultural obsession. As professional baseball stabilized into two major leagues with an annual World Series championship, coverage of both the major and minor leagues proliferated from coast to coast. Sports cartoonists like Wallace Goldsmith, Hugh Doyle, Clare Briggs, Burris Jenkins and Gene Mack became familiar names to legions of baseball fans.

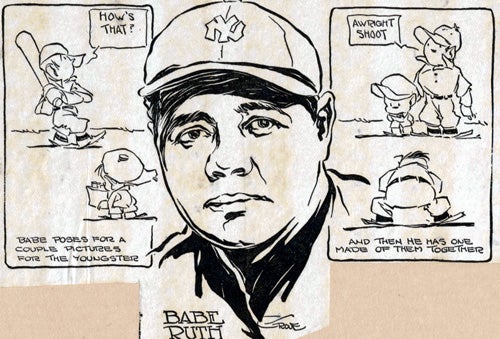

Cartoons were commonly devoted to the game’s star players as well as teams, with Babe Ruth the ultimate subject. Ruth was arguably the first sports figure to become a cultural icon during the mass-media age of the 1920s. Ruth’s infectious charisma and larger-than-life feats propelled him to the level of mythic hero. Subsequently, sportswriters and cartoonists around the country gave immense exposure to Ruth’s prodigious talents.

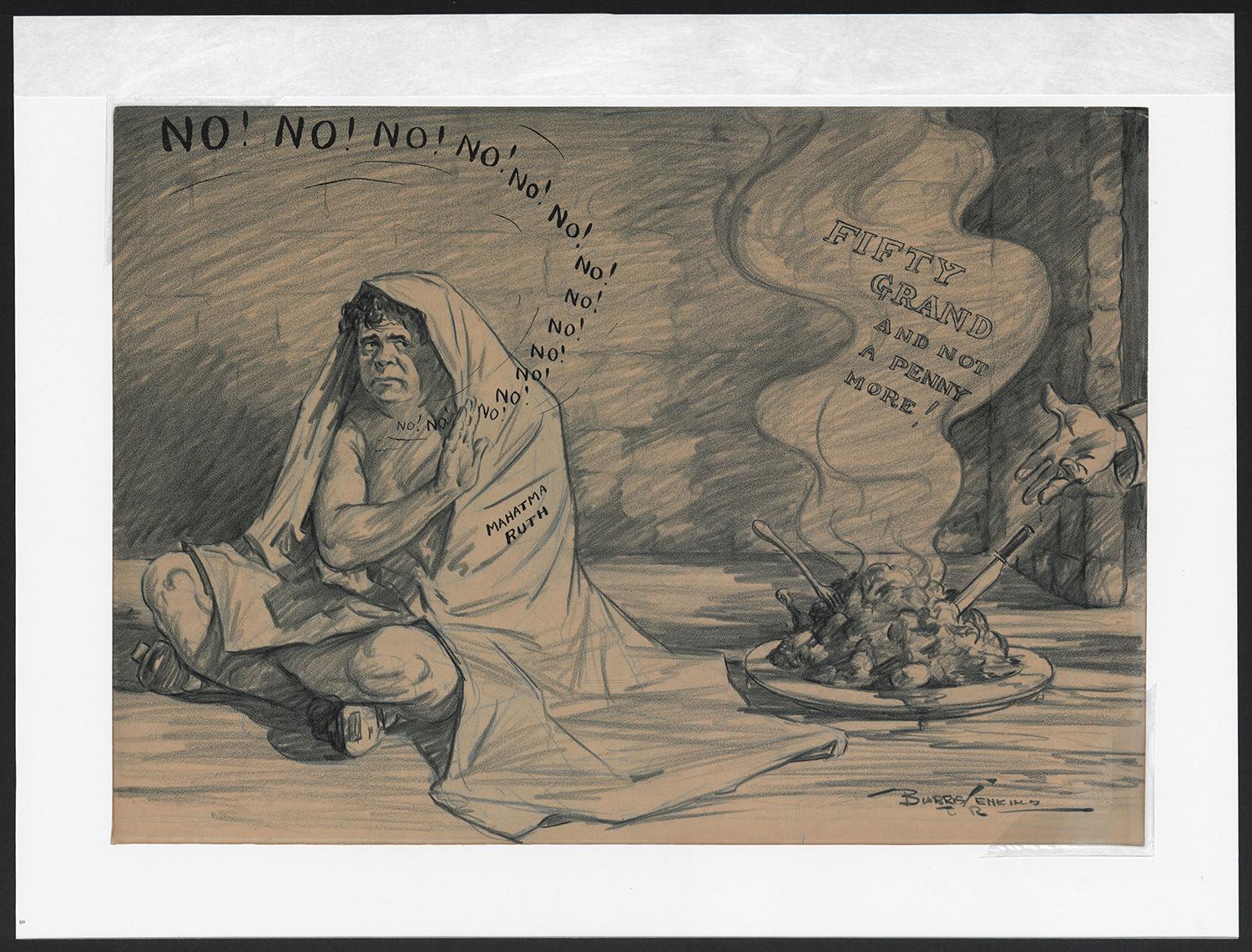

Many such Ruth examples are contained in the Hall of Fame’s collection of original cartoon art (which numbers in the hundreds of pieces). There are a number by famed New York Evening Journal cartoonist Burris Jenkins Jr, including one entitled Mahatma Ruth from March of 1933 which depicts Ruth as Gandhi as he “fasts” in an effort to get the salary he wanted. By 1933, all major league teams were financially strapped due to the economics of the Great Depression. At first Ruth refused to take a pay cut from $75,000 to $50,000, but he eventually signed for $52,000.

Another Jenkins cartoon entitled The Hand That Fed Them! depicts Ruth being chased by a pack of dogs printed in May of 1935. After the Yankees refused Ruth a managing job after the 1934 season, he signed with the Boston Braves but played only a couple months before retiring. As a cultural icon, Ruth’s seeming rejection by all levels of the baseball establishment at the end of his playing days became a noteworthy event. As Jenkins was quoted as saying: “A well thought out cartoon can tell the reader the story in a second.”

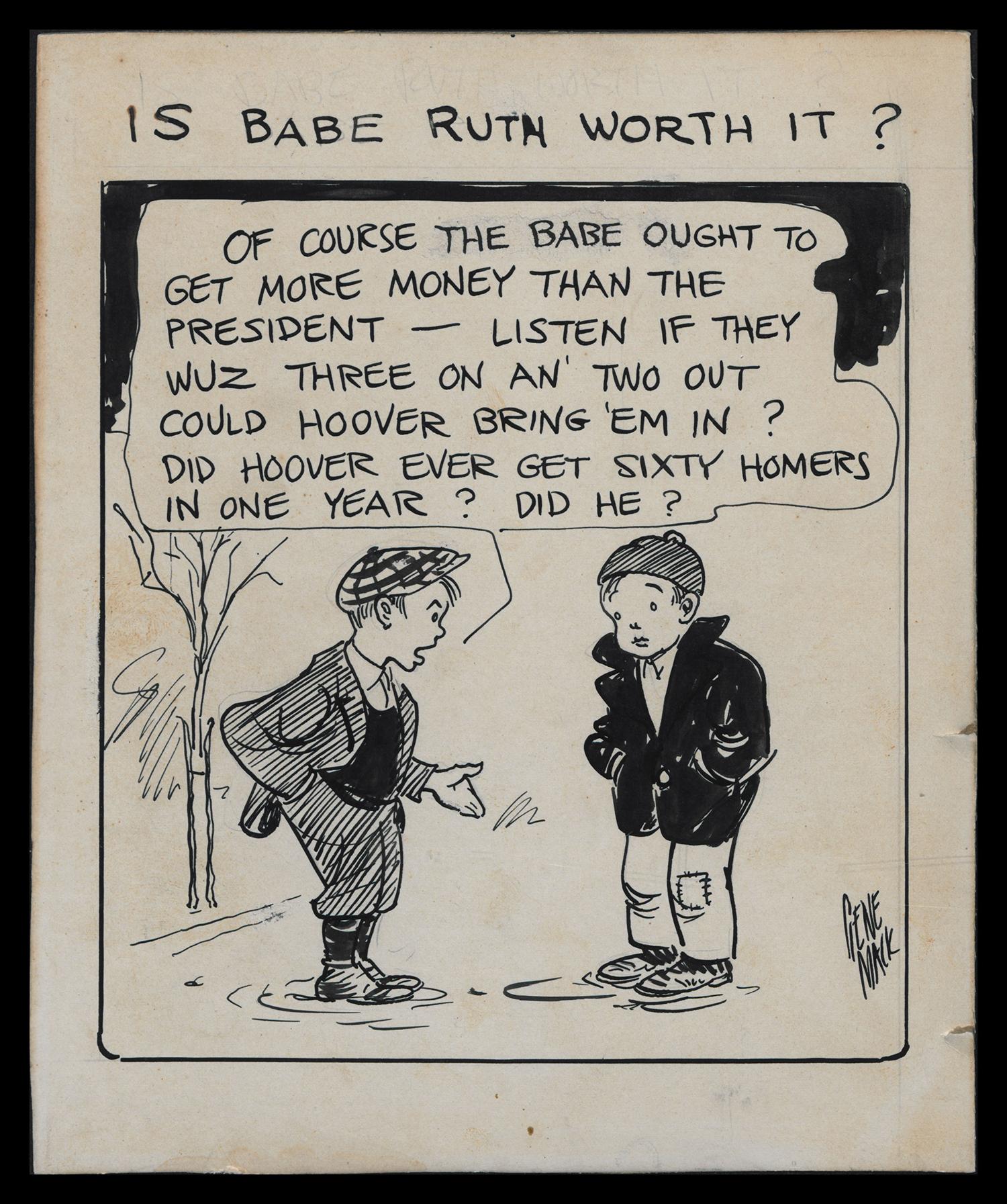

Gene Mack, the famous Boston Globe cartoonist, also often utilized Ruth as a subject. One well known piece entitled Is Babe Ruth Worth It? commented on Ruth’s 1930 salary of a hefty $80,000, five thousand more than that earned by President Herbert Hoover. This was an immense sum of money for the early days of the Great Depression, and it seemed preposterous to some that an entertainer made more than the President of the United States. When asked why he thought he deserved to be paid more than the President, as the story goes, Ruth responded “I know, but I had a better year than Hoover.” Technological innovations such as radio, movie reels, and later, television, spurred baseball’s soaring popularity, whereby spectators far and wide whetted their appetite for news about their favorite ballplayer.

Erik Strohl is the vice president of exhibitions and collections at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

The Voice of Babe Ruth

Babe Ruth clubs his first major league homer

#Shortstops: Waite Hoyt Remembers The Babe

The Voice of Babe Ruth

Babe Ruth clubs his first major league homer