It doesn’t matter how much of a collection you have if you can’t play the tapes or you don’t know what’s on them. It’s just a lot of stuff to look at on a shelf."

- Home

- Our Stories

- Sounds from Silence

Sounds from Silence

Museum’s Digital Archive Project focusing on Collection’s Audio Recordings

Fourteen-thousand hours.

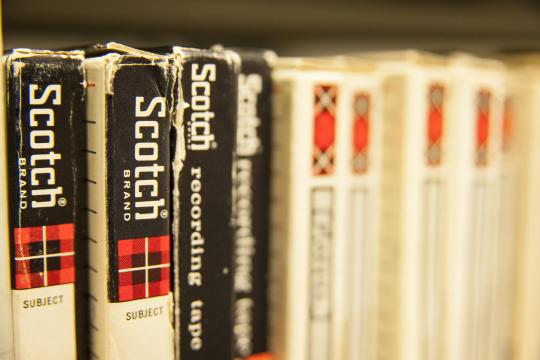

That’s the estimate of how much original recorded media resides in the Library Archive at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. But while the shelves in the Archive represent the largest collection of recorded baseball history anywhere in the world, many of the stories and information held within have remained largely undiscovered.

The Museum’s audio collection – featuring interviews, oral histories, game broadcasts and more – consists of many different types of media including reel-to-reel tapes, cassettes and microcassettes, 45 rpm vinyl records and even aluminum records. These pieces are preserved in climate-controlled conditions in Cooperstown, but if no one is able to hear what’s on them, their full historical value remains untapped.

As technology evolves, these forms of media run the risk of being left behind. Each passing year makes it more essential to preserve these recordings to ensure they can be enjoyed by future generations.

So, the problem for the Hall of Fame became this: How could it find the right machines and, more importantly, the right people who could conserve and digitize these valuable pieces of history?

Luckily for the Museum, the answer was found just two-and-a-half hours down the road from Cooperstown.

“Welcome to the hole,” laughed David Schwartz as he welcomed Hall of Fame staff members into his house in Newburgh, N.Y. Together with his wife, Donna, Schwartz is the co-owner of DDS Enterprises-Information Alchemy, an audio restoration company. The husband-and-wife team operate DDS from the comforts of their home, a former optometrist’s office that has been converted in a working museum of sorts for the two passionate audiophiles.

Greeted at the door by six tape duplicators – some of the few remaining of its kind, whose size resembles industrial washing machines – the visiting team from Cooperstown took a step back in time. Each of the succeeding rooms contained more relics – walls of tape decks, shelves of old reels and CDs, sound boards and even an old Macintosh II – that David affectionately refers to as the couple’s “Island of Misfit Toys.”

But the Schwartzes have a history that lined up perfectly with the Hall of Fame’s needs. David had been an audio engineer for many years in New York City, serving as director of engineering for Inner City Broadcasting (WBLS-FM/WLIB-AM) and helping to build new WCBS-FM studios in the MTV building in Times Square.

Along the way, he took in these “outdated” machines that were about to be thrown away.

“They would ask me, ‘Do you want all this equipment?” Schwartz laughs, “I was young and stupid, so I said yes.”

Then in the mid-1980s,the assets of renowned recording studio Barclay Crocker Company of Poughkeepsie, N.Y., went up for sale. Along with the equipment, David & Donna brought home the company’s production master tapes. Sensing once again that these valuable pieces would otherwise be destroyed or neglected if they didn’t find a home, David and Donna sought to preserve the collection. But they soon noticed an issue when they put the tapes on a machine.

“We tried to play the tapes and we found they wouldn’t play properly,” David said. “So we had to start researching why they wouldn’t play.”

Unintentionally, the Schwartzes had created a project and, subsequently, a business for themselves. In 1986, they founded DDS Enterprises and formed a powerhouse team. David’s specialty lies in the technical aspects, while Donna, a journalist, handles the information tasks of tracking and cataloging.

Together, the couple is in lockstep with a common goal of preserving the cleanest sound, extracting the most information and conserving original recordings for optimal chances of survival.

“When we do a restoration process,” said Donna, “we have the expectation that these are going to be the definitive copies that are going to be the historical record.”

By 2013, DDS had large-scale projects for the Loyola Baltimore Jazz Society and CBS Radio (in which it handled somewhere between 5,000-8,000 reels of tape) on its resume. That’s when David received a phone call from a friend who was an employee at the EMC Corporation, who informed him that EMC had given a grant to the Hall of Fame so it could begin digitizing its vast collection.

“I thought wow, that’s an amazing project,” David recalled, “I’d like to be in on that.”

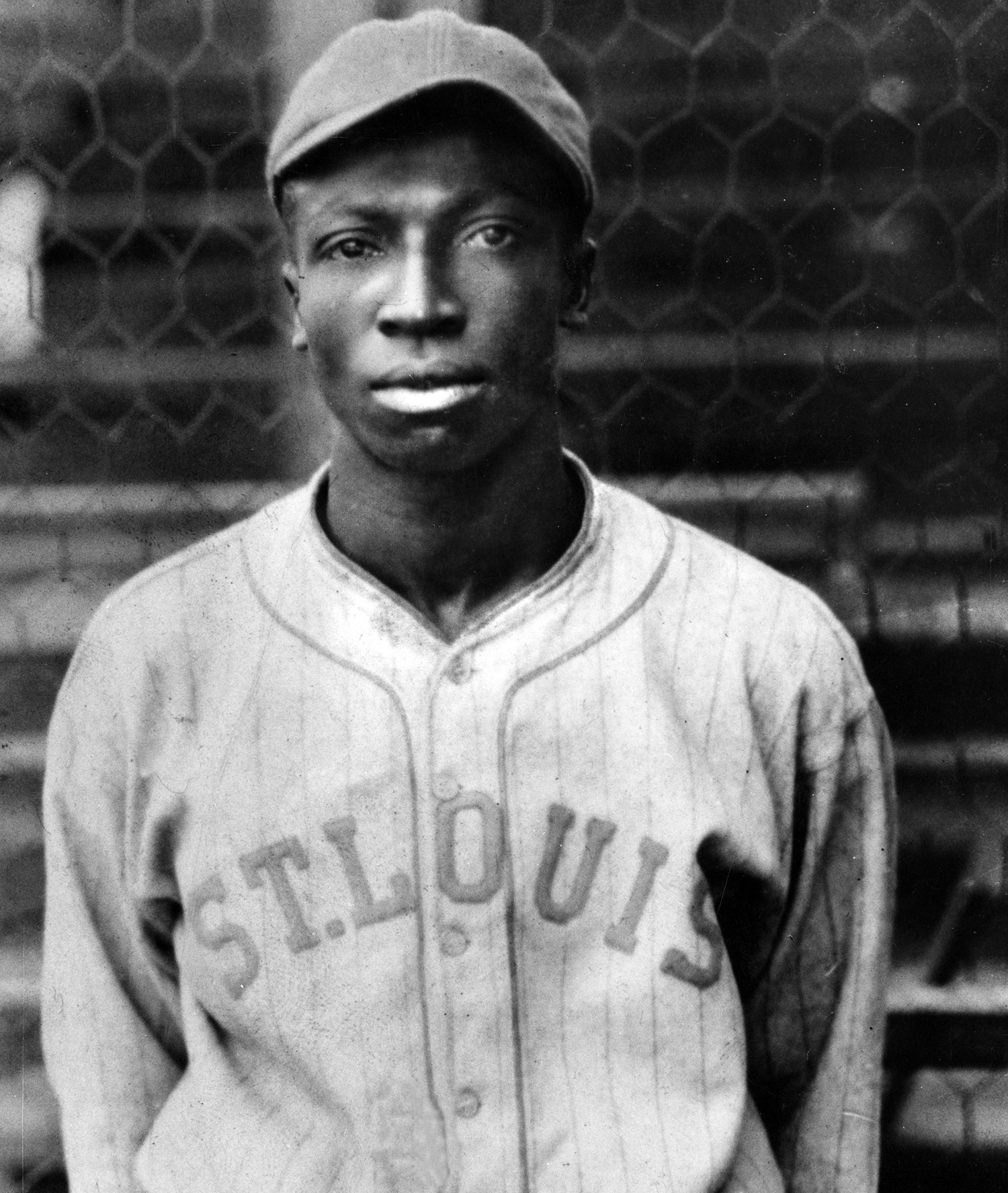

The couple introduced themselves to staff in the Hall of Fame Library, who sent them a sample of recordings to work on in 2015. The first batch included interviews with Emmett Ashford, the major leagues’ first African-American umpire, and Negro League legend and Hall of Famer Cool Papa Bell.

“It was a thrill to hear these pioneers – in their own voices – talk about their motivations and share their anecdotes,” Donna said. “This isn’t stuff you see in the movies; this is raw and real.”

While the Hall does its best to halt the deterioration process in dehumidified, climate-controlled spaces, the reality is that these physical recordings are still degrading. Tapes will adhere moisture wherever they can. Aluminum records, originally intended to be souvenirs, will only play a few times before losing their utility. This physical erosion creates a need for digitization, and it also dictates that DDS thoroughly inspect and diagnose these relics before they go anywhere near a recording device.

“If any material comes off of the tape – if any shedding occurs or if the substrate sticks to the tape ahead of it – that material is lost and there is no way to retrieve it,” Donna said. So she and David unwound each tape and meticulously inspected it for splices and other potential snags. Then the tapes were “baked”, or dehydrated, for anywhere from eight to 24 hours to ensure they are free of any and all moisture.

Once the tapes were dry it was time to place them on the decks for playback and digital recording. But another problem arose: The original copies may have been recorded on devices whose reel heads were worn or off-kilter machines. There’s a risk of damaging the tape or not producing the right sound if the devices don’t mimic the original configuration.

“We hook the reel up to an oscilloscope that helps us maximize the peaks,” David explains, “so even if we have to adjust our tape heads to be slightly off-kilter to match that tape head, then we get the maximum sound fidelity level that we can out of it.”

Once the machines were aligned, the reels and cassettes were run through a digital-to-analog converter that creates a hi-fi 96k/32-bit archived copy that would join the original back in the Library Archive in Cooperstown. If better digital technology arrives in the future, this archived copy could be used instead of hoping that the original reel is still functional by that time.

With physical duplication complete, the process moved on to digitizing the recorded audio. Digitization, however, entails more than simply uploading a massive mp3 file. The first step is creating maximum fidelity – “listenability,” in other words – by removing hisses, pops and other distracting sounds. But the Schwartzes insist a fine balance must be struck between enhancing the sound while preserving its original ethos. The listener should still feel like they’re being transported back to the settings where the recordings took place.

“We use a combination of everything we’ve got in our arsenal for whatever the tapes need – and every one is different,” David said. “Getting a good sounding copy without dramatically altering the sound of the original, that’s the key. You should never go too far with that.”

“The important thing is to preserve the person’s voice as they speak,” Donna added. “You don’t want them to sound like James Earl Jones or Morgan Freeman reading a transcript of the interview. You want to hear their thoughts, their recollections and their opinions in their own voice.”

Once they were satisfied with the sound quality, Donna began tracking and cataloging each recording. Given the length of many of these interviews – the discussion with Cool Papa Bell totals roughly seven hours, for instance – these steps prove essential for several reasons.

“You could look at a data sheet and say, ‘Cool, we’ve got stuff from Cool Papa Bell,’” said Donna, “but what is he talking about? You want to have this accessible and available to people, and in order to do that you have to know what’s available in those seven hours.”

Donna broke the recordings into searchable tracks that made these massive sound files much easier for the Hall of Fame to digest and share with its audience. One track from the Papa Bell recording, for instance, features the speedster speculating his chances in a footrace against Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens. Another features the intriguing label, “Burying Money in a Jar in the Backyard.”

“It’s fantastic to think about a student at some point in the future doing a report on Satchel Paige,” Donna said, “and having the ability to go online and search these recordings and hear Cool Papa Bell say, ‘This guy was able to hit a matchbox with a pitch.’ I mean, that’s a fantastic story!”

Finally, the reels and cassettes were library wound and returned to Cooperstown “in at least as good a shape as we got them, if not possibly in a little better,” David said. The Ashford and Bell interviews can now be preserved both physically and digitally at the Hall of Fame, but they represent just the tip of the iceberg. The Museum hopes to digitize many more of these recordings as part of its Digital Archive Project, but ongoing efforts will be expensive in terms of both time and money.

The Museum has agreed to a continued partnership with DDS Enterprises, who will digitize and restore all of the various audio formats in the archives over the course of the project.

The intrinsic value, however, of discovering and preserving these interviews, stories and information will prove to be priceless.

“A lot of this archival material may not have been heard by anybody,” said David Schwartz, “and it doesn’t matter how much of a collection you have if you can’t play the tapes or you don’t know what’s on them. It’s just a lot of stuff to look at on a shelf.”

“We’re doing this because we love it,” added Donna. “We take our role as conservators very seriously, and we believe that we’re putting out something that is an important part of our history and will be sustained into the future.

“You cannot put a price tag on some of the material we’re working with, because if we’re not working with it and doing it correctly it could disappear. We love the material, and we love working with people who care about preserving history.”

Matt Kelly was the Communications Specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum