- Home

- Our Stories

- Ted’s pursuit of .400

Ted’s pursuit of .400

Though it had been only 11 years since a baseball player had ended a season having hit .400, it was still newsworthy when a young Ted Williams flirted with the magical mark 75 years ago.

By early June 1941, after a May in which he hit .436 (44-for-101), newspapers across the United States were already trumpeting the batting prowess of the 22-year-old Williams. The long and lean “Kid,” all 6-foot-3 and 175 pounds of him, was using his left-handed swing with the amazing wrist action to hit in the .430s.

“It’s a dream I’ve always had – the way I’m hitting now,” said the Boston Red Sox left fielder, batting .436 at the time, in a June 7, 1941 interview with The Boston Globe.

“Boy, I’m just busting the cover off that ball. I’m lucky because a lot of my drives are going where they ain’t. And hell, it’s only June. I may be down to .360 in another month.”

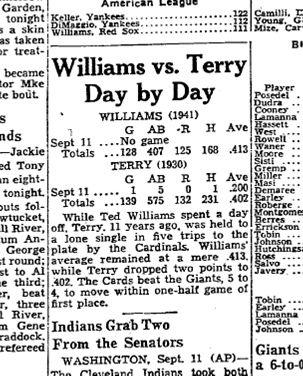

The Boston Globe, due to the nationwide interest in Ted Williams' chase for .400, started a new daily feature that would compare the daily doings and aggregate totals of the Red Sox slugger that season with those of Bill Terry of the New York Giants on the corresponding date in 1930. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Having exploded on the big league baseball scene as a rookie in 1939, hitting .327 with an American League-best 145 RBI, then following it up in ’40 by batting .344, Williams admitted that his approach at the plate hadn’t changed at all in 1941, remarking “it’s the same old bat, same old swing and same old Kid.”

By mid-July 1941, with a batting average hovering in the .390s, the player the newspapers were calling the “Boston string bean,” “Toothpick Ted,” the “Willowy Walloper” and the “Boston beanpole” still had his doubts about hitting .400.

“Say, 400 is some batting,” Williams said. “Look how many hitters have done it in the history of the game … not very many. The odds against me are at least 20 to 1 … maybe 50 to 1.”

Up until that point, a little more than two dozen big league ballplayers over the years had ended a season by batting .400 with the minimum required plate appearances. Bill Terry was the last player in either major league to accomplish the rare feat, hitting .401 for the 1930 New York Giants. Harry Heilmann was the last American Leaguer to join the ranks when he batted .403 for the Detroit Tigers in 1923.

The Boston Globe, due to the nationwide interest in Williams’ .400 batting attempt, announced on July 30, 1941, that they would be starting a new daily feature that would compare the daily doings and aggregate totals of the Red Sox slugger that season with those of Terry compiled on the corresponding date in 1930.

The Globe’s headlines soon enough reflected the city’s fascination with their young star’s chase of one of the game’s magic numbers: “Ted Williams Far Above .400 in Kindly League”; “Ted Lifts Hit Mark to .410 Before 22,577 Sox Fans”; “Ted Lifts Average to .413 as Sox Bow.”

Despite his hitting prowess, Williams sometimes was less than stellar on defense.

“Oh, hell,” said Williams, complaining in an Aug. 8, 1941 Associated Press article on the day after a game in which he was given an error by the official scorer. “I don’t give a damn about fielding anyway. They say I’m a bonehead fielder and maybe they’re right. But, Bud, I’m a hitter. I can bust ‘em.”

On Aug. 11, 1941, the Washington Post printed a column by Shirley Povich in which the future Ford C. Frick Award honoree interviewed Hall of Famer Hugh Duffy about Williams’ pursuit of .400. The former outfielder, then 74 years old, set the big league single-season record when he batted .440 (then thought to be .438) in 1894 with the Boston Beaneaters.

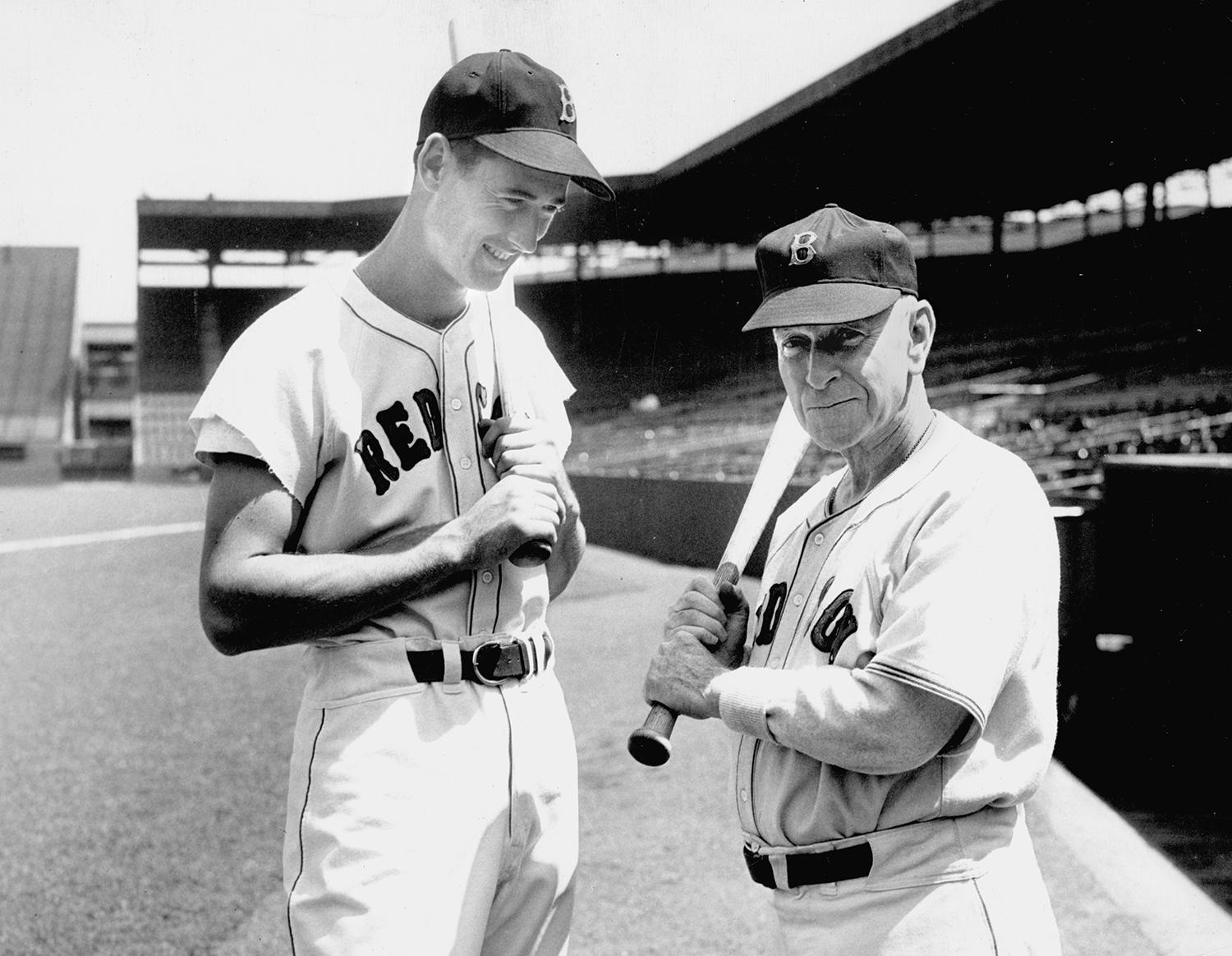

Hugh Duffy (right), who set the record for the highest batting average in a single season with .440, told Shirley Povich of the Washington Post, that "until Williams came along, I thought my record was safe forever...I didn’t think anybody would come close, but now this Williams comes along and I don’t think it’s out of his reach." (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

“Until Williams came along, I thought my record was safe forever,” Duffy said. “For more than 30 years I virtually forgot about it. Folks weren’t so excited about batting averages those days. They didn’t make so much fuss over ‘em. Then when [Rogers] Hornsby came along in 1924 and hit .424 they started checking up on the old records and there mine was.

“Then I began to take some pride in my .438 and of course I was kind of glad that Hornsby didn’t outdo it. When he failed I thought it was safe for all time because Hornsby was just about the greatest of the modern-day hitters,” added Duffy, who as a Red Sox employee had seen Williams play more than 200 games from the Fenway Park press box. “I didn’t think anybody would come close, but now this Williams comes along and I don’t think it’s out of his reach.

“Sure I will,” said a confidant Williams about hitting .400 in an Aug. 15, 1941 AP article. “It’s going to be a cinch. All it takes is luck, confidence and good hitting – and boy I’ve got all three.

“You’ve gotta have luck. I’ve had it all year – my longest hitless stretch was eight times at bat – and I think I’ll keep on being lucky. And I’ve got my share of confidence. Every time I go up to bat I feel like a million dollars. When a curveball comes down at me – wham! I lay into it. Of course, luck isn’t everything. You have to be a reasonably good hitter, too.”

“I’ve never seen a better hitter. He’s got everything to hit with. A great bead on the ball, the courage to stand up there, and the best arms and wrists I ever did see. The amazing thing is he’s mostly a pull hitter. He gets a lot of home runs and extra-base hits that way, but the high-average hitters are usually the fellows who hit straight-away where there is more room for hits. That’s where I made most of my hits, toward center field.”

Starting in late July 1941, Williams’ batting average that season would never dip below .400.

When asked if he was ever nervous trying to keep a .400 batting average, Williams exclaimed, “Nerves! I don’t know what they are. I know I can hit and I never think about keeping over .400. I just take my cut at the ball and let the nerves take care of themselves. Here’s the way I look at it. If I hit .400 this year everyone’ll say I’m great. Then if I do slip to .200 next season, everyone will holler, ‘He’s just a flash in the pan.’ But I’ll tell you one thing. There’ll always be one guy who believes Williams can hit – that’s old Ted himself.”

It wasn’t completely smooth sailing for Williams in 1941, as he had chipped a bone in his right ankle in Spring Training then reinjured the ankle sliding back into first base in Boston’s first game after the All-Star Game, a contest in which he hit a walk-off three-run homer with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning off Claude Passeau to give the Junior Circuit a 7-5 victory.

In mid-August 1941, Joe DiMaggio, the New York Yankees center fielder who famously set a major league record by getting a hit in 56 straight games in a streak that ended on July 17 that season, was asked about overtaking Williams for that year’s batting crown.

“Ted Williams is in a class by himself this season,” said DiMaggio, quoted in an Aug. 19, 1941 New York Post article. “I’ve given up all hope of catching him now. What’s the point of kidding myself? I’ve no more chance of doing it than … well, than the rest of the league has of catching up with the Yankees and keeping us from winning the pennant.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Red Sox Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

In an article published in the Sporting News on August 21, 1941, Eddie Doherty, the publicity chief of the Red Sox or Director of Public Information, recalled that Williams once told him that hitting is the most puzzling profession in the world.

“He said, ‘If Mr. Yawkey (Red Sox owner) gave you a list of 10 things to do and you were able to do only four of them, the chances are you’d be bounced out on your ear. Yet, if I, as a hitter, make four hits in 10 tries, I’m a .400 hitter, and a sensation. It doesn’t make sense,’” Doherty said. “When Ted put it that way, I’ll admit it confused me, too. But I decided to say nothing to Mr. Yawkey about it. I’m willing to bat 1.000 in my job, or try to, as long as Ted hits .400 in his. In that way both of us will please Mr. Yawkey.”

Memorably, as the 1941 season came to a close, Williams was hitting .3996 after the penultimate day of the regular season, good enough if he didn’t play in a season-ending double-header against the Philadelphia Athletics to be recognized as a .400 hitter.

Given the option to sit out by his manager, Joe Cronin, Williams, who turned 23 on Aug. 30, instead chose to play and hit 6-for-8 in the two games and finished at his now famous .406, becoming the last batter to reach the milestone .400 mark.

“If there’s ever a ballplayer who deserved to hit .400, it’s Ted,” Cronin said after the double header. “He’s given up plenty of chances to bunt and protect his average in recent weeks. He wouldn’t think of getting out of the lineup to keep his average intact.”

Besides Williams’ .406 batting average – the AL race had Washington’s Cecil Travis finish second at .359 followed by DiMaggio at .357 – he also led the majors in walks (147), on-base percentage (.553), slugging (.735), runs scored (135) and home runs (37). His 120 RBI were fourth in an AL race topped by DiMaggio’s 125.

Most recently, batters who’ve made a run at the .400 mark have included fellow Hall of Famers Tony Gwynn, who batted .394 in 1994, George Brett, who batted .390 in 1980, and Rod Carew, who batted .388 in 1977.

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Museum Partners with Artist Bill Purdom for 75th Anniversary Artwork

Hall call thrilled Raines, Rodríguez and Bagwell

1985 Hall of Fame Game

Steady Ted Lyons thrived as White Sox ace

Time to PLAY Ball

He Called It

BL-175.2003, Folder 1, Corr_1971_02_14