- Home

- Our Stories

- Can’t Beat that Job

Can’t Beat that Job

It was a kinder, gentler time when I began writing baseball in St. Louis in the 1970s.

There was no internet. There was no ESPN. There was no sports talk radio. There were just newspapers – only two of them publications that traveled with the team – the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

But the Globe died, was revived and then died again, and suddenly in the mid-1980s, there was just one newspaper. ESPN had just started, sports talk radio hadn't made any real in-roads and there was still no internet. Blogging was a term that hadn't even made it to Webster's yet.

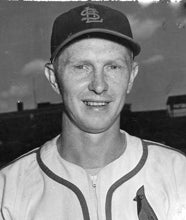

And not only was there just one major paper in the area, this baseball writer covered a manager who loved newspapers at the expense of radio or television. Hall of Famer Whitey Herzog, who managed the Cardinals from 1980-90 and into three World Series, was a baseball writer's dream.

In fact, he often said: "I want to see in the newspaper the next morning something I said that they didn't have on TV or radio the night before."

Herzog would hold court with the writers at almost any time they wanted. During the 1987 World Series for instance, to assist reporters with their off-day stories between the Minneapolis and St. Louis venues, Herzog, on request, appeared at a St. Louis downtown saloon, the Missouri Bar and Grille, and conducted a press conference there for a fistful of scribes.

The manager was well aware that the visiting (and home) scribes used to make the Grille their postgame headquarters. Herzog said: "The first day of a series, the writers would come in here and ask a bunch of questions and then they'd go out with Hummel to the Grille. The next day, after they'd gone out with him again, they'd come in and they wouldn't be looking too good and wouldn't be asking as many questions. The third day, they'd come in looking terrible and I ended up asking all the questions."

And he usually had all the answers.

My mentor, 1979 BBWAA Career Excellence Award winner Bob Broeg, had helped to impress on me how important it was to go to the manger's office early in the afternoon and get a feel for that night's game or just to touch base on previous items. On many occasions, I would have a discussion with Herzog while he was completing the charts that his starting pitcher for that night had filled out covering the previous day's game.

Before the computer age, I was intrigued at how Herzog had a different color pencil for each of his pitchers, and his hitting charts would be just as extensive. Across from his desk, he had a large file cabinet, covering active players and pitchers and even something he called a "dead file," for those no longer playing. Formerly with Texas, California and Kansas City as a manager before he arrived in St. Louis, Herzog had been tabulating this information for so long that one day, after pulling open one drawer, he said: "Hmm… Some of these guys actually are dead."

The best part about covering Herzog and the Cardinals in those days was that you often had him to yourself before a game – especially on the road – and for as long as you needed. He rarely seemed as if he was in a hurry to terminate the pre-game conversations.

Post-game conversations with Herzog also were productive, more so, strangely, when his team had lost or played poorly. He wasn't afraid to name names. Whatever the outcome, he always took care of the newspapermen first, and then took on the cameras and microphones, reluctantly.

The best part about covering Herzog and the Cardinals in those days was that you often had him to yourself before a game – especially on the road – and for as long as you needed. He rarely seemed as if he was in a hurry to terminate the pre-game conversations.

Post-game conversations with Herzog also were productive, more so, strangely, when his team had lost or played poorly. He wasn't afraid to name names. Whatever the outcome, he always took care of the newspapermen first, and then took on the cameras and microphones, reluctantly.

On one hot Sunday afternoon in August, Herzog beseeched this reporter before the game to ask as many questions as possible afterward because it being a day game, there would be more cameras and microphones in his office and he didn't really want to deal with them.

After this game, I asked fully 45 minutes worth of questions before I absolutely had none of any import left and noticed that one man from a TV station about 200 miles away was barely able to hold up his camera anymore. Herzog then winked at me and my day was done.

When the Post-Dispatch was an afternoon paper, I often traveled on the team airplane (the paper was billed later) and then wrote my story in the next city. But after the P-D went to a morning publication upon the final demise of the Globe-Democrat, I traveled for a couple of years more on the team plane, sometimes rushing to finish my story for the next morning in the 45-minute window I had before the team bus left the clubhouse.

If I didn't make the deadline for the bus, I would hop a cab and get to the airport where an airline aide would then whisk me to the plane. Imagine trying to do that now? If I was running late, but not too late, Herzog and the airlines would invent some minor mechanical issue that had to be dealt with, such as the stairway to the plane having a step that creaked, or something trivial like that. Herzog would always wait for me, but, when mercurial pitcher Joaquin Andujar strayed from the reservation in New York and was not going to be on time for liftoff, he had the plane take off without Andujar.

There was no question that I had the most fun in my career covering the Cardinals teams of the 1980s under Herzog. They were successful and he was accessible.

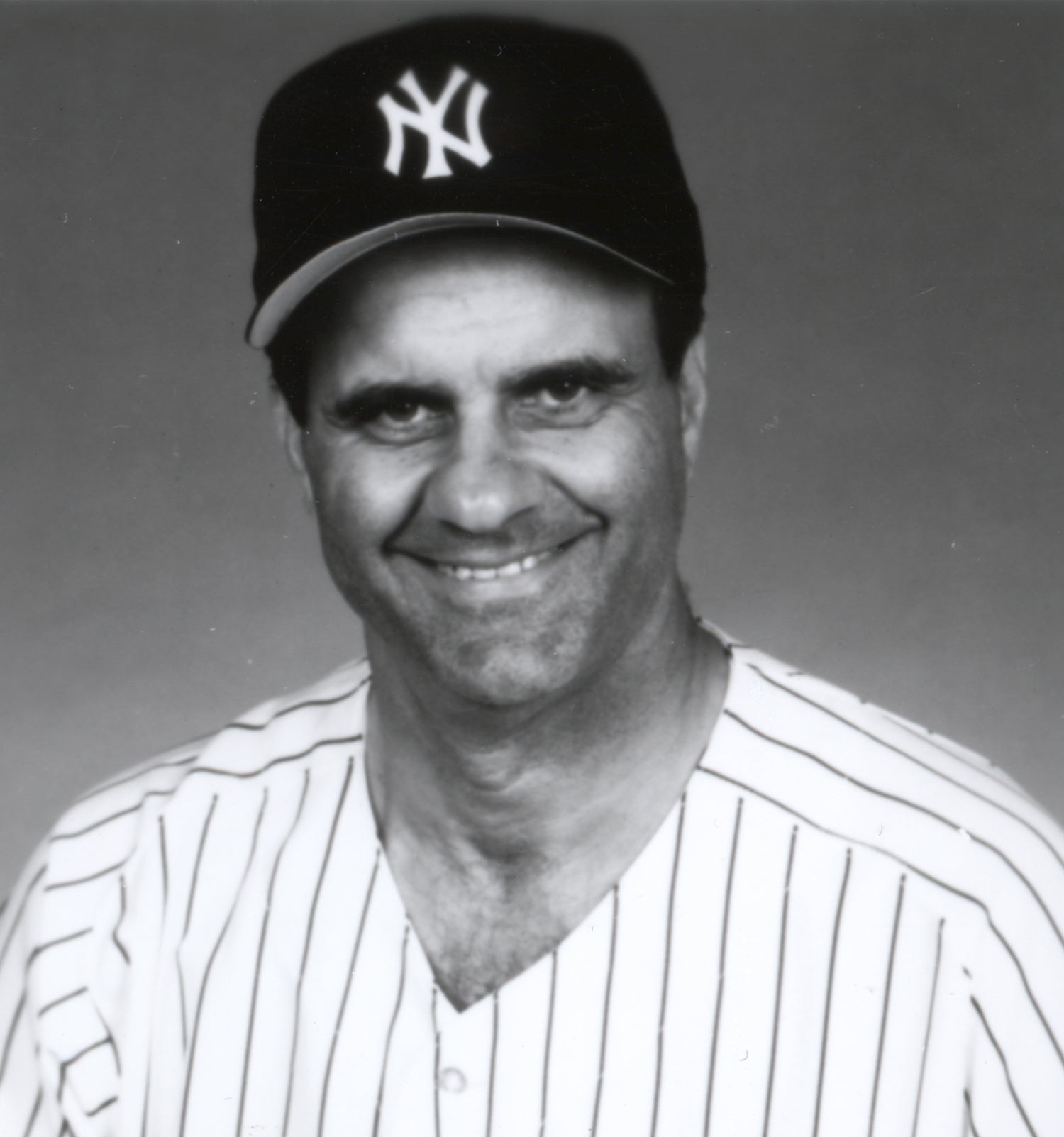

But I've been blessed in my nearly 40 years of covering baseball to have covered basically only four managers: Red Schoendienst, Herzog, Joe Torre and Tony La Russa. All are considered at the top of their craft and they all taught me a lot about what to watch for in a baseball game and how to deal with people.

Red and Whitey grew up in the St. Louis area, so they know the passion St. Louisans have for the Cardinals. Torre played with the Cardinals, so he knew, too. And La Russa, though mostly a career American Leaguer until he arrived in St. Louis, didn't take long to understand what it means to manage there.

Torre especially seems comfortable dealing with all manner of media that are around the ballpark now and La Russa, who doesn't seem to enjoy it quite as much, still knows multimedia is the order of the day.

Even Herzog, in retirement, does more radio and television than he ever did when he managed.

As far as the Cardinals players are concerned, the veterans have always made it easier for me to cover the team by telling the new players that I was nicknamed the "Commish," whether they knew why or not.

While St. Louis isn't a big enough city where you should be overwhelmed by the various types of media, it is often an annoyance to an old-school writer to have to traverse his way through a maze of cameras and microphones.

St. Louis has an abundance of sports talk radio, mostly centering on the Cardinals. So there almost never is a day when you can walk into the manager's office and sit there and talk to the manager by yourself.

On the other hand, being a baseball writer, particularly in St. Louis, is better than having a real job. I just wish I still had my old Olivetti typewritter.

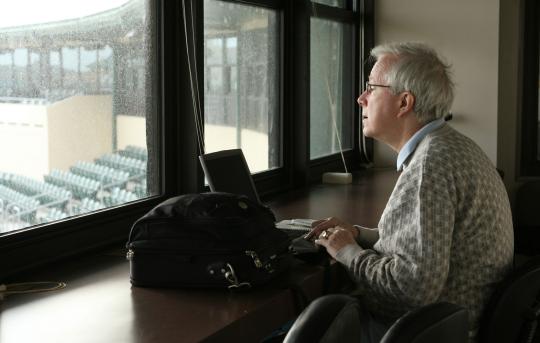

Rick Hummel covers the St. Louis Cardinals for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. In 2006, he won the BBWAA Career Excellence Award for excellence in baseball writing